I’m choosing Japan for this post, but it could refer to almost any developed country.

I would argue that the answer to the question in the title depends on how you define “life”:

Definition A: The total utility of the typical life.

Definition B: The average flow of human utility in a typical year.

Economists usually think in terms of definition A, even though one could argue that strict application of our widely used utilitarian framework implies definition B is more appropriate. (Or even another definition, total flow of utility.)

Below is a typical picture of Japanese  life in the 1950s, along with a more recent picture, which shows what a typical day in Japan might look like during the 2050s. In which of these two pictures are “living standards” higher?

life in the 1950s, along with a more recent picture, which shows what a typical day in Japan might look like during the 2050s. In which of these two pictures are “living standards” higher?

Now you may complain that I’m comparing apples and oranges, that of course life is more fun when you are young than when you are elderly. And that’s true, but I’d also argue that these two pictures fit my definition B of “life”. In each case, I’m showing the typical experience of Japanese life during a given day, or even a given year.

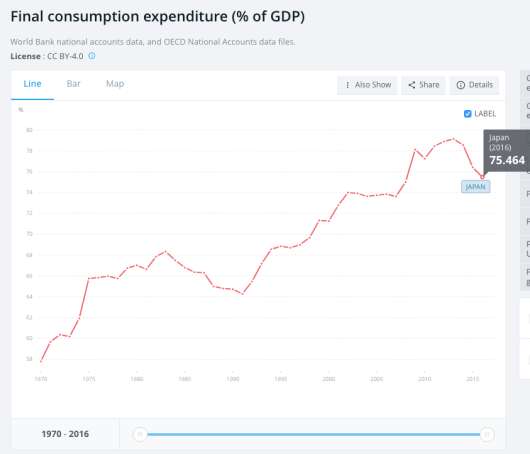

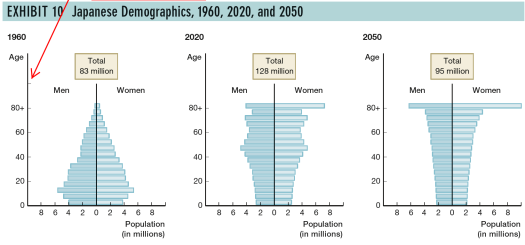

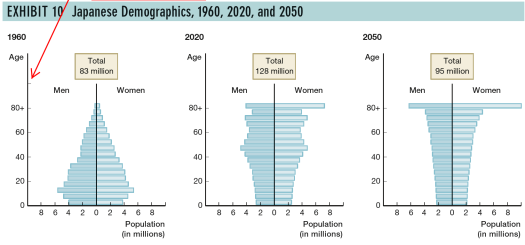

Consider the population distributions, by age for Japan in 1960, 2020 and 2050:

You can see that during the 1950s, life in Japan was mostly young life. During the 2050s, life in Japan will be mostly old life. In my previous post I argued that I’d gladly accept a much lower income to have the health and energy I had at age 31, rather than my current 62.

You can see that during the 1950s, life in Japan was mostly young life. During the 2050s, life in Japan will be mostly old life. In my previous post I argued that I’d gladly accept a much lower income to have the health and energy I had at age 31, rather than my current 62.

Just to be clear, I’m not a nihilist arguing that Japan’s amazing economic progress since the 1950s has been of no value. Living standards in material terms really are vastly higher. Not only are the Japanese much richer, they also live much longer. Nor am I arguing for a natalist policy to boost birthrates—I see no obvious market failure that calls for government interference. On the other hand, I’m not denying that a natalist policy might be beneficial, just that I haven’t yet seen any convincing arguments for interfering with people’s personal decisions on having children. So I don’t have any sort of agenda here, other than to make people think about what it means for life to be “better” than in the past.

Of course all this hinges on my preference for definition B of “life”. Most people probably think in terms of definition A, and hence would not be at all bothered by these trends, as long as the average complete life is better than before. My “flow approach” partly fits in with my denial of personal identity. I think of life as a series of experiences, and I think of “me” as being a completely different person from the “me” at age 8. Japan in the 1950s had a big flow of “young life”.

I’m so agnostic about all of this that I’m not even sure younger people really are happier. Happiness research doesn’t necessarily support this claim, even though we almost all instinctively feel that we’d like to be younger. Think about the vast industry for beauty products to make people look younger. Or “health clubs”. But maybe our worship of youth is all just looking through rose-tinted glasses.

BTW, the Japanese population pyramid from 1960 is roughly how things looked throughout most of human history, almost everywhere in the world. It’s the new distribution that is uncharted territory. If youth really does equate with happiness, how do we compare life in Mali and Niger, with life in Japan? Also, because poor countries typically have higher birth rates, and because birth rates fall as countries get richer, Japan’s birthrate cannot be increased by economic growth, no matter how many stories you read about modern East Asian families being unable to “afford” more than one child. Singapore is twice as rich as Japan, and has an even lower birth rate. Crazy rich Asians!

PS. The little girl on the left didn’t have an iPhone. I’m old enough to remember just how sad life was back then. Young people today can’t even imagine.

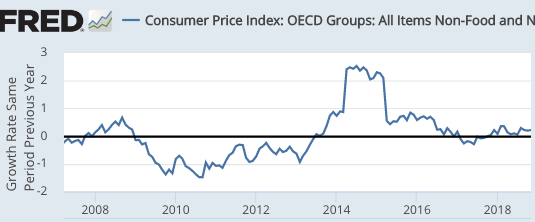

And growth in the Eurozone is slowing as we go into 2019.

And growth in the Eurozone is slowing as we go into 2019. And growth in Japan is also slowing.

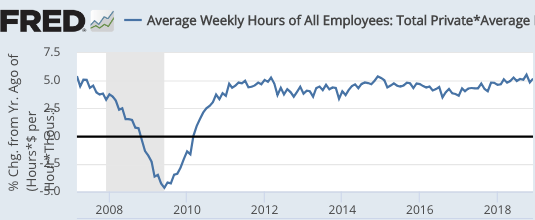

And growth in Japan is also slowing. This is what I’ve been advocating as a long run policy ever since I started blogging in early 2009. However I would have liked to have seen faster “catch-up” growth in the early years of the recovery. Even so, this is a good sign. If they can keep roughly 4% growth going forward then . . . . we win.

This is what I’ve been advocating as a long run policy ever since I started blogging in early 2009. However I would have liked to have seen faster “catch-up” growth in the early years of the recovery. Even so, this is a good sign. If they can keep roughly 4% growth going forward then . . . . we win.