Identifying monetary policy shocks

People generally visualize monetary shocks as a univariate phenomenon, perhaps a change in the short-term interest rate, or a change in the monetary base. Up or down.

Over at Econlog, I recently argued that monetary shocks are a multivariate phenomenon. For example, a monetary shock might impact both the spot exchange rate and the forward exchange rate.

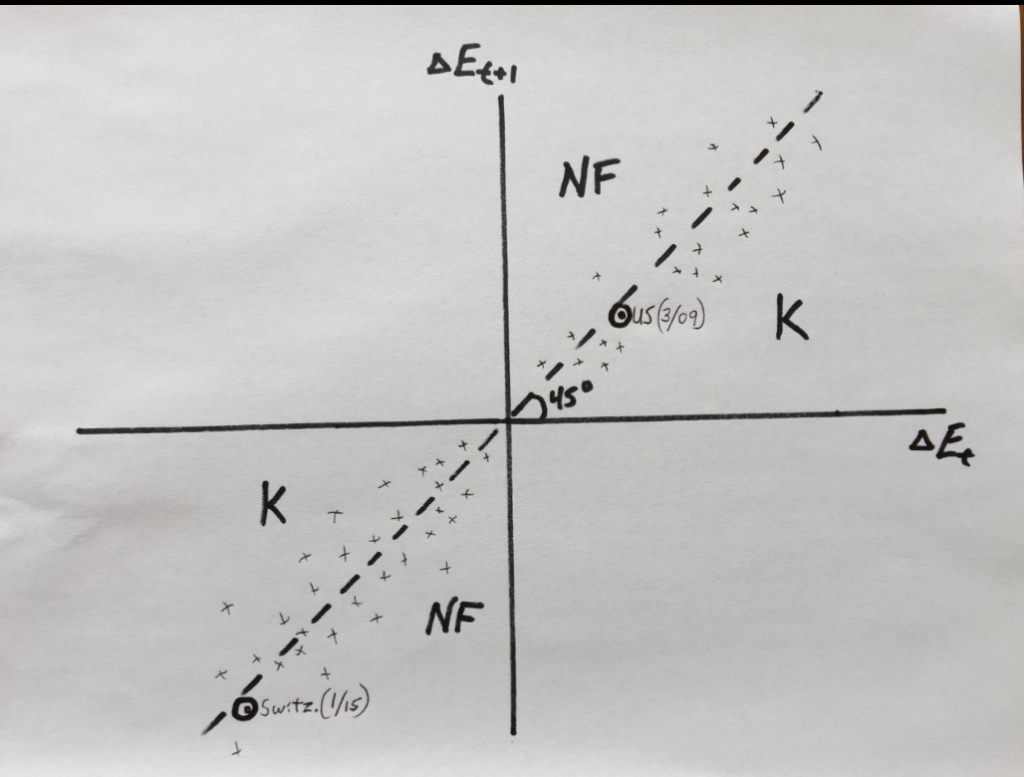

Here I’ll present a graph that illustrates various possible monetary shocks. I define Et at the spot price of foreign currency. Thus if Et gets bigger, then the domestic currency depreciates, and if Et gets smaller than the domestic currency appreciates.

In the graph below, the vertical axis shows the change in the one year forward exchange rate (Et+1), while the horizontal axis shows the change in the spot exchange rate (Et). Each point the response of forex markets to an important monetary policy announcement:

The galaxy of points in the upper right quadrant represent expansionary monetary shocks, which cause the currency to depreciate in both the spot and forward markets, that is, “E” gets larger. I provide an example of when the US announced QE1 on March 18, 2009.

The galaxy of points in the lower left quadrant are contractionary monetary shocks, such as the Swiss decision to let the franc float (appreciate) in January 2015.

You’ll notice that I also provided a 45 degree line, which shows whether the spot or the forward exchange rate responds more strongly to the monetary shock. Does it matter whether points lie slightly above or slightly below that 45 degree line? I’d say almost certainly not, but 99% of economists probably disagree with me.

If the spot rate moves by more than the forward rate, as in the March 2009 example, then nominal interest rates will fall with expansionary policy and rise with contractionary policy. If the spot rate moves by less than the forward rate, as in the January 2015 example, then nominal interest rates will rise with expansionary policy and fall with contractionary policy.

The impact of policy doesn’t depend on whether interest rates rise or fall, it depends on whether the exchange rate rises or falls. It doesn’t much matter whether you are slightly above or below the dotted line, it matters whether you are in the upper right quadrant or the lower left quadrant.

Keynesians and NeoFisherians don’t agree with me. Keynesians thinks lower interest rates are expansionary. They assume that monetary shocks lie in areas “K”, and affect spot exchange rates by more than forward rates (Dornbusch overshooting). NeoFisherians assume lower rates are contractionary. They assume that monetary shocks lie in areas “NF”, causing forward exchange rates to move more than spot rates.

Actually, the shocks occur in both areas, but movements in interest rates are inconsequential epiphenomena to the real action, the way that monetary shocks impact spot and future exchange rates, or better yet NGDP futures prices.

In January 2015, the Swiss franc suddenly rose more than 10% in response to a monetary shock. I don’t have forward exchange rate data, but I believe the forward Swiss franc appreciated about 1/4% more than the spot rate, say 10.25% instead of 10%. That’s because Swiss interest rates fell about 1/4%.

In March 2009, the US dollar suddenly fell about 4% on the announcement of QE1. Because one year T-bill yields fell about 11 basis points on the news, the forward rate might have only fallen 3.89%, vs. 4% for the spot rate (all figures in this post are rough estimates.)

If you believe that interest rates are the essence of monetary policy, then you believe that the fact that forward rates changed slightly more or less than spot rates is far more important than the fact that both spot and forward rates moved in the same direction. That’s crazy.

A Keynesian might view both the 2009 US shock and the 2015 Swiss shock as expansionary, as rates fell in both cases. A NeoFisherian might view them both as contractionary for the same reason. In contrast, when I see the dollar plunge 4% and the franc surge 10% after major monetary policy announcements, I see tighter money in Switzerland and easier money in the US. Judging by the co-movements in the various stock markets, I suspect investors agree with me.

Just to be clear, I don’t view exchange rate movements as being “monetary policy”, just a better policy indicator than interest rate movements. More specifically, I believe that by looking at exchange rate movements immediately after a major money announcement we can reasonably infer whether the monetary shock was expansionary or contractionary. Of course, exchange rates also move during periods when there is no monetary shock, for a variety of other reasons. Those movements are no “monetary policy”.

PS. You could do the same exercise for change in the “spot” money supply and change in the 10-year forward expected money supply. But again, NGDP futures prices are best.

PS. I have a new article at The Hill, which points out that the Fed is not “monetizing the debt”.