Christian List directed me to some studies of the costs of IP theft. The first link was to an AEI report on the subject, which criticized the US definition of IP theft:

The leaders of the IP commission, Admiral Dennis Blair and General Keith Alexander, penned an opinion piece last year that not only points the finger directly at China but also illustrates confusion as to just what the US should target. They stated: “Chinese companies, with the encouragement of official Chinese policy . . . have been pillaging the intellectual property of American companies.” They listed a large array of US economic sectors as examples, including automobiles, chemicals, aviation, pharmaceuticals, consumer electronics, and software, among others.

But even these two highly knowledgeable leaders then went on to confuse the US case against Beijing’s “pillaging” by adding a list of military IP thefts, including plans and designs related to the F35 fighter, the Patriot missile system, the Aegis Combat System, thermal imaging cameras, and unmanned underwater vehicles, among others, as examples of Chinese spying operations. The problem and confusion to the reader here is that such military espionage is considered fair game by all nations, including the US. And one hopes that US intelligence agencies have been equally diligent in ferreting out Chinese (and other nations’) advanced military designs and equipment.

Chinese theft of US military secrets is certainly something that the US should be concerned about, and try to prevent. But perhaps the moralistic tone one sees is a bit inappropriate, given that the US government does the same thing. I’m all for trying to prevent this sort of espionage, but here I’ll focus on commercial theft, which seems to be the bigger issue. The AEI piece linked to a 2017 US government report on IP theft. Indeed the term ‘theft’ is used right in the subtitle of the report:

THE THEFT OF AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: REASSESSMENTS OF THE CHALLENGE AND UNITED STATES POLICY

I was thus surprised to see the report discuss activities that cannot possibly be regarded as “theft”:

China continues to obtain American IP from U.S. companies operating inside China, from entities elsewhere in the world, and of course from the United States directly through conventional as well as cyber means. These include coercive activities by the state designed to force outright IP transfer or give Chinese entities a better position from which to acquire or steal American IP.

I.e., we’ll let you invest in China if you share technology. In fairness, most of the report does focus on three types of outright IP theft:

We estimate that the annual cost to the U.S. economy continues to exceed $225 billion in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets and could be as high as $600 billion.

Wait until you see where they got these numbers:

Counterfeit and pirated tangible goods.

In 2016, the OECD and EUIPO used worldwide seizure statistics from 2013 to calculate that up to 2.5%, or $461 billion, of world trade was in counterfeit or pirated products.23 By applying this percentage to U.S. trade, we estimate that in 2015 the value of these goods entering the U.S. market was at least $58 billion.

The United States, however, is a much larger market for imports than the average market. It is nearly equivalent in size to the European Union, where the OECD/EUIPO study determined that approximately 5% of imports are counterfeit or pirated tangible goods. By using 5% as a proxy for the proportion of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods in U.S. imports ($2.273 trillion),25 we estimate that the United States may have imported up to $118 billion of these goods in 2015. Thus, anywhere from $58 billion to $118 billion of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods may have entered the United States in 2015. This represents the approximate value of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods (not services) entering the country.

With respect to counterfeit and pirated tangible U.S. goods sold in foreign markets, the OECD/EUIPO study found that they accounted for nearly 20% of the value of reported worldwide seizures. In 2015, estimated worldwide seizures of counterfeit goods totaled $425 billion, meaning that as much as $85 billion of counterfeit U.S. goods (20% of worldwide seizures) entered the world market (including the U.S. market).

Certainly, in the absence of counterfeit goods some sales would never take place, and thus the value of illegal sales is not the same as the sales lost to U.S. firms. The true cost to law-abiding U.S. firms in sales displaced due to counterfeiting and pirating of tangible goods is unknowable, but it is almost certain to be a significant proportion of total counterfeit sales. For purposes of aggregating the total cost to the U.S. economy of IP theft, we have estimated that 20% of counterfeits might have displaced actual sales of goods. When applied to the low-end estimate ($143 billion) of the total value of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported into the United States and counterfeit and pirated tangible U.S. goods sold abroad, the conservative estimate of the cost to the U.S. economy is $29 billion. When applied to the high-end estimate ($203 billion), the cost to the U.S. economy is estimated at $41 billion.

“Displaced”? So let me get this right. If my wife buys a Coach handbag for $100, and it’s a counterfeit from China, and she enjoys the handbag, then the “cost” to America is $100? I’m guessing that no actual economists participated in the writing of this government report.

Update: Bob Murphy pointed out that my wording was wrong. I should have said; “So let me get this right. If my wife buys a Coach handbag for $100, and it’s a counterfeit from China that displaces the sale of an American handbag, and she enjoys the handbag, then the “cost” to America is $100?”

Otherwise, my point is the same.

You might argue that my handbag example trivializes the problem, and that the real problem is patent infringement, which slows innovation. I agree. But how big a problem is patent infringement? And how to patent an idea with InventHelp successfully? Again, the US government:

The same OECD/EUIPO study found that while 95% of counterfeit goods seized by customs officials were protected by trademarks, only 2% were counterfeits of patent-protected goods.

Here is the summary data for all three types of IP theft:

Totaling It All Up

In summary, we estimate that the total low-end value of the annual cost of IP theft in three major categories exceeds $225 billion, or 1.25% of the U.S. economy, and may be as high as $600 billion, based on the following components:

• The estimated low-end value of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported and exported, based on a conservative estimate that 20% of the cost of these goods detracts from legitimate sales, is $29 billion. The high-end estimate for counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported and exported is $41 billion.

• The estimated value of pirated U.S. software is $18 billion.

• The estimated low-end cost of trade secret theft to U.S. firms is $180 billion, or 1% of U.S. GDP. The high-end estimate is $540 billion, amounting to 3% of GDP.

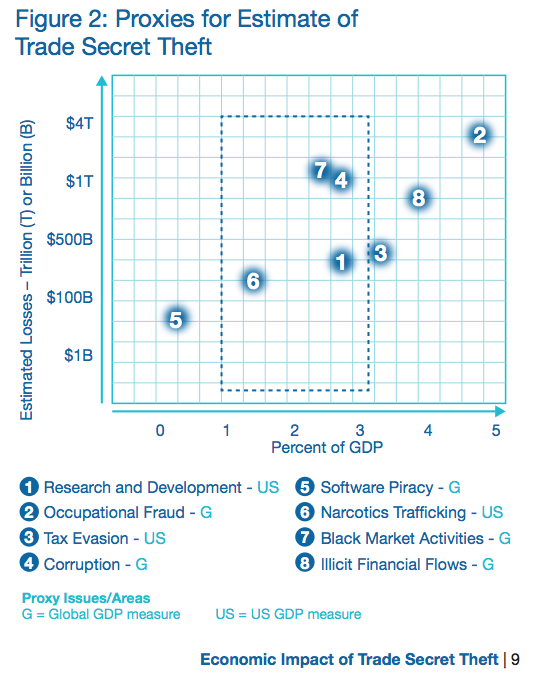

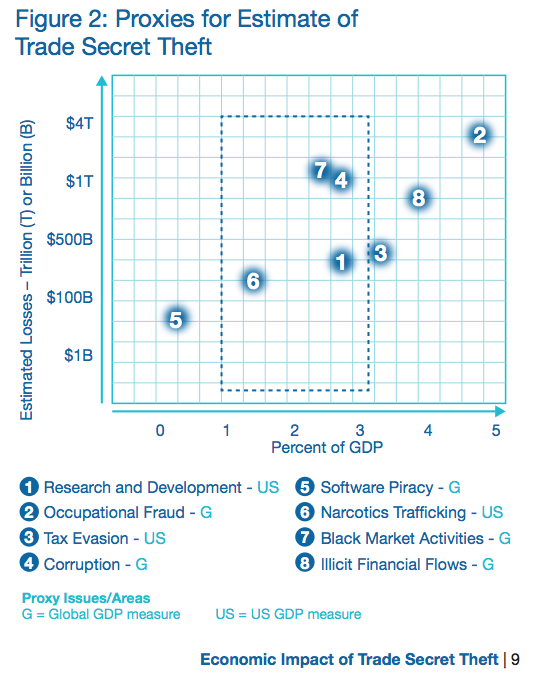

The software estimates are flawed in much the same way as the pirated goods estimates. But it really doesn’t matter, because the total estimated cost of IP theft is almost entirely driven by the third category (trade secret theft), especially when you consider that the first two categories use methods that exaggerate the costs by at least an order of magnitude—indeed it’s not obvious that there are any net costs at all. So where does the trade secret data come from? The report doesn’t provide any methodology, merely citing a PriceWaterhouseCoopers study. The following graph summarizes the methods employed by PWC:

PWC have done the following. They start with the admission that they have no idea how to directly estimate the losses from trade secret theft. Instead, they look at 8 other types of (mostly) illegal activities, which are also extremely difficult to measure. Then they notice that 4 of these 8 activities involve between 1% and 3% of GDP.

PWC have done the following. They start with the admission that they have no idea how to directly estimate the losses from trade secret theft. Instead, they look at 8 other types of (mostly) illegal activities, which are also extremely difficult to measure. Then they notice that 4 of these 8 activities involve between 1% and 3% of GDP.

Where to begin?

1. Why assume that the estimates for other activities are accurate?

2. Why assume that the loss from trade secret theft is typical of other activities?

3. If this is indeed the right method, then why not include other illegal sectors, such as the smuggling of tropical birds into the US? Why just pick the large activities?

4. Why assume that the size of an illegal activity like drug smuggling is a proxy for the cost of that activity to society?

5. Why include R&D, which is 2.7% of GDP? It’s not an illegal activity. And does it seem plausible that the losses from trade secret theft exceed the total amount spent on R&D? But the high end of their range is 3% of GDP. As an analogy, is it plausible that losses from shoplifting exceed total revenue for retail sales?

6. Notice that the most similar activity (software piracy) has a far smaller cost than the other 7.

The bottom line is that there is no there there. No matter where you look, there is no reliable estimate of the cost of IP theft to the US (much less the cost in foregone utility to the entire world.)

In fairness, it’s quite plausible that the losses in this area are pretty large in dollar terms, certainly in the billions, or even tens of billions. But that view is not based on any of these near worthless studies; rather it’s my intuition given two facts:

1. Information is a more and more central part of the global economy. Commodities are an increasingly small share of the economy.

2. Information is easy to steal, and can be almost costlessly replicated.

Given these facts, IP theft will almost inevitably be an increasing problem. Not just with China, but with India and many other countries as well. (Recall the slogan, “information wants to be free”) For fans of IP protection, this theft is a valid concern.

But this perspective also suggests that as with drug smuggling, the problem will be almost impossible to stop. Consider the 2017 US government report’s discussion of China’s new communication satellite technology:

Perhaps the most recent case is China’s development of the Micius satellite, considered the world’s first quantum communications satellite, which China launched into orbit in 2016. Scientists at national laboratories and academic institutions around the world have been working on developing technology based on quantum mechanics to create a communications system that is considered to be completely secure from penetration. China is eager to develop this technology to protect its own communications from potential adversaries like the United States. However, perhaps ironically, China was able to develop quantum communications technology ahead of its rivals by incorporating their research findings. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Pan Jianwei, the physicist leading the project, was quoted saying, “We’ve taken all the good technology from labs around the world, absorbed it and brought it back.” This may be just an innocent quip about how scientists share their basic research findings with one another across borders. However, it has been demonstrated that the Chinese government systematically collects information and secrets from abroad to further its technology development goals, as illustrated by the cases discussed above.

This anecdote reveals more than the US government might have intended. It suggests that it will be almost impossible to prevent scientific and technical information from rapidly spreading around the world. The US should still crack down on IP thieves on a case-by-case basis, when they are caught, but we should not assume that this “war” is any more winnable than the drug war. Our pharma companies have basically accepted the fact that they are innovating for the high price American market, and the Europeans and Canadians will (legally) free ride. Our other companies need to accept that there will be a lot of (illegal) free riding in IP intensive products, and there’s only so much we can do about it when it occurs in other countries. Starting a trade war is a particularly inappropriate response.

I’m going to end with a comment left by Dallas Weaver after an earlier post on this topic:

You can divide IP into “real deep knowledge based IP” such as detailed scientific inventions and “fluff stuff” like “mickey mouse” or the business methods or “single click” IP. The latter is obvious and easy to “borrow” and the owner could and do object. I don’t care that much as the outcome is usually just rent-seeking with little contribution to humanity.

However, in the case of “real IP”, if you don’t have the knowledge base you can’t even steal it. You could give the detailed IP for the F-35 to all the countries in the world and only a very few could, even, in theory, make the plane. You can’t steal what you don’t understand.

If you have the ability to steal and utilize “real IP”, you also have the ability to create your own inventions. Why copy the obsolete designs of others rather than creating improvements. If you copy, you are always behind the curve.

Modern technology is so complex that the associated IP is all about people who understand the technology and China produces more STEM graduates in two weeks than we do in a year. Guess who will win the real IP game? Meanwhile, we demand that the new Ph.D. STEM graduates from our universities who are from China go home after graduation.

Most of the discussions about IP theft are by people who don’t have a strong enough STEM background to really understand what they are talking about. Even Tyler with his deep understanding of economics doesn’t understand that the “tree of knowledge” is producing more fruit than ever in history, but to reach it requires “standing on the shoulders of giants”.

To even be able to stand on the shoulder of giants requires being able to read primary references in the area and I would like to drop the challenge to the readers to pick up the Reports section of Science Magazine (AAAS Journal) and see how many refereed articles they could read and understand. When you stand on these shoulders you can see tons of what appears from your lofty perspective “low hanging fruit” for the picking.

PS. I’m pretty sure that Tyler does understand the amazing fruits produced by the “tree of knowledge”, but I thought his comment made some interesting points.

PPS. I have a related post at Econlog.