Was the so-called “monetarist experiment” ever tried?

Jim Glass left this response to my (italicized) claim:

1. The Fed said it would start targeting the money supply, but it did not do so …. 1979-82 told us essentially nothing about the long run effect of money supply targeting. It wasn’t even tried.

I don’t understand you here. Certainly money supply targeting wasn’t tried over a long run, so one can’t see any long-run effect of it. But why do you say money supply targeting wasn’t adopted at all?

Volcker in his 1992 memoir “Changing Fortunes” explained why the Fed in 1981 had to change policy to money supply targeting from interest rate targeting, and went into considerable detail about the political resistance from the Reagan Administration that he had to overcome to do it, and the political ploys he used to do so. I don’t see why he’d make up such a detailed story about something that never happened.

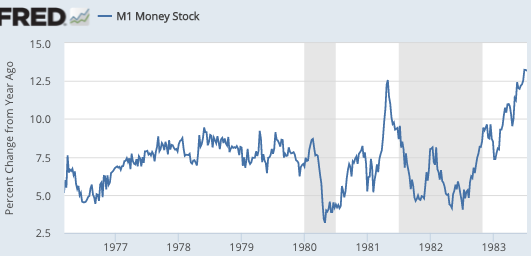

Plus, looking at the M1 numbers for the period from Fred, one sees that after rising steadily pretty much from beginning of time, M1 peaked at $429 billion on 4/20/81, three months before the start of the recession, then went down a little bit, then bounced down a tiny tad and back up again repeatedly to hit pretty much exactly $429b again on 7/6, 8/10, and 10/12 thru 10/26 without ever going at all over $429b (or going below $423b). So on the dates three months before the recession started and then three months after it started, M1 was $429b, exactly unchanged. If the money supply wasn’t being targeted during that period, all those $429b numbers are a heck of a coincidence.

It’s certainly possible that the Fed was paying more attention to M1 than before. I agree with that claim. But there can be no dispute that they did not adopt Friedman’s proposal of a steady 4% growth rate in the money supply. Indeed money growth actually became much less stable during 1979-82, which shows that Volcker moved policy even further away from Friedman’s ideal. Now of course in a different sense you could say monetarism was adopted, as he used a tight money policy to control inflation. That policy was a success.

But a money growth rule? It’s never even been tried. (And I hope it never will be tried, as it’s probably a lousy idea.)

Tags:

27. September 2016 at 07:15

Wasn’t M2 Friedman’s preferred metric? In any case, I do think M1 has a more direct effect on NGDP than M2.

27. September 2016 at 10:02

Strange post by Sumner, who spends an entire post on a silly issue of semantics. I hope Sumner posts on Paul Romer’s recent critique of the entire economics profession: hero worship, ad hominem attacks, and reliance on unmeasureable, metaphysical variables (“Wickesian interest rate”, “natural interest rate”, “slope of SRAS, SRAD curves (which Sumner thinks –his prior–supports money neutrality”, NAIRU, just to name a few). In a nutshell, it’s this blog. E-CON-omics is not hard science. Art, yes. Social ‘science’, yes. Politics, yes. But science? No.

27. September 2016 at 10:13

Scott,

I believe pretty strongly that the Fed was targeting money supply growth. Barnett answers this question in his book. I feel like you have to be quite the conspiracy theorist to believe otherwise. Sure it was no long run experiment, but mainly because velocity and demand were acting erratic. I would agree that these money measures are ridiculous and the cause for velocity instability. I also think you’re right. Even if velocity is stable why not adopt NGDP targeting. Maybe through some Ireland and Belongia framework (using Divisia).

My question is if you forgot a money supply growth rule in favor of NGDP targeting how do we know our RGDP hasn’t been structurally changed and our inflation target is bad. I want to say I don’t think potential is lower but a lot of smart people do. How do we recolonize long run potential isn’t lower (particularly in a long slow recovery)?

First time poster long time reader. Great blog!

27. September 2016 at 10:41

Harding, His views changed over time.

Ray, I already posted on it.

Mike, You said:

“I believe pretty strongly that the Fed was targeting money supply growth. Barnett answers this question in his book. I feel like you have to be quite the conspiracy theorist to believe otherwise.”

I think we are talking past each other. Yes, they were using M1 as a intermediate target. My point was different, they did not adopt Friedman’s proposal to keep money growth stable. You can see that in the graph I provide. It would be analogous to the distinction between pegging the fed funds rate and targeting the fed funds rate. With a target, the rate can change from one meeting to the next.

Friedman was proposing pegging the M1 growth rate at 4% per year. They did not do that, not even close. So his policy was never tried. I don’t think this is controversial—Friedman certainly didn’t believe that the Fed adopted his policy proposal.

On your second point, it makes no difference what happens to trend RGDP, if you target NGDP. And btw, the trend RGDP growth rate has fallen, there’s almost no doubt about that anymore.

27. September 2016 at 13:36

“M1 peaked at $429 billion on 4/20/81”

——————–

N-gNp peaked (right before that money figure), at 19.1 percent in the 1st qtr. of 1981. The gNp-deflator peaked at 10 percent during the same qtr. That was the latent (distributed lag) effect of the excessive growth in the money stock which occurred in 1980 (whence Volcker advised us on Oct. 6, 1979 to “watch the money stock”) – which later exploded at a 20 percent annual rate of change after his pronouncement.

An understanding of the temporary and longer term effects of money supply growth reveals why the tight money policy initiated in February brought about a continued upsurge in interest rates. But it had the longer term effect of bringing inflation and interest rates down, while the easy money policy initiated in May 1980 provided a temporary impetus to the decline in interest rates, but subsequently unleased hell (as the Fed acted irresponsibly and literally lost control of the money stock).

“three months before the start of the recession”

And that was the 2nd recession (after Jul. 1981 – Nov. 1982), right after the first one in (Jan. 1980-Jul. 1980). No, Volcker didn’t tighten. He didn’t need to tighten then, Paul Volcker couldn’t correct his mistakes at that point. The damage he created all by himself was already done. His “stop – go” monetary mis-management had already destabilized the economic path. Monetarism involves more than watching the aggregates, it also involves controlling them properly.

At that apex (all time high in nominal interest rates), there was no one left who wanted to borrow. I.e., Volcker simply let the economy burn itself out.

“I don’t see why he’d make up such a detailed story about something that never happened.”

What people should realize is that Paul Volcker is no icon, he is a blatant liar. And it wasn’t the first time. Paul Volcker, appearing before the House Domestic Monetary Policy Subcommittee answered them, in response to a question as to why the Fed had supplied an excessive volume of legal reserves to the member banks in the third quarter 1980 (annual rate of increase 13.2%), Volcker’s defense was that there are two types of legal reserves: 1) borrowed (reserves obtained by the banks through the Federal Reserve Bank discount windows), and 2) non-borrowed (reserves supplied the banking system consequent to open market purchases).

He advised the Congressmen to watch the non-borrowed reserves — “Watch what we do on our own initiative.” The Chairman further added — “Relatively large borrowing (by the banks from the Fed) exerts a lot of restraint.”

That was of course, economic nonsense. One dollar of borrowed reserves provides the same legal-economic base for the expansion of the money stock as one dollar of non-borrowed reserves. The fact that advances had to be repaid in 15 days was immaterial. A new advance could be obtained, or the borrowing bank replaced by other borrowing banks. The importance of controlling borrowed reserves was indicated by the fact that at times nearly 10% of all legal reserves were borrowed then.

And that was before the discount rate was made a penalty rate in Jan 2003. And the fed funds “bracket racket” was simply widened, not eliminated.

Monetarism has never been tried.

27. September 2016 at 16:30

As I have noted before, there is an odd inconsistency in Milton Friedman’s 1968 Presidential Address. He criticises relying on a statistical regularity because people will adjust their behaviour. He then suggests relying on a statistical regularity (the stability of V). So, I agree, probably a terrible idea.

27. September 2016 at 16:53

Scott, I was wondering if you could comment on Roger Farmer’s new post today.

http://www.rogerfarmer.com/rogerfarmerblog/2016/9/27/the-liquidity-trap-and-how-to-escape-it-time-for-a-new-approach

Thanks!

27. September 2016 at 17:25

Remunerating excess reserve balances, IBDDs, has emasculated the Fed’s “open market power”, viz., the Central Bank’s sovereign right to promulgate the creation of new money and credit: at once and ex-nihilo.

I.e., “pushing on a string” only applied prior to the nominal legal adherence to the fallacious “Real Bills Doctrine” which was terminated in 1932 – due to a paucity of eligible (hopelessly impaired), commercial and agricultural paper for the 12 District Reserve bank’s discounting purposes.

Gov’ts weren’t made eligible until the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, or U.S. Banking Act of 1933, with the (with further liberalization of the eligible collateral accepted provided in the Banking Act of 1935 – “secured to the satisfaction of the Federal Reserve Bank”).

Historically, coming out of a recession, the commercial banks, today’s DFIs, initially bought highly liquid, short-term assets, pending a more profitable disposition of their legal and economic lending capacity, i.e., between 1942 and Oct 1, 2008, the CBs remained fully “lent up”, the CBs minimized their non-earning assets, their interbank demand deposits, IBDDs, or excess reserves.

Indeed, in direct contrast to the GR, excess reserves balances actually fell during some economic recessions, 12/69 – 11/70; 11/73 – 3/75; 1/80 – 7/80; 7/81 – 11/82 (i.e., until the S&L crisis).

Excess reserve balances never exceeded > $2b, and only for 1 month, in 1/91 (and not over $4b until 8/07, and then not exceeding that threshold until 9/08 (just before the payment of interest on excess reserve balances turned non-earning assets into commercial bank’s earning assets on 10/6/08).

The CBs always responded (by purchasing short-term securities), without delay – to any injection of excess reserve balances, i.e., to any excess lending capacity, by the Central bank.

I.e., the CB’s response was always self-correcting, or counter-cyclically (without Gov’t intervention), by expanding the money stock (buying securities, not necessarily making loans).

And today, in contrast to the Great Depression, there is a surfeit of eligible collateral (viz., considering our 19 trillion dollar federal debt). All that the Central bank has to do is isolate its counterparty and only purchase securities from the non-bank public (as buying from the banks only creates more IBDDs).

27. September 2016 at 17:41

The problem with AD, is that the 300 Ph.Ds. on the Fed’s research staff don’t know money from mud pie. M1 is increasingly overstated and IBDDs are understated since March 31st 1980.

Secular stagnation results from impounding savings within the commercial banking system. Impounding savings destroys NB money velocity (where savings and matched with real-investment outlets and are “put to work”). It is universally mis-understood. Commercial banks, from a system’s perspective, do not loan out existing deposits, saved or otherwise. The shift in bank-held savings is no longer offset by the demand curve moving to the right.

I.e., Professor Lester V. Chandler’s demand curve (thesis) was correct up until the saturation of financial innovation that occurred with the widespread introduction of ATS and NOW accounts in the 1st qtr. of 1981.

Henceforth money velocity, as ominously predicted by Dr. Leland J. Prichard, Ph.D, economics,

Chicago, 1933, in the May 1980 issue of IMTRAC, steadily declined. And the decline in Vt resulted in the deceleration in AD, and therefore produced an adverse impact on N-gDp. Long-term interest rates thus from that juncture, have parroted N-gDp growth.

28. September 2016 at 12:05

Lorenzo, Good point.

CA, Excellent, I’ll do a post, but not today–maybe tomorrow.

3. October 2016 at 23:47

Scott,

I take you for a China guy so I’m surprised you didn’t mention Taiwan, whose central bank has followed a Friedman k-percent rule targeting M2 since 1992. Since 1998 M2 growth has averaged a steady 5.2% and NGDP growth, 3.3%. Real growth has been shocked down – the dot-com bust, SARS – and up – China WTO dividend. The positive shock from the China WTO dividend produced a long period of GDP deflator deflation (-1.0% on average in 2002-08). The negative shock from the global financial crisis has swung that to 1.3% GDP deflator inflation. Puzzlingly, the swings in GDP deflator inflation haven’t affected CPI inflation, which has steady throughout at just over 1%.

Imo M2 targeting in Taiwan has delivered stable NGDP growth and low, steady CPI inflation.