Martin Feldstein on Fed policy

In a new WSJ piece, Martin Feldstein calls for higher interest rates. I don’t necessarily disagree with the need for somewhat higher interest rates, although I think we need to be very careful not to tighten policy too much. But I do disagree with his reasoning:

But controlling inflation isn’t the primary reason for the Fed to keep raising the short-term interest rate. Rather, raising the rate when the economy is strong will give the Fed room to respond to the next economic downturn with a significant reduction.

This is wrong. Raising interest rates reduces the Wicksellian equilibrium interest rate. That gives the Fed less room to cut rates in the future. The Fed does monetary stimulus by cutting rates below the equilibrium rate. The lower the equilibrium rate, the less room there is to use conventional monetary stimulus.

That downturn is almost surely on its way. The likeliest cause would be a collapse in the high asset prices that have been created by the exceptionally relaxed monetary policy of the past decade.

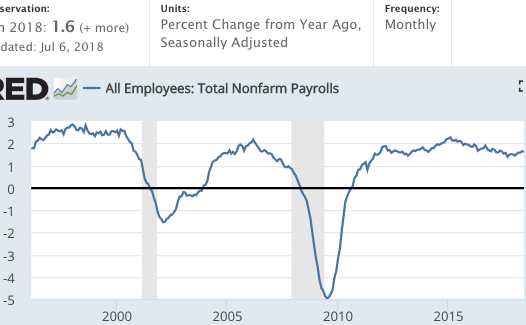

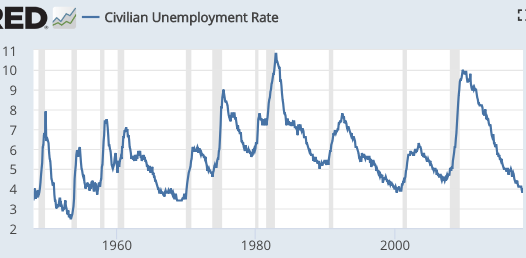

This is wrong. Downturns cannot be forecast. Even if they could, they are not caused by high asset prices; they are caused by tight money. And the recent high asset prices are not caused by easy money, because money has not been easy over the past decade.

It’s too late to avoid an asset bubble: Equity prices already have risen far above the historical trend. The price/earnings ratio of the S&P 500 is now more than 50% higher than the all-time average, sitting at a level reached only three times in the past century. Commercial real-estate prices also are extremely high by historical standards.

This is wrong—bubbles do not exist. Past P/E ratios are not very useful in predicting asset prices. If they were, P/E mutual funds would outperform ordinary funds. Robert Shiller likes to use P/E ratios, and made some predictions about stock prices in 1996 and 2011. The predictions did not turn out well. Real estate prices are skewed by NIMBYism, and unusually low interest rates relative to NGDP growth.

The inevitable return of these asset prices to their historical norms is likely to cause a sharp decline in household wealth and in the rate of investment in commercial real estate. If the P/E ratio returns to its historical average, the fall in share prices will amount to a $9 trillion loss across all U.S. households.

Inevitable? If Martin Feldstein wants me to sign a contract to buy San Francisco property in 5, 10 or 15 years, at “historical norms” plus 10%, I’ll sign tomorrow. Show me where the dotted line is. Ditto for stocks. I’ll buy stocks right now, to be delivered in 10 years, at “historical norms” plus 10%. Does Feldstein want to sell those assets at that price? After all, if prices fall to historical norms he’d make a 10% profit. Of course I’m not being serious—if I were in his shoes I wouldn’t want to waste time doing a deal with me; my point is for readers to think more deeply about what stuff is worth.

Large drops in household wealth are usually accompanied by declines in consumer spending equal to about 4% of the wealth drop. That rule of thumb implies that a $9 trillion drop in the value of equities would reduce consumer spending by about 2% of gross domestic product—enough to push the economy into recession. The fall in the value of commercial real estate would add to the decline of demand. And with consumer spending down sharply, businesses would cut back on their investment and hiring.

Drops in wealth do not necessarily cause a drop in spending; it depends on why wealth changes. The stock market crash of 1987 did not impact consumer spending. Where the two move together, it’s usually because a third factor such as the business cycle is causing both. But if the Fed keeps NGDP growing at a steady rate (as in 1987), then an asset price drop is not likely to have much impact on consumer spending. And even if consumer spending does drop, it’s not likely to push the economy into recession as long as the Fed keeps NGDP growing at a steady rate. What matters is not consumer spending, it’s aggregate spending.

But significant monetary stimulus would be impossible to achieve if the short-term interest rate remains at the current 1.75%. And there is less room than ever for fiscal stimulus, as annual deficits will exceed $1 trillion by 2020 and federal debt will be greater than 100% of GDP by the end of the decade.

This is half wrong. As Frederic Mishkin used to point out in his best selling monetary economics textbook, monetary policy remains “highly effective” at near zero interest rates. However, Feldstein is right about fiscal policy.

That’s why it’s important for the Fed to raise the federal-funds rate to 4% over the next two years, which would allow it to cut the rate by at least three points when the next recession begins. Such a rate reduction might not be enough to prevent a recession within the next two years, but it would maximize the Fed’s positive influence on the economy.

It would be a huge mistake to raise rates so sharply (unless the economy got much stronger than I current expect.) This might well trigger a severe recession, and in that case the equilibrium interest rate would fall sharply. The Fed would actually have less room to cuts rates than they do right now, not more.

Feldstein’s views are very popular among conservative economists. But I’m heartened to see that many younger economists and grad students are increasingly moving toward the market monetarist perspective, as events consistently back our interpretation and discredit the standard conservative view. We are currently behind, but we’ll win in the long run.

PS. I can’t even imagine what Feldstein would make of the past 27 years in Australia—they must be about to enter an enormous, humongous, stupendous, monumental, colossal, gigantic, titanic, vast, huge, bigly, Great Great Great Depression. Check out David Beckworth’s post on house prices and debt in Australia, compared to the US.

HT: Stephen Kirchner