Last reply to Matt Bruenig

Matt seems to have forgotten to take his meds, as his newest post is one of the silliest I’ve ever read. Here’s an example:

War On Poverty Backtrack

You’ll recall Grandpa Sumner’s initial argument for why transfers don’t net reduce poverty went like this:

-

Since the War On Poverty started, poverty hasn’t fallen at all. I know this because aint that what them dat gum progressive bloggers say?

-

Because poverty hasn’t declined, then that means anti-poverty transfer incomes only crowd out market incomes. Else, you would have seen poverty decline.

-

Therefore transfers don’t reduce poverty.

I was surprised to read this, because I believe exactly the opposite, that poverty has declined, and that transfers have reduced poverty, especially among the elderly.

So I looked for the passages where I made those claims, and all I could find is this:

In fact, we spent trillions on the War on Poverty. Unfortunately, poverty won and we lost. Don’t believe me? Isn’t the blogosphere full of progressives complaining that the poverty rate is just as high as in 1967? I’m actually more optimistic about the living standards of most poor people than the typical progressive. Their living standards have risen with the general population. But if “non-market income” actually explains the gains made by the poor, then this suggests that non-market incomes have merely crowded out market incomes.

It’s absurd to claim that it’s “easy” to solve a problem like poverty. Yes, it’s easy if you are dealing with a group of people for whom you don’t have to worry about work disincentives. Obviously it’s easier to reduce poverty for the elderly, since they are mostly retired. Nixon did that. That would also be true of the disabled, if we could accurately measure disability. (The fact that we cannot partly explains the huge surge in disability, even as Americans are healthier than ever before.)

I guess Matt doesn’t understand sarcasm, or the phrase: “I’m actually more optimistic about the living standards of most poor people than the typical progressive. Their living standards have risen with the general population.” Or “Nixon did that.” Nor has he read my post entitled “The Amazing Decline in American Poverty.” I presume he didn’t understand the sarcasm in the last sentence of my first paragraph, which in context was referring to what must be true if the progressive claim about no decline in poverty since the late 1960s were true. Then I found this:

Again and again, he has called wealth inequality data “nonsense on stilts” because it ignores the fact that wealth inequality is just a life-cycle phenomenon.

Did I really say it was just a life cycle phenomenon? Only a fool would believe such a thing. Wealth inequality reflects many factors. I searched and searched and could not find where I had said that. Matt didn’t help me, as he linked to posts that did NOT say that. Conclusion; Matt just made it up.

And here he goes again:

It would be manifestly bizarre for progressives to have ever bombarded Grandpa Sumner with the argument that poverty fell rapidly from 1922 to 1967 because Mollie Orshanksy didn’t come up with the U.S. poverty metric until 1964, and the Current Population Survey’s good poverty data doesn’t stretch back further than 1967. There is a reason that magic year keeps coming up. In his senility (or motivated desire to manufacture nonsense), Sumner appears to be mixing up claims people make about middle-class incomes and claims people make about poverty. But who knows.

I guess the National Poverty Center at the University of Michigan is just as senile as Grandpa Sumner. This is from their web site:

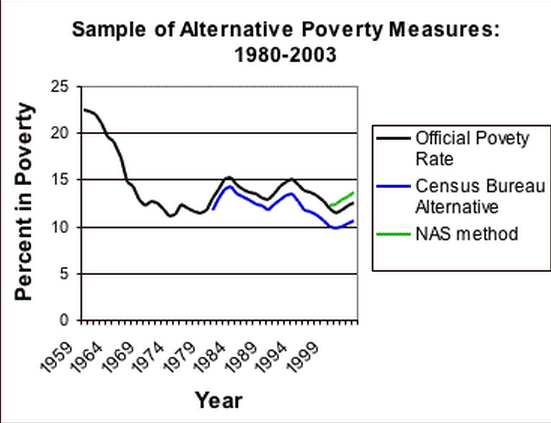

In the late 1950s, the poverty rate for all Americans was 22.4 percent, or 39.5 million individuals. These numbers declined steadily throughout the 1960s, reaching a low of 11.1 percent, or 22.9 million individuals, in 1973. Over the next decade, the poverty rate fluctuated between 11.1 and 12.6 percent, but it began to rise steadily again in 1980. By 1983, the number of poor individuals had risen to 35.3 million individuals, or 15.2 percent.

As you can see, the poverty rate declined sharply from 1959 to 1969, and then basically went sideways. Now of course if you include all sorts of benefit programs the numbers look better, and indeed I’ve done posts arguing that poverty on a consumption basis has fallen sharply in recent decades. But that’s when I’m responding to thoughtful inequality foes, not poverty wackos like Matt.

Matt wants you to believe that we don’t know what happened to poverty between the Warren Harding administration and what Paul Krugman considers the Golden Age of equality, the 1950s and 1960s, because we don’t know anything unless there is Official Government Data to back it up. I’m going to go out on a limb and claim that it is at least plausible to assume that poverty declined somewhat between 1922 and 1959. Indeed here again Matt misrepresents my argument. I never said we knew exactly what happened to poverty over the 45 years between 1922 and 1967, just that his arguments in favor of the War on Poverty made no sense unless we did know for a fact that it declined less during 1922-67 than during the 45 years after the War on Poverty began. And that seems exceedingly unlikely, give the data we do have, and what we all (should) know about what life was like in 1922.

The rest of his post is an exercise in changing the subject. He defines poverty as making less than 60% of median income. Then he argues there’s more poverty in countries with less redistribution. What a shock! So let’s see, if Cambodia does so much redistribution that the incentive to produce food falls to zero, and median per capita income falls to 25% above starvation level, then by definition Cambodia would have no poverty. After all, you would starve with only 60% of the median income, so the poor would not exist. Pol Pot produced one of the world’s most effective anti-poverty programs! According to Matt’s graph, the US has more poverty than Greece or Portugal (in 2005). If instead you look at actual living standards (square footage of living space for the poor, car ownership, home appliances, Medicaid, free public education, etc.), then the poor in the US don’t do so bad, even when compared to the richer European welfare states. But the poverty experts don’t want to eliminate poverty—what would they do then?

I’ll give Matt the last word:

Cleaving off some distribution and calling it “market” or “pre-tax” is just conceptually incoherent.

Couldn’t have said it better.