Are recessions about employment?

I’d say yes, but Nick Rowe disagrees. He recently tweeted an old post from 2015, which ends as follows:

Recessions are not about output and employment and saving and investment and borrowing and lending and interest rates and time and uncertainty. The only essential things are a decline in monetary exchange caused by an excess demand for the medium of exchange. Everything else is just embroidery.

First I’m going to tell you why I disagree, and then I’ll explain why my disagreement is not very important, at least for the US economy.

I don’t believe that terms like “monetary exchange” and “excess demand” are clearly defined. In my view, the most useful definition of a recession is a slowdown in employment growth that is sudden, significant and in some sense “anomalous”. By that I mean a slowdown in employment growth that seems unrelated to fundamental factors such as demographics or preferences.

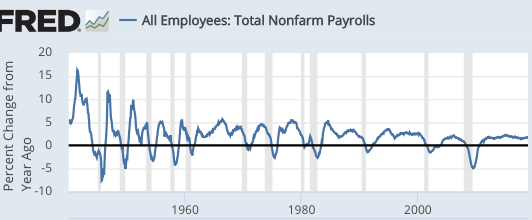

As this graph shows, slowdowns in employment growth are extremely strongly correlated with “recessions”, as defined by the NBER. (The end of WWII was a bit weird. But that was an unusual period, with women entering the labor force during the war, then leaving, and soldiers returning home.)

Thus in an accounting sense, recessions are mostly about employment, not factors such as productivity. And most economists believe the reduction in employment during recessions is non-optimal, that it does not reflect preferences. So what causes this slowdown?

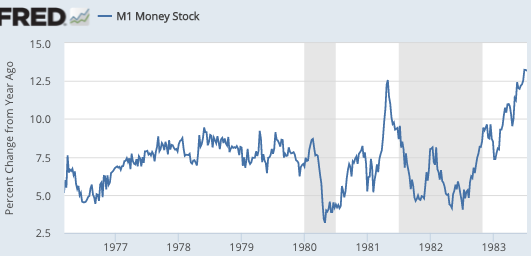

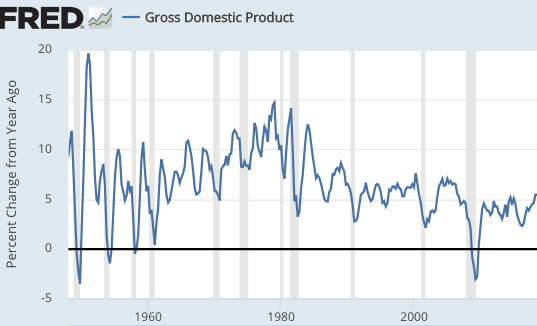

In my view (and I think Nick agrees), these recessions are caused by sharp declines in NGDP growth in an economy with sticky wages and prices. Here is some data on NGDP growth:

Once again, the correlation is quite strong. At the same time, I could easily imagine other factors causing a recession. A government might institute an extremely high minimum wage rate, and then later remove this wage floor. This would temporarily depress employment growth, without impacting NGDP. So I don’t see how recessions can always be caused by an excess demand for money, unless they are defined that way. But since we cannot directly measure excess money demand, that’s not a useful definition. All we can do is look at various macro variables and infer that there was an excess demand for money.

Once again, the correlation is quite strong. At the same time, I could easily imagine other factors causing a recession. A government might institute an extremely high minimum wage rate, and then later remove this wage floor. This would temporarily depress employment growth, without impacting NGDP. So I don’t see how recessions can always be caused by an excess demand for money, unless they are defined that way. But since we cannot directly measure excess money demand, that’s not a useful definition. All we can do is look at various macro variables and infer that there was an excess demand for money.

Nor can we solve the problem by looking at the other part of Nick’s definition, a “decline in monetary exchange”. If monetary exchange suddenly falls in half, and all wages and prices are cut in half by administrative fiat, there may not be a recession. Indeed something like this occurs during a currency reform.

[Please don’t misinterpret this observation. I am not claiming that making wages and prices flexible is a good way of avoiding recessions, it isn’t. Rather the thought experiment shows that a recession is not identical to a decline in monetary exchange. And keep in mind that NGDP is only a tiny fraction of “monetary exchange”, which is dominated by the exchange of money in the financial markets.]

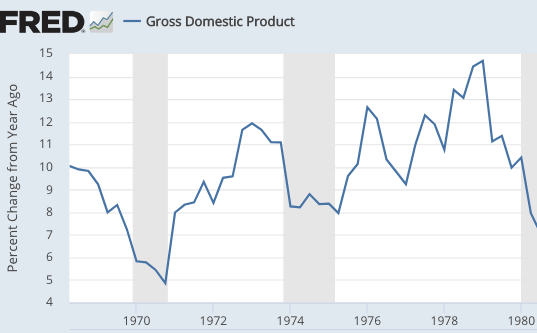

Let’s look at the recession that is generally regarded as the least monetary of all post-WWII US recessions, November 1973 to March 1975:

That graph is actually pretty good for Nick’s claim, as even the least monetary of all recessions looks quite monetary. NGDP growth slowed significantly during the 1974 recession.

That graph is actually pretty good for Nick’s claim, as even the least monetary of all recessions looks quite monetary. NGDP growth slowed significantly during the 1974 recession.

On closer inspection, we can see why this is viewed as the least monetary recession. The slowdown in NGDP growth was fairly mild compared to other recessions, whereas the fall in employment growth and RGDP was relatively severe, at least for the post-1965 period.

Many economists would attribute this to 1974 being an adverse “supply shock”, caused by soaring oil prices. I’m not so sure, as the equally severe 1979-80 oil shock produced a boringly normal recession; that double-dip recession was about as severe as one would expect from the size of the NGDP growth slowdown in early 1980, and then again in 1981-82. So even that double-dip “oil shock” recession looks quite monetary.

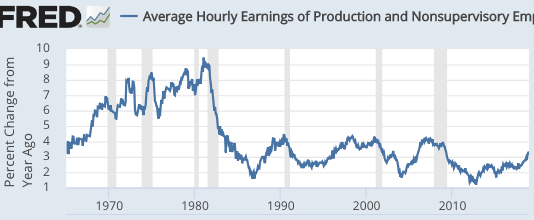

Instead, I believe the unusual severity of the 1974 recession reflects a “wage shock” caused by the removal of wage controls. These same controls had artificially boosted output during 1972 (when Nixon just happened to be running for re-election), and we paid the price in 1974 (when Nixon was fittingly removed from office.) As a result, wage growth actually rose during the 1974 recession.

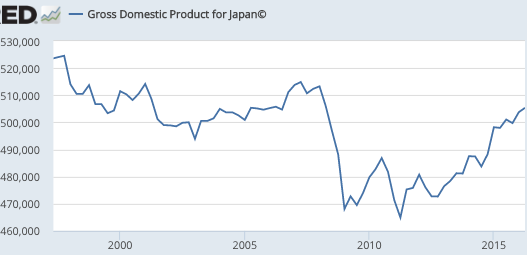

Rather than define a recession as a negative monetary shock that causes less monetary exchange, I’d rather say that a recession is a sudden, sizable, and anomalous slowdown in employment growth. And then I’d say that US recessions are virtually always caused by monetary shocks that reduce NGDP growth, but in other countries (such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe) recessions are often caused by real shocks–usually bad (interventionist) government policies.

PS. I understand that the correlation between NGDP and recessions doesn’t prove causation, but we have a mountain of other evidence suggesting that causation goes from monetary variables such as NGDP to employment.