Tyler Cowen recently linked to a post by Gerard MacDonell on QE:

Last month’s Press Release from the FOMC announcing the first rate hike in a decade contained a seemingly-innocuous and yet telling discussion of the interaction between interest rate and balance sheet policy. It marked the end of false confidence in the efficacy of quantitative ease (QE), which can be traced to a technical error Ben Bernanke made while lecturing the Japanese on deflation in 1999.

The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases in the federal funds rate; the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run.

…The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction, and it anticipates doing so until normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way.

The passages above were not a major departure or surprise to the markets, but they confirm that the Fed leadership has now abandoned its original story about how QE affects the economy and has conceded that the tool is weak. If QE were strong, the balance sheet could not remain large even as the Fed promised to raise rates only gradually.

It has long been obvious that QE operated mainly through signaling and confidence channels, which wore off on their own without any adjustment in the size or composition of the Fed’s balance sheet. Accordingly, QE cannot be relied upon to provide much help in the next economic downturn, which means the Fed will have to tread carefully to avoid a return to the zero bound.

There’s a lot of confusion about QE, mostly because there’s a lot of confusion about virtually every aspect of monetary policy; including the most very basic aspects, such as what is it, and how we measure it.

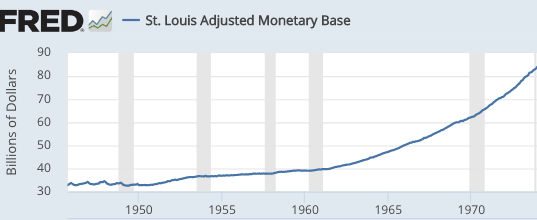

At one level QE is nothing new, it’s just changing the monetary base to impact the macroeconomy—what the Fed has been doing for many decades. With QE, the Fed also says that they are changing the base in order to affect interest rates on Treasury securities. But that’s also exactly what the Fed has been doing for many decades. And for many decades the impact of monetary shocks on long-term interest rates has been ambiguous. So that’s also nothing new.

And monetary policy has always been 1% about concrete actions and 99% about signaling. That’s also nothing new. So basically the argument that QE does not work is almost no different from the argument that monetary policy doesn’t work. But of course it is slightly different. QE is the term used for monetary policy that impacts the supply of base money at the zero bound. So it’s possible that this type of monetary policy is less effective, although the empirical evidence suggests that QE was effective in the US, and more recently in Japan. On the other hand future QE might not be effective, it entirely depends how it’s used. If monetary policy is 99% signaling, then the argument should not be about the 1% (QE) it should be about the 99% (signaling.) So the post by Gerard MacDonell isn’t so much right or wrong, as mostly beside the point.

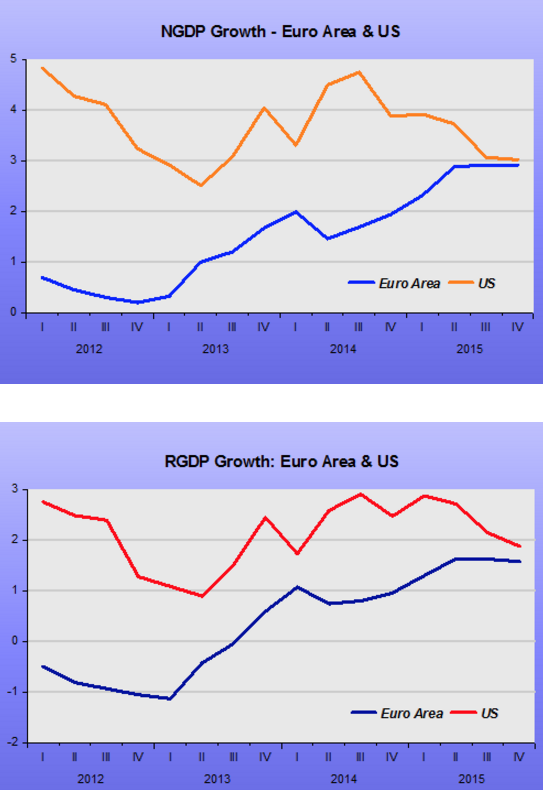

The success of future Fed policy will depend almost entirely on the signaling element. The Fed recently raised rates, which tells us that NGDP is about where they want it. And by backwards induction it seems like the Fed did not want rapid NGDP growth a few years ago, as if they had wanted it then they would not have raised interest rates this past December.

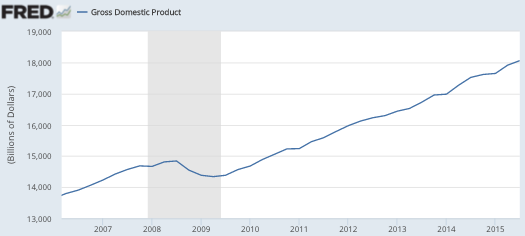

Here’s thought experiment that might help. Imagine a NGDP graph built on a large flat piece of plywood. Drive a stake into the point where NGDP was in mid-2009. Then drive another stake in where it was at the end of 2015. Connect the two pegs with a string and pull it tight, so that the string is taut. That’s the NGDP path that the Fed should have been favoring, if we assume that it was acting rationally. That is, it behaved over the past 6 years as if it wanted NGDP to growth at a roughly stable pace between the level of mid-2009 and late 2015. And guess what, that’s almost exactly how it did grow.

Now you might counter my claim by insisting, “Oh no, the Fed really hoped to get a much faster recovery, a much higher growth rate for NGDP.” Except there is just one problem with that alternative hypothesis—in that case it would not have been rational for them to raise rates in December. Because if the market knew (back in 2009) that the Fed would raise rates in December, then the intervening NGDP growth path would have been an equilibrium solution for the economy. (This is also approximately what New Keynesian theory says.)

Now for the curve ball. I think the person whining that the Fed actually preferred a faster recovery might be correct. Who’s to say? Maybe they were sincerely upset by the long drawn out period of high unemployment. Maybe they preferred faster NGDP growth. But even if all that were true, then everything I previously said would still be 100% correct. I said that if they were rational then their policy would have been consistent with the actual growth path, but I never said they were rational.

Perhaps they thought they could have their cake and eat it too—have a fast growth path then act very conservatively at precisely the moment they raised rates. Perhaps they never read Krugman’s 1998 paper. I can’t say. But if we assume the Fed was rational, then we have to also assume that QE “worked”. The Fed got exactly the recovery in NGDP that it was acting like it wanted.

When people debate whether QE “worked”, it’s not always clear what’s at stake. Obviously it worked in the sense of impacting market expectations; we know that from asset price responses to QE. But that doesn’t tell us much about the Fed’s (or BOJ’s) broader economic goals. I think it makes much more sense to focus on the Fed’s policy goals. What’s it actually trying to accomplish? Why doesn’t it tell us? What should it be trying to accomplish? Those are the issues that need to be debated, not whether QE “worked”.

PS. It’s equally beside the point to debate whether negative IOR “works”, or changes in reserve requirements “work”, or discount loans “work”. These are policy tools for achieving an objective, when the actual debate should be about the objectives.