I’m still seeing overwhelming confusion in the media about the definition of a recession, and more importantly, what a recession actually is. Here’s the BEA, which computes GDP:

Recession: how is that defined?

In general usage, the word recession connotes a marked slippage in economic activity. While gross domestic product (GDP) is the broadest measure of economic activity, the often-cited identification of a recession with two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth is not an official designation. The designation of a recession is the province of a committee of experts at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a private non-profit research organization that focuses on understanding the U.S. economy. The NBER recession is a monthly concept that takes account of a number of monthly indicators””such as employment, personal income, and industrial production””as well as quarterly GDP growth. Therefore, while negative GDP growth and recessions closely track each other, the consideration by the NBER of the monthly indicators, especially employment, means that the identification of a recession with two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth does not always hold.

And here is the NBER, the group that economists consider authoritative on all questions about definitions of recessions:

Q: The financial press often states the definition of a recession as two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. How does that relate to the NBER’s recession dating procedure?

A: Most of the recessions identified by our procedures do consist of two or more quarters of declining real GDP, but not all of them. In 2001, for example, the recession did not include two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. In the recession beginning in December 2007 and ending in June 2009, real GDP declined in the first, third, and fourth quarters of 2008 and in the first quarter of 2009. The committee places real Gross Domestic Income on an equal footing with real GDP; real GDI declined for six consecutive quarters in the recent recession.

Q: Why doesn’t the committee accept the two-quarter definition?

A: The committee’s procedure for identifying turning points differs from the two-quarter rule in a number of ways. First, we do not identify economic activity solely with real GDP and real GDI, but use a range of other indicators as well. Second, we place considerable emphasis on monthly indicators in arriving at a monthly chronology. Third, we consider the depth of the decline in economic activity. Recall that our definition includes the phrase, “a significant decline in activity.” Fourth, in examining the behavior of domestic production, we consider not only the conventional product-side GDP estimates, but also the conceptually equivalent income-side GDI estimates. The differences between these two sets of estimates were particularly evident in the recessions of 2001 and 2007-2009.

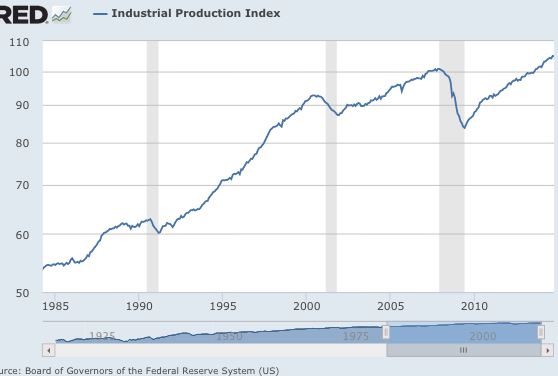

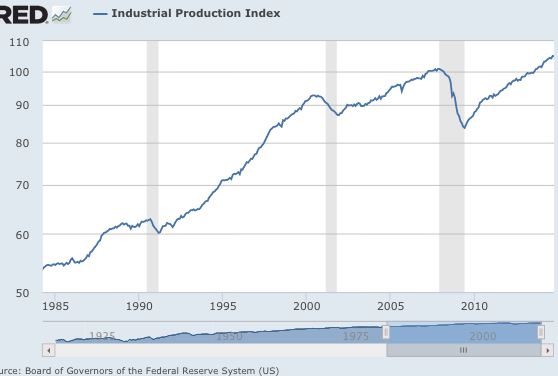

Fortunately, when you look at various monthly indicators, it is usually incredibly easy to date recessions—they look really, really different. Here’s industrial production over the past 30 years, how many recessions can you spot?

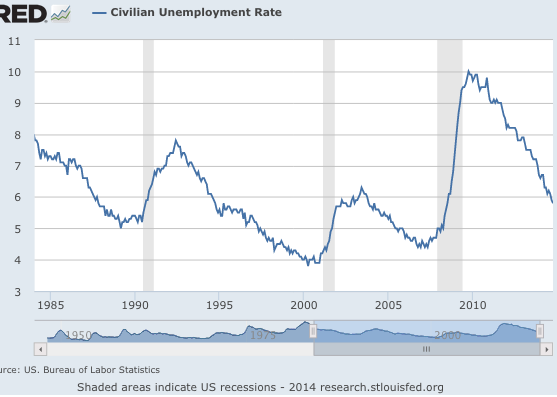

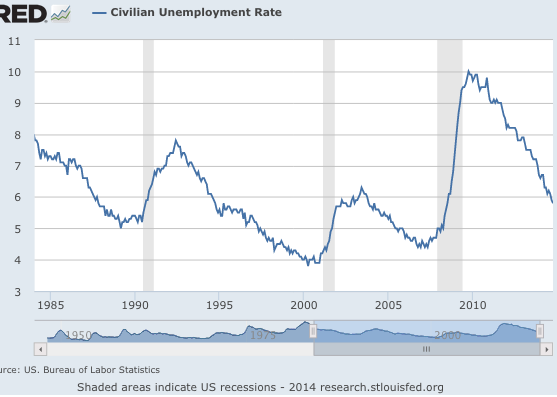

For those readers still struggling with the question, let’s try the unemployment rate:

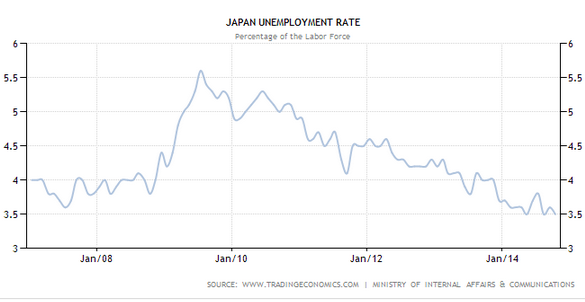

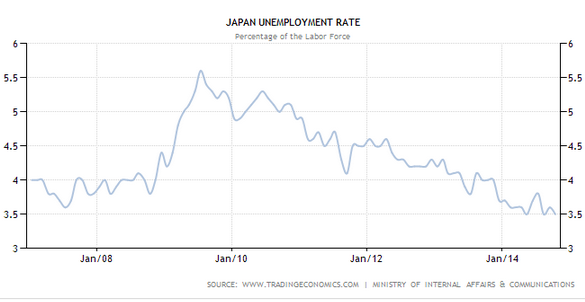

Interesting how the answer “3” keeps popping up. But the “2 quarters of falling GDP” proponents insist that 2001 was not a recession (even though economists almost universally agree it was), and that Japan has recently experienced a recession, despite a falling unemployment rate.

Recessions really are distinct events. Why does this matter? Isn’t it just a question of semantics? By now it should be obvious that words matter. Many economists think in terms of words, not reality. The map, not the territory. Distinguished economists tell me to stop harping on the definition of “tight money.” But it’s precisely because most economists thought money was easy in 2008 that they don’t believe the recession was caused by a tight money policy of the Fed. If the Fed had suddenly raised the fed funds target to 8% in early 2008, they would have blamed the recession on the Fed. They wrongly exonerated monetary policy becasue they don’t understand the meaning of the term ‘tight money.’ In the same way, pundits who wrong believe Japan entered a recession this year are more likely to believe that monetary stimulus in Japan has not boosted AD, whereas it clearly has.

PS. One LA Times story claimed that Japan has had 4 recessions since 2008! And no, I’m not joking. When looking at the following graph keep in mind that sampling errors explain movements of a few tenths of percent. How many recessions can you spot?

PS. I have a new post on oil prices at Econlog.