Francis Coppola on negative interest rates

Tyler Cowen linked to a post by Frances Coppola:

But one thing seems clear. How negative rates would work in practice is no clearer than how QE works in practice. They are experimental, and their effects are complex. Hydraulic monetarist arguments (“if you can get rates low enough the economy will rebound”) are simplistic.

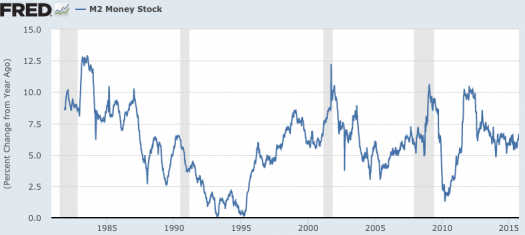

Monetarist? Don’t they focus on the money supply and/or NGDP expectations? Most people would consider Milton Friedman a monetarist, and here’s what he had to say about low rates:

Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy. . . .

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.

In a monetarist model, lower market interest rates are contractionary for any given monetary base, because they reduce velocity. It’s the Keynesians who are likely to claim that lower rates are expansionary. Now of course Friedman was talking about market interest rates, not IOR. Lower IOR is theoretically expansionary, and so far markets have reacted to negative IOR announcements as if they are expansionary.

Will that be true in the future? Nothing is certain, as monetary policy is very complex, and concrete action A can always be interpreted as a signal of future concrete action B. Anything is possible. A $1 billion increase in the base can have a contractionary impact if a $2 billion increase was expected. But any monetary analysis should start from the presumption that reducing the demand for an asset will reduce its value. A reduction in the value of base money is expansionary. That means lower IOR has a direct expansionary impact on NGDP. (Secondary effects are complex, as Coppola suggests.)

Indeed, individual banks can avoid paying negative rates on excess reserves. They can discourage customers from making deposits; they can choose to hold reserves in the form of physical cash; or they can increase new lending (not refinancing), since the balance sheet result of new lending is replacement of reserves with loan assets.*

But of course the reserves do not disappear from the system. They simply move to another bank, which then incurs the tax. The banking system AS A WHOLE cannot avoid negative rates on reserves. The reserves are in the system, so someone has to pay the negative rate. If banks increase lending to avoid the negative rate, the velocity of reserves increases. It’s rather like a game of pass-the-parcel.

This is a common misconception, which I see all the time. If individual banks don’t want to hold a lot of excess reserves, they can simply buy other assets with them. If the banking system as a whole wants to reduce its holding of excess reserves, it can reduce the attractiveness of deposits until the excess reserves flow out into currency held by the public. The central bank controls the monetary base, not bank reserves. The composition of the base is determined by banks and the public.

It seems reasonable to suppose that negative interest rates might increase loan demand. Negative interest rates on reserves put downwards pressure on benchmark rates and thus on bank lending rates, attracting those who would otherwise be priced out of borrowing. But typically those are riskier borrowers. We have just spent eight years forcing banks to reduce their balance sheet risk. Do we really want to force banks to lend to riskier borrowers? Of course, tight underwriting standards could be used to deny those people or businesses loans: but doesn’t that rather defeat the purpose of negative rates? It’s something of a double bind.

We need an easier money policy and, if banks are taking excessive risks, a tighter credit policy. It’s best not to mix up monetary and credit issues. Negative IOR is about reducing the demand for base money, which is inflationary; it’s not about increasing bank loans. Central banks should not be trying to encourage more debt creation—unless you want to end up like China (where the policies are unfortunately linked together.)

In the end I agree with those who are skeptical of negative interest rates. These ultra-low interest rates are a sign that monetary policy is too contractionary. The developed world needs much higher interest rates, but only if we get there with an expansionary monetary policy. In December the Fed tried a short cut, raising rates without boosting NGDP growth. This is putting the cart before the horse. You need to generate higher NGDP growth expectations first, and then you can achieve a permanently higher level of interest rates.