About that “malinvestment”

When I first started blogging, a number of Austrian commenters told me the real problem was not tight money. Rather there had been “malinvestment” in housing, especially in the “sand states”. The recession was the price we had to pay for all of this poorly thought out investment.

That theory never even made sense in 2009. If the problem was malinvestment in housing, then resources would have shifted to the other 95% of the economy. Instead, output fell in almost all sectors. (I’m referring to 2008-09; resources did shift to other sectors during the 2006-07 construction slump.)

Today it makes even less sense. The NYT has an article on the housing market in North Las Vegas, which was the epicenter of the bust. It’s now booming:

Amazon has opened two huge centers in North Las Vegas for distributing goods and handling returns, bringing thousands of jobs. A third facility is on the way. Sephora, the cosmetics company, recently broke ground here for a giant warehouse.

With nearly a quarter-million people, North Las Vegas is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country. It’s also young — the average resident is just 33 years old.

The Times reports that prices are soaring and homes typically sell in three days.

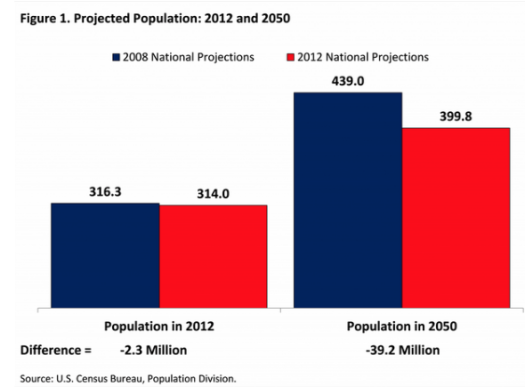

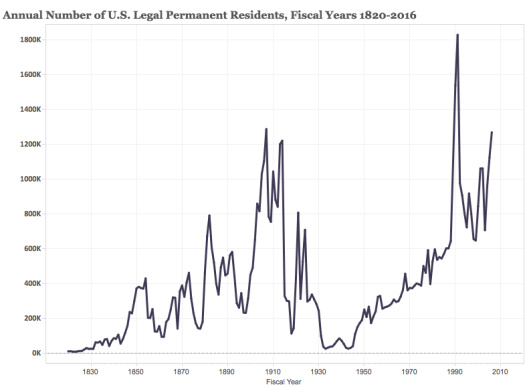

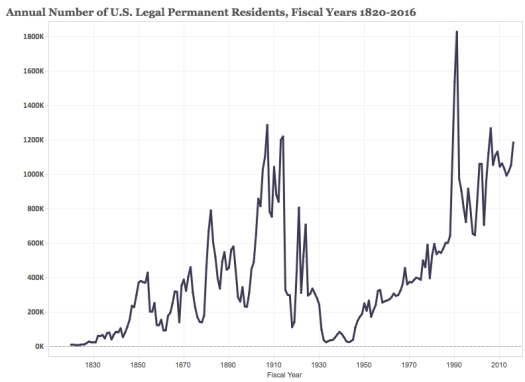

I agreed that there had been some excessive housing construction in the inland portion of the sand states, perhaps because builders expected the US population in 2050 to be 50 million higher than is now predicted. (Recall that 2006 was the year of the immigration crackdown.) But I argued that these cities were fast growing, and this problem was relatively mild. In my view the malinvestment is better termed “too early investment”—some houses were built a few years before they were needed. The Austrian counterargument was that these houses would remain empty for decades, and eventually depreciate sharply (in a physical sense.) It looks like I was closer to the truth.

I would add that Kevin Erdmann’s take on the crisis is being increasingly confirmed by events:

Jazzmine Guiberteaux moved here a few years ago from Oakland, Calif. — one of many California real estate refugees who headed to Nevada in search of more space and cheaper housing. But she is increasingly being priced out.

A 35-year-old mother of two, with another child on the way, she works in a clothing shop and drives for Uber to earn extra cash. She has had to move three times in five years.

Ms. Guiberteaux’s previous landlord terminated her month-to-month lease on Mother’s Day. It took her 10 days to get a new place. “The rent is higher,” she said. “But it’s in a better neighborhood.”

When Kevin’s book comes out in a few months, it may end up being the most important housing book of the decade.

BTW, the NYT has this picture of a downtrodden resident, who is forced to rent rather than own:

You can see the picture more clearly in the NYT article. I couldn’t help but notice the Pottery Barn look. The downtrodden have certainly come a long way from the 1960s, when the NYT carried pictures of shacks in Appalachia and slums in the Bronx.

I know, I’m a heartless out of touch elitist who doesn’t understand how much people are suffering.

PS. Ten years after Lehman, market monetarists should feel really good about how things are playing out. Not only is the boom in the housing market tending to confirm the MM/Erdmann view of the world, but more and more policymakers are talking in terms that sound suspiciously market monetarist. Clare Zempel directed me to an article discussing Janet Yellen’s take on what we should do next time:

Elaborating on how the central bank should think about what to do if rates have to be cut to zero again in the future and can’t go any lower, she said the Fed should promise now that it will keep rates low enough to let a hot economy make up for lost time.