Long and variable leads (a reply to Tony Yates)

Tony Yates expresses shock that someone calling himself a market monetarist could reject Milton Friedman’s famous “long and variable lags” claim about monetary policy.

I have great respect for Friedman, but when I did my research on monetary policy in the interwar years (which is the period where it is easiest to clearly identify monetary shocks) I wasn’t able to find significant lags. The monthly WPI and industrial production indices seemed to move almost immediately and sharply after monetary shocks. If NGDP data had been available, it would have also responded quickly.

Even worse, I found that Friedman and Schwartz had misidentified monetary shocks by focusing on the monetary aggregates, which often moved ahead of or behind the actual shock. Thus the devaluation that occurred in April 1933 led to expectations of future money growth, and these expectations led to an immediate surge in prices and output. That’s what led me to coin the “long and variable leads” phrase. I thought it would be obvious to people that I know that classical theories of causation don’t really allow for cause to follow effect. Rather that it is actually expectations of future money growth that caused the near term NGDP growth surge. I used a bit of poetic license to drive the point home.

Later I learned that Woodford and Eggertsson were doing similar research from a New Keynesian perspective. Here’s Yates:

Sumner cites Woodford and Krugman as commenting on the potency of expectations, and uses this in support of his thesis that changing expectations changing things refutes the long and variable lags thesis. But I am quite sure neither of them believe any such thing. Estimated versions of Woodford’s model (for example, the original Rotemberg-Woodford model) behave just like my account above. And Krugman is a firm believer in sticky prices, talking interchangeably between IS/LM and New Keynesian models. Which behave just as I’ve explained above.

The only model I know where monetary policy has its entire effect instantaneously is the flexible price rational expectations monetary model. And in this case there is no point in monetary stabilisation policy at all. Money has no short-run effects on output. Optimal policy in this model is to set rates at zero permanently, obeying the Friedman Rule. If there are real frictions in this model, like financial frictions, there will still be a role for fiscal stabilisation, however.

I’m sure these mix-ups would get ironed out if MaMos stopped blogging and chucking words about, and got down to building and simulating quantitative models. Talking of which….

Lots of problems here:

1. Obviously I’m a believer in sticky wage/price models, and hence do not believe that monetary policy has an instantaneous effect on all prices (although it does instantly impact the prices of commodities traded in auction-style markets.) So Yates has mischaracterized my views.

2. When Woodford’s coauthor Gauti Eggertsson tried to apply their approach to the Great Depression, he read a great deal of my empirical work, and seemed to like it. Eggertsson’s 2008 AER paper on monetary policy expectations in 1933 cites three of my empirical studies. That doesn’t mean he agrees with all my views, but he didn’t seem to find them ridiculous. And in 1993 I published a paper arguing that temporary currency injections would not be inflationary, 5 years before Krugman published “It’s Baaack . . .”

3. I can’t speak for all market monetarists, but I’m extremely skeptical of the VAR modeling approach discussed by Yates. The early attempts at VAR models produced a “price puzzle,” which meant that tight money seemed to “cause” higher inflation. I remember thinking “Yeah, what do you expect when you use interest rates as an indicator of the stance of monetary policy.” Yes, some of these problems have been “fixed”, but I’m not impressed by the fact that 99% of the economics profession seemed to think monetary policy was “easy” during 2008-09.

In my view economists should forget about “building and simulating quantitative models” of the macroeconomy, which are then used for policy determination. Instead we need to encourage the government to create and subsidize trading in NGDP futures markets (more precisely prediction markets) and then use 12-month forward NGDP futures prices as the indicator of the stance of policy, and even better the intermediate target of policy. It’s a scandal that these markets have not been created and subsidized, and it’s a scandal that the famous macroeconomists out there have not loudly insisted that it needs to be done.

If and when we get out of the Stone Age and have highly liquid NGDP and RGDP futures markets, then it would be much easier to explain my views on leads and lags. In that world a change in NGDP futures prices, not a change in the fed funds rate, represents a change in monetary policy. To be more specific:

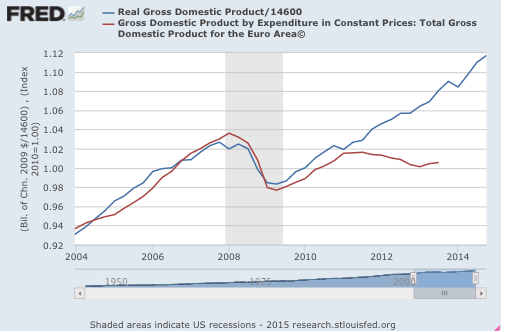

I predict that whenever the 12-month forward NGDP futures prices starts falling significantly, near term NGDP would fall at about the same time, or soon after. For instance, if we had had a NGDP futures market in 2008, then during the second half of the year you would have seen a sharp fall in 12 month forward NGDP futures. At roughly the same time or soon afterwards current NGDP would have been falling. In contrast, if the Fed had moved aggressively enough to prevent 12-month forward NGDP prices from falling, then near term NGDP in late 2008 would have been far more stable. I think that’s roughly consistent with Woodford’s view, although we may differ slightly on the lag between a change in 12-month forward NGDP expectations and a change in actual NGDP. (Nor would he necessarily accept my views on the potency of monetary policy in 2008.)

PS. The post also speculates on my views on fiscal policy. Just to be clear, I oppose attempts to force a balanced budget.

PPS. Yates’s blog is entitled “Longandvariable.” Not the specific post, the entire blog. He just needs to add “leads.”

PPPS. Yates refers to me as a “MaMoist.” I guess that’s better than being a Maoist, like that faction in the Greek party Syriza. You know, the party so many on the left now seem enamored with. The one that has a bunch of MPs that idolize history’s greatest mass murderer.

HT: Marcus Nunes