There’s a lot of discussion about whether Britain will have a recession as a result of Brexit.

There has been a pronounced tone-change among UK economics analysts since the EU Referendum: They are in unanimous agreement that the UK will sink into recession in the second half of this year.

They disagree only on the details and depth.

Call it the Silence of the Bulls: no one — literally, no one — is making a bullish case for the post-Brexit economy.

That is what is so scary about this recession. Usually, analysts and economists like to hedge their bets. Their opinions are spread over a range, with outright disagreements. They talk about “the risk” of something happening; they don’t say “this will happen.”

But right now everyone is saying the same thing. Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Robert Wood put out a note last week whose title says it all: “It’s not looking good.”

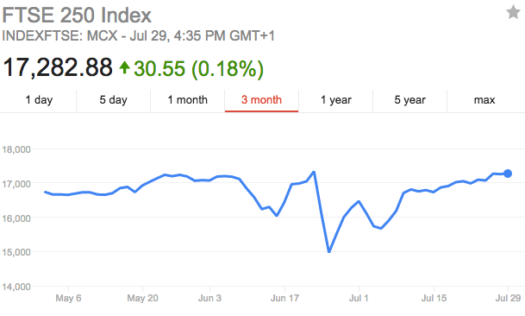

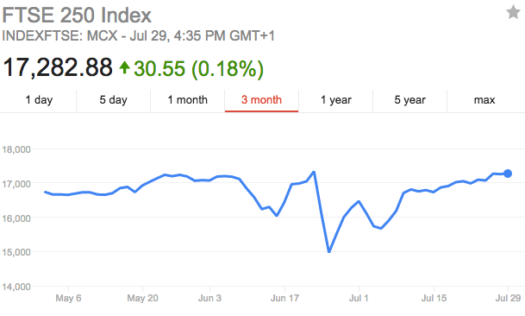

There is one glimmer of hope, the FTSE 250 stock index has fully recovered from the Brexit shock.

But there are two considerations that cut in the other direction. First, although the FTSE 250 is supposed to be a “domestic” stock index, unlike the multinational dominated FTSE 100, it still has a substantial exposure to international corporations:

But there are two considerations that cut in the other direction. First, although the FTSE 250 is supposed to be a “domestic” stock index, unlike the multinational dominated FTSE 100, it still has a substantial exposure to international corporations:

As financial markets approach the relatively quiet trading month of August, investors appear equally equivocal about the country’s prospects, in spite of this week’s surprise rebound in the FTSE 250 stock index — seen as a barometer of domestic UK companies — to pre-referendum levels.

Tempting as it is to read the FTSE 250’s rise as proof that all is well, Garfield Kiff, UK fund manager at M&G, cautions that the advance hides a less positive story.

“Put simply, despite the steady aggregate numbers, the stock market has concluded the UK is heading for a sharp economic slowdown,” he says.

The revival of the FTSE 250 looks like a vote of confidence for UK plc, but within the index there has been a clear divergence between the outperformers, which have been largely overseas earners, and domestic businesses such as housebuilders, retailers, and challenger banks.

In addition, British long term interest rates have fallen sharply since Brexit, thus even if future profits are expected to be lower, those profits are being discounted at a lower interest rate. So maybe the drop in the pound and lower bond yields are masking weaker growth expectations.

Or maybe all the pundits are wrong. After all, recessions are really hard to predict, especially those that involve substantial increases in unemployment. It will be an interesting 6 months, as we await the impact of an unusually large “uncertainty shock.” I’m on record as being somewhat agnostic on this issue, but to avoid being called a coward I have forecasted a 50 basis point increase in the UK unemployment rate. You might call that a “mini-recession”, or a “phony recession”. My hunch is that employment will hold up better than RGDP.

I was also surprised when the BoE did not move at its first meeting after the Brexit vote:

Markets were wrongfooted on July 14 when the Monetary Policy Committee voted 8-1 to leave policy unchanged. But the minutes of that meeting said “most members . . . expect monetary policy to be loosened in August”, leading market participants to believe with near certainty that action will come on Thursday.

The BoE’s forecasts and policy decision will have to be made in the absence of hard data on how the vote has affected the economy — most of which will not be published until September. In deciding what action to take, the MPC will weigh up the risk of not doing enough against the risk of depleting its limited firepower before knowing exactly what is required.

Hmm, I wonder what sort of futures market would allow the BoE to avoid waiting until September to respond to a shock that occurred in June? The FT article also speculates that the BoE will lower its growth forecast to roughly zero:

The Bank of England will this week downgrade its growth forecasts following the vote to leave the EU and explain what action it will take in response.

Governor Mark Carney said before the referendum that a Leave vote could result in a “technical recession” — two quarters in a row of the economy shrinking — and Thursday’s announcements will reveal whether or not policymakers think this is the most likely outcome. Growth forecasts are expected to be cut close to, and perhaps below, zero.

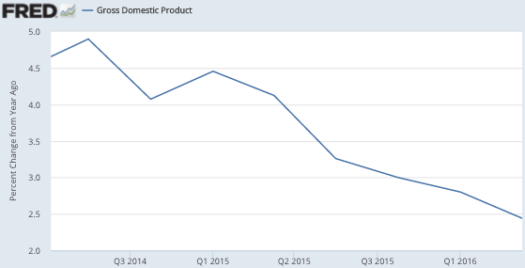

The IMF has a more specific forecast:

The International Monetary Fund has already knocked 0.2 percentage points off its forecast for growth in 2016 since the referendum, and 1 percentage point off for 2017.

That’s both very large and very small, depending on one’s perspective. It’s very large in the sense that it’s quite rare for a single political action to immediately chop so much off the consensus near-term growth forecast. Even electing Trump would probably have only a trivial impact on growth forecasts. And yet it’s small in the sense that the IMF prediction would probably result in only a very small rise in unemployment. Indeed it looks more like Japan’s three recent “phony recessions, or the UK phony recession from a few years back (when unemployment did not rise), than it does like the actual recessions of 2008-09, when unemployment rose sharply in Japan and Britain.

There are also hints that the BoE will lean a bit in the NGDP targeting direction:

Most independent forecasters predict the recent depreciation of sterling will push inflation up to about 3 per cent next year — well above the BoE’s 2 per cent target. But the MPC is expected to look through this and focus instead on stabilising medium-term output.

However, I’d caution readers that the higher CPI inflation may come from the weaker pound, and that the GDP deflator may not show a similar increase. Indeed I still expect NGDP growth to slow substantially.

PS. Over at Econlog I look at Brexit’s near-term impact from a political angle, which is a much more depressing story.