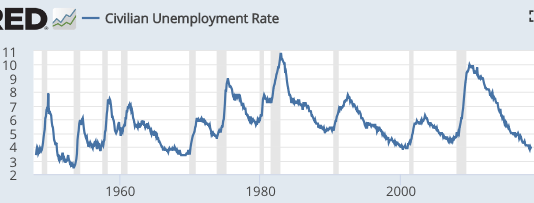

Economic indicators and the risk of “lowflation”

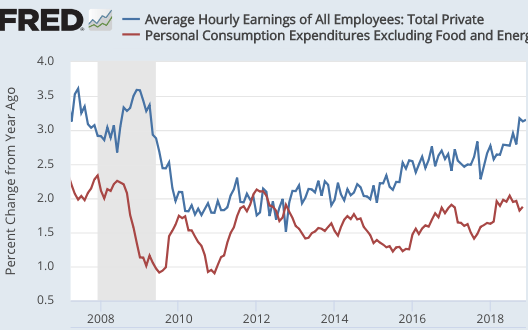

As we enter 2019, there are some economic indicators worth thinking about. Some are obvious, like the strong jobs growth (stronger than I expected.) Some are more subtle. Here are wage inflation (blue) and core PCE inflation (red):

In my view, wage inflation is far more meaningful. But PCE inflation is what the Fed is targeting, so we also need to pay attention to that variable. I’d expect it to follow wage inflation, but the relationship is weak.

In my view, wage inflation is far more meaningful. But PCE inflation is what the Fed is targeting, so we also need to pay attention to that variable. I’d expect it to follow wage inflation, but the relationship is weak.

BTW, I noticed a problem with the way they calculate core inflation, at least for the CPI. It does not include food consumed away from home. In my view, restaurant meals are one of the most “core” of all core inflation components, or should be. The whole point of core inflation is to include stuff closely related to wage inflation, which is very inertial. And yet food away from home (6% of the CPI) is considered part of “food and energy”, and excluded from core. In contrast, I’m not sure shelter should be included in core inflation, as real estate price measures are not reliable. But this component (1/3 of the CPI) is a part of core inflation. This link gives the weights of the CPI basket. The CPI is just a mishmash of unrelated and hard to measure stuff.

This is one reason why I’m less concerned with “lowflation” than many other people. Wage inflation is steadily rising, and is approaching pre-recession rates. We seem headed in the right direction. NGDP growth has also been strong.

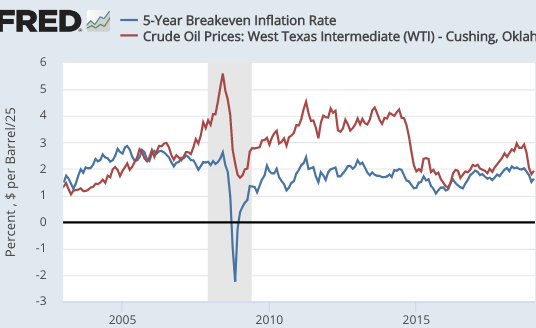

Private forecasters predict roughly 2% inflation going forward, while the financial markets seem to predict less than 2%. How much less? That’s hard to say.

The 5-year TIPS spread is about 1.65%. But CPI inflation has exceeded PCE inflation by 0.25% over the past decade, so in fact the true TIPS spread (for PCE) is around 1.4%, well below the Fed target. That may be partly due to two factors. One is the recent fall in oil prices. For various reasons including lags in adjustment, TIPS spreads tend to follow oil prices (the graph divides oil prices by 25, to make comparisons easier to see):

The the sharp fall in oil prices in 2015 pushed the TIPS spread down from 2% to 1.3%. Or at least it seemed to. I have trouble understanding how the effect could be that large. The recent drop should not have reduced 5-year TIPS spreads more than about 0.2%. So that leaves perhaps a 1.6% market PCE inflation forecast over 5 years—still lower than target.

The the sharp fall in oil prices in 2015 pushed the TIPS spread down from 2% to 1.3%. Or at least it seemed to. I have trouble understanding how the effect could be that large. The recent drop should not have reduced 5-year TIPS spreads more than about 0.2%. So that leaves perhaps a 1.6% market PCE inflation forecast over 5 years—still lower than target.

Can a liquidity premium for T-bonds explain this gap (as in late 2008)? Maybe, but I lean toward the view that the market really does forecast slightly below 2% inflation, say 1.7% or 1.8%. This might reflect a 50% chance of continued boom and 2% inflation, and a 50% chance of recession and only 1.5% inflation, for instance.

Another variable of interest is fed funds futures. They normally show a rising trend over time. Right now the current fed funds rate is around 2.4%, expected to fall to 2.3% in July 2020. So that tells me that the market expects a bit of “lowflation” in 2019, which might eventually lead to a rate cut. But no recession. Of course the market is presumably pricing in a certain probability of continued boom and higher rates, and a slightly higher probability of a sizable rate cut if there is lowflation and/or recession.

In my view, 2019 will tell us a great deal about whether we have moved to a higher trend rate of growth, and/or whether policy is still too tight to hit the Fed’s 2% PCE inflation target. It’s not impossible that both might occur—sub-2% core PCE inflation and RGDP growth above the Fed’s forecast. This would actually be good news in a way, as the “lowflation” would mean the Fed would not have to act to slow the recovery, which then might extend for many more years. I don’t predict stocks, but the goldilocks outcome might be good for equities.

PS. I’m reluctant to mention stocks as an forecasting tool, because they are so noisy. They are affected by NGDP growth, but also by trade wars, foreign growth, and other factors. The partial recovery from late last year makes a recession slightly less likely, although I never thought the risk had reached a 50% probability. The fairly flat yield spread points to slower growth but no recession—similar to fed funds futures.

PPS. I’m tempted to call a Chinese recession. If I were right it would look very good, given how I pooh-poohed all the other pundits who wrongly predicted a Chinese recession in previous years. But I won’t. No guts, no glory. And I have no guts. I predict they’ll muddle through.