Dr. Copper and Mr. Gold: A conversation

Dr. Copper: We need the Fed to aggressively ease monetary policy.

Mr. Gold: I don’t know what you are talking about, they should raise rates now.

Dr. Copper: But NGDP has only increased 4% in three years; normally it would rise at least 15% over that time span.

Mr. Gold: But the Fed’s mandate isn’t NGDP, it’s an inflation targeter.

Dr. Copper: Actually, its mandate is stable prices and high employment. Unemployment is 9.1%.

Mr. Gold. But we all know the Fed can’t target employment in the long run, better to focus on 2% inflation.

Dr. Copper: But core inflation has been below 2% in recent years.

Mr. Gold: People can’t live without food and oil, who cares about core inflation?

Dr. Copper: But even headline inflation has averaged only about 1% in the past three years.

Mr. Gold: It’s not the past that’s important, it’s the future, and inflation is rising sharply.

Dr. Copper: But the TIPS markets say even headline inflation will be under 1.5% over the next five years.

Mr. Gold: Don’t you understand; these low interest rates will create another asset price bubble, just like in 2003-06.

Dr. Copper. Oh, so you do favor looking at asset prices. I thought you wanted a single mandate; headline inflation.

Mr. Gold: Well . . . consumer inflation is important, but asset prices should be part of the index.

Dr. Copper: But housing prices are down 32%, and still falling. So if we added assets to the CPI wouldn’t it show deflation? Or do you just favor paying attention to asset prices when they are high?

Mr. Gold: Face it; you are just trying to bail out irresponsible borrowers.

Dr. Copper: That’s not true, but would it be so bad if the debt crisis was lessened as a side effect of monetary stimulus?

Mr. Gold: The Fed should not be adding to moral hazard, they need to focus like a laser on price stability.

Dr. Copper: But didn’t they bail out the big banks in 2008? Why not a little help for middle class homeowners?

Mr. Gold: Because they aren’t too big to fail.

Dr. Copper: But isn’t there evidence the entire world economy is headed for a slump? Michael Darda predicts Europe’s NGDP will decline in 2012. China is slowing rapidly. US personal income growth has now turned negative. Japan is still in deflation. Aren’t you worried?

Mr. Gold: Yes, but countries like Australia are still doing quite well.

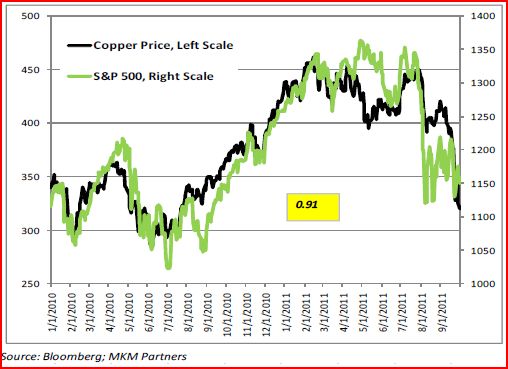

Dr. Copper. OK, now for my ace in the hole. The price of copper is widely known as the gold st . . . er, the copper standard of all forecasters. It has an amazing record of accuracy in predicting the world economy, and look at where it’s headed:

Mr. Gold: Pffft. Copper is what pennies and farthings are made out of; gold is the metal of crowns and guineas.

Dr. Copper: But even gold prices have plunged nearly $300 dollars in recent weeks!!

Mr. Gold: Well why didn’t you say so; fire up the helicopters.

Update: Johnleemk created this animated version of the conversation.