How many punches should Chuck Norris be allowed to throw?

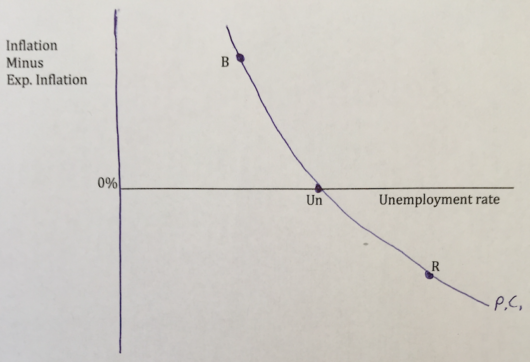

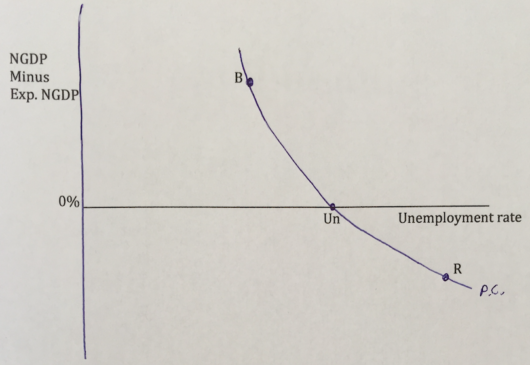

A number of market monetarist bloggers use the “Chuck Norris” metaphor for monetary policy credibility. The basic idea is that if the central bank credibly promises to do whatever it takes to hit its target, then NGDP growth expectations won’t fall very far, nominal interest rates will stay above zero, and the central bank won’t have to actually take many “concrete steppes” to hit its target. Exhibit A is the Reserve Bank of Australia, which never had to cut rates to zero or do QE during the global recession of 2008-09. And yet the Aussie outcome was better than in other advanced economies. The Chuck Norris metaphor refers to the fact that he can clear a room without throwing a punch, just due to his reputation.

Chuck Norris is a good metaphor, but (as far as I know) other bloggers have not fully fleshed out this line of reasoning. The focus has been on what central banks need to do, but perhaps the real focus should be on what governments need to authorize.

Consider two countries with central bank balance sheets equal to 5% of GDP, both on the eve of the Great Recession. In each case, the balance sheet balloons to 25% of GDP during the Great Recession. In which case is policy more expansionary?

Case A: The central bank is legally limited to a balance sheet of no more than 25% of GDP.

Case B: There is no legal limit on the central bank balance sheet.

In case B, the expansionary impact of the QE will probably be much greater than in case A. While the “concrete steppes” are identical, in case B there will probably be expectations of a more expansionary future policy than in case A. Nick Rowe often points out that the current concrete steps taken by central banks are far less important than changes in the future path of policy. That’s implicit in the Chuck Norris metaphor, and also an implication of state-of-the-art New Keynesian models developed by Michael Woodford and others.

At this point you might assume that the implication of my post is clear—don’t have legal limits on central bank balance sheets. But a decade of reading deep thinkers like Tyler Cowen and Robin Hanson (or petty much any of the George Mason bloggers) has convinced me that when it comes to human institutions, things are always more complicated than they seem, certainly more complicated than they seemed to me a decade ago. For instance, let’s add another case:

Case C: The central bank’s balance sheet is legally limited to 250% of GDP.

Now let’s think about Fed policy during the recovery from the Great Recession. We know that the Fed did three QE programs, and stopped when its balance sheet was just under 25% of GDP. We know that Bernanke cited vague “costs and risks” of doing even more QE. (Although we also now know from the FOMC transcripts that Bernanke himself was less concerned about these risks than other members of the committee.) And we know that some in Congress were complaining about all the money printing, and almost no one on Congress were complaining that they did not print enough money.

To summarize, while the Fed was in Case B, with no legal limit on their balance sheet, the institution behaved as if there was a sort of implicit limit, probably much lower than 250% of GDP. In that case, moving to case C might have actually been expansionary. The Fed would have thought, “Congress has our back, they authorize us to do truly massive QE if necessary to achieve our mandate.” Think of Russian highway speed limits changing from “no explicit limit but at the discretion of what the police officer views as unsafe” to “150 kilometers per hour”. Do speeds rise or fall?

In a perfect world, I’d want Congress to tell Chuck Norris that he’s authorized to throw as many punches as required to clear the room. Or perhaps to authorize a specific number that is clearly more than he would need (say 10,000 punches.) But I’m not sure about the idea of actually having Congress set a limit. If they had done so back in 2008, the limit on the central bank balance sheet would likely have been set too low.

Because Congress is so dysfunctional, and likely to remain so, one could argue that the Fed can pretty much do whatever they want. Who will stop them? The Fed is about 100 times more respected than Congress, and any Congressional attempt to control the Fed would almost certainly fail to get 51 votes in the Senate (which actually has a few grown-ups). There are plenty of pragmatic GOP senators (say among people like Lindsey, McCain, Flake, Collins, etc.), some of which would not support a right wing attempt to rein in the Fed. Heck I doubt even Trump would support it, as he knows he might need monetary stimulus if we again go into a recession. So perhaps the Fed could simply put on its Superman costume (sorry for mixing metaphors) and unilaterally announce that it views itself as being authorized to lower IOR to as much as negative 0.75%, and boost the balance sheet to as much as 250% of GDP, and then dare Congress to stop them.

That won’t happen (Larry Summers was not picked to be chair), but it’s the sort of issue we should be thinking about. Instead we think about question like “does QE work?” Which is such a dumb question it makes my hair hurt every time someone asks it.

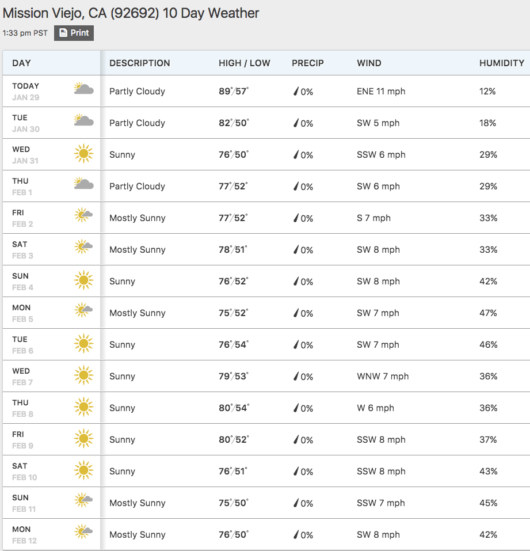

Update: People keep asking me how I enjoy California: