The wrong lessons

The Economist has an article discussing how recent Japanese history provides some useful lessons for China. There are correct that Japan is a cautionary tale, but unfortunately they draw the wrong lessons:

And Mr Koo is himself keen to emphasize one “huge” difference between the two countries. When Japan was falling into a balance-sheet recession, nobody in the country had a name for the problem or an idea of how to fight it. Today, he says, many Chinese economists are studying his ideas.

His prescription is straightforward. If households and firms will not borrow and spend even at low interest rates, then the government will have to do so instead. Fiscal deficits must offset the financial surpluses of the private sector until their balance-sheets are fully repaired. If Xi Jinping, China’s ruler, gets the right advice, he can fix the problem in 20 minutes, Mr Koo has quipped.

Unfortunately, Chinese officials have so far been slow to react. The country’s budget deficit, broadly defined to include various kinds of local-government borrowing, has tightened this year, worsening the downturn. The central government has room to borrow more, but seems reluctant to do so, preferring to keep its powder dry. This is a mistake. If the government spends late, it will probably have to spend more. It is ironic that China risks slipping into a prolonged recession not because the private sector is intent on cleaning up its finances, but because the central government is unwilling to get its own balance-sheet dirty enough.

In other words, they are calling for China to make the same mistake the US has made in recent years, a reckless and irresponsible increase in fiscal deficits.

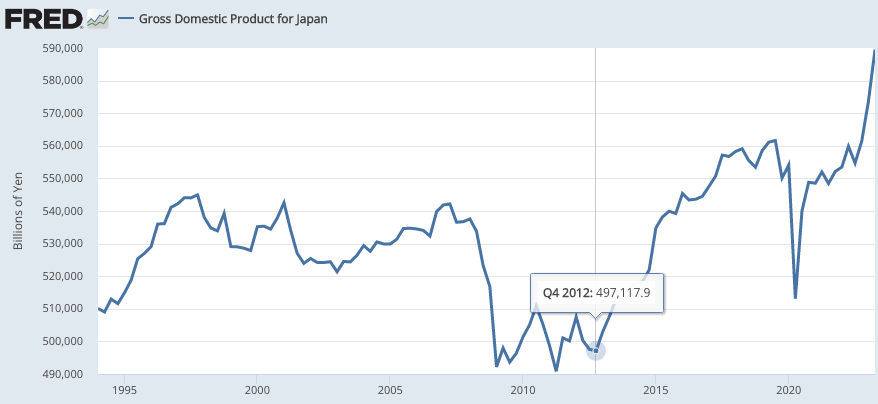

Japan ran huge budget deficits during the period from 1994 to 2012, partly under the influence of Western economists. The policy was a spectacular failure, with Japan seeing perhaps the weakest growth in aggregate demand ever seen over two decades, at least in a developed modern economy. By the end of 2012, Japan’s nominal GDP was actually lower than in early 1994:

When Prime Minister Abe took over at the beginning of 2013, he rejected this failed Keynesian advice, and switched to monetary stimulus. Over the following 21 11 years, Japan’s NGDP has risen by nearly 20%. Even that is too low—Abe should have switched to NGDP level targeting—but it’s a vast improvement over what came before. And fiscal policy actually became more contractionary, with several large increases in the national sales tax. Growth in the national debt slowed sharply.

Japan also has notable supply side problems. A country with such a high level of education and social cohesion should have a per capita GDP close to that of Germany or the Netherlands, not Spain or Italy. Thus monetary policy won’t solve all of Japan’s problems.

Similarly, China has some supply side problems, especially a high degree of investment in wasteful projects such as spectacular bridges in remote Guizhou province (which has 1/2 of the world’s tallest bridges). Those resources need to be redirected into more productive uses, such as high tech investments and consumption.

But if China does slip into a situation where there is a demand shortfall, the solution is not fiscal stimulus. Rather they need a “whatever it takes” approach to using monetary policy to sustain adequate growth in NGDP. Once the aggregate demand problem is fixed, it’s easier to address supply side issues.

PS. There is no such thing as balance-sheet recessions. Bad balance sheets are often the result of a bad monetary policy that sharply slows NGDP growth, leading to financial distress. When there are balance sheet problems, the natural interest rate often declines. If the central bank is targeting interest rates, this will cause an unintentional tightening of monetary policy. What looks like the cause of the recession (bad balance sheets) is more often the symptom. The underlying cause is bad monetary policy that leads to too little growth in NGDP.

Even when the balance sheet problems are unrelated to slowing NGDP growth (as is arguably the case in China), monetary policy still needs to adjust in order to prevent the decline in the natural interest rate from spilling over into a broader decline in aggregate demand.

PPS. In per capita terms, the post-2012 revival of NGDP growth was even more impressive.