We need to unify monetary theory and monetary policy

Before today’s post, a few quick comments. I have a piece on Trump’s “deregulation” policies at MarketWatch. I have a Ted talk on public opinion at Econlog.

It’s clear to me that there is something seriously wrong with the field of monetary economics. The profession got 2008-09 almost entirely wrong. But it’s hard to pin down exactly where the problem lies. After all, there are increasingly sophisticated models being developed by economists who are much smarter than me. These models feature rational expectations, and all the other bells and whistles you might want. I regret their focus on interest rates and inflation, but that doesn’t fully explain the problem. While I prefer to talk about money and NGDP, anything that I believe can be translated into New Keynesianism by referring to the gap between the natural rate of interest and the market rate. So where’s the problem?

In my view, the problem lies in the interface between sophisticated theoretical models and a very crude discourse on monetary policy. This monetary policy discourse is little changed from 90 years ago, and not at all informed by recent developments in theory.

John Hall directed me to a James Hamilton post that included this remark:

Zhang’s suggested solution begins with the observation by Gurkaynak, Sack and Swanson (2005) that the news revealed by a typical FOMC announcement is multidimensional. The Fed is typically both changing the current interest rate and signaling the changes that are in store for the future.

Here’s my hypothesis. Monetary models suggest that monetary policy actions are multidimensional, while most of the discourse on real world monetary policy treats policy as one dimensional—easier or tighter money, lying along a single line. This has led to the confusing debate between Keynesians and NeoFisherians, which I’ll return to later.

Once monetary theorists understood that monetary policy actions affected the entire future path of policy, the modeling problem became more difficult. At this point they should have stopped basing their models on interest rates, as this variable creates all sorts of indeterminacy issues, or perhaps I should say makes these issues even harder to grapple with—they can also occur when using money itself.

To make things simpler, I’m going to boil the multidimensional theoretical models down to two dimensions—levels and growth rates. Obviously things are more complicated than that, but it’s enough to make my point about the disconnect between monetary theory and the modern discourse on monetary policy. I’m also going to work with some alternative monetary instruments, that is, alternatives to interest rates.

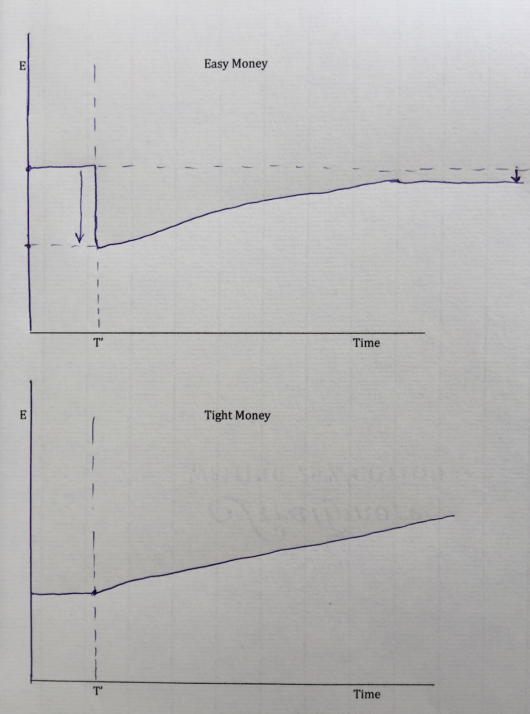

Let’s start with the monetary base. Any change in monetary policy has two dimensions, a level shift and a growth rate shift. Thus the Fed might immediately increase the base by 3%, but not change its expected growth path going forward, or they might keep the level of the base as is, but announce a faster growth path for the base. In practice, most monetary policy shocks probably involve a bit of each. You could plot them using a graph with the X axis being the immediate change in the level of the base, and the Y axis being the change in the expected growth rate of the base.

Elsewhere I’ve argued that Keynesian economics is basically about level shifts, and monetarism is basically about growth rate shifts. But old monetarism is mostly gone, so I’ll instead describe these two dimensions of monetary policy as “Keynesian” and “Fisherian”. No “neo” is necessary in front of Fisherian, for reasons that will later become clear.

Thus if the Fed suddenly announces a 3% rise in the base, and also announces that henceforth the growth rate of the base will be reduced by 1.8%/year, then the policy would be described as “Keynesian monetary stimulus and Fisherian monetary contraction.” Terms like “easy money” and “tight money” are no longer sufficient in this multidimensional world. And keep in mind that this multidimensional approach comes right out of modern monetary theory. (Not “MMT”, I mean actual cutting edge monetary theory.)

Unfortunately, money demand shocks leave money as an unsuitable instrument for policy analysis.

I eventually plan to link this up to the Keynesian/NeoFisherian debate. To do so, we’ll run through the exact same exercise, but this time using the exchange rate as the policy instrument. (As is the case in Singapore, for instance.) A Keynesian policy change is a one time adjustment in the exchange rate. A Fisherian policy change is a change in the expected growth rate of the exchange rate. In the Dornbusch overshooting model, an increase in the money supply causes a fall in interest rates (to levels below the alternative currency.) This leads to a one-time depreciation in the exchange rate. But the interest parity condition implies that (with lower interest rates) the exchange rate is expected to appreciate relative to the alternative currency. With Dornbusch overshooting the currency still depreciates in the long run; the Keynesian effect outweighs the Fisherian effect. But that need not be true in all cases.

In January 2015, Switzerland simultaneously appreciated its currency sharply, and dramatically cut interest rates. The effect was a policy that was contractionary in both the Keynesian and Fisherian sense. The Swiss franc immediately appreciated sharply, and was expected to continue appreciating over time (due to the low rates). In a few cases, exactly the opposite occurs, usually in developing countries experiencing a crisis. Thus places like Argentina or Indonesia might see their currency sharply depreciate in a crisis, and also see a huge rise in interest rates—which is a forecast of further depreciation (according to the interest parity condition.) BTW, the interest parity condition does not hold perfectly true in the real world, but that’s not important for the points I’m making. No macro model holds perfectly true—it’s a model, a stylized picture of reality.

When the US announced the QE of March 2009, the dollar plunged sharply and interest rates fell. That was an example of Dornbusch overshooting, Keynesian monetary stimulus dominating Fisherian monetary contraction. By “dominating”, I mean that in the long run the exchange rate ends up lower than before the shock, despite appreciating after the original overshoot lower. It was easier money, in net terms.

Now let’s imagine the X/Y policy graph I described as a vast plain, with economists living on that featureless surface. Some economists are only able to see things along the X-axis direction. We’ll call these economists “Keynesians”. They think lower interest rates represent easier money. Others only see things along the Y-axis. We’ll call these economists “NeoFisherians.” They believe lower interest rates represent tighter money. Others can see in two dimensions, we’ll call them “monetarists”. They do not believe that interest rates tell us anything useful about the stance of monetary policy.

Comments and suggestions are welcomed.

PS. I’d rather not use money or exchange rates as a monetary indicator, rather I’d prefer to rely on NGDP futures prices. The level/growth rate distinction also applies there, but is complicated by the fact that NGDP responds slowly to shocks. Thus unlike with exchange rates, “level shifts” actually take a bit of time. Recall mid-2008 to mid-2009, which was a sort of level shift down in NGDP, of roughly 8% below trend. Then the growth rate going forward also fell by about 1%, from 5% to 4%.