Megan Greene on NGDP (forecast) targeting

This FT article by Megan Greene is a sort of breakthrough:

If they are serious about achieving their mandates more effectively, the Fed and ECB should consider other strategies.

One has been circulating for decades: target the sum of inflation and total real output, or nominal gross domestic product. With NGDP targeting, a central bank automatically lowers rates as output falls, to push up inflation. That eases real debt burdens and lowers real interest rates, helping to generate growth. As output rises, rates adjust higher to bring inflation down and maintain the target.

A potential obstacle is that NGDP is reported quarterly, with a lag. But NGDP could be reported more frequently and accurately if the Fed treated it as a priority. The Fed could also target the forecast of NGDP instead, which is reported in the monthly blue-chip economic indicators survey of business economists.

There have been plenty of other pundits calling for NGDP targeting, but this is the first one I recall that advocated a “target the forecast” approach. If forecasts are useful in monetary policy (and they are) then we obviously need to create a market-based NGDP forecast. Hypermind has actually done so, but we need to create a much more liquid NGDP futures market.

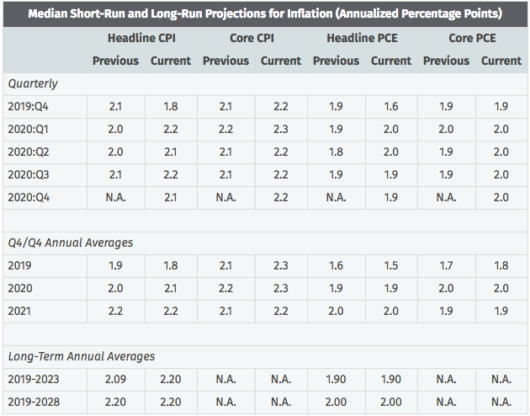

We cannot trust the consensus forecast of economists because they consistently forecast too high, just like the Fed itself:

It’s always around 1.9% to 2.0% in the out years—a major embarrassment for the profession. Trust markets, not economists.

PS. The 3-month/10-year Treasury spread recently inverted. As I pointed out a year ago, that doesn’t necessarily mean money is too tight or that a recession is imminent. But when combined with other indicators, it seems clear that money is currently a bit too tight.

Some of this relates to the coronavirus epidemic, which has a small chance of being a major problem for the global economy and a large chance of blowing over in a few months. The following analogy might be helpful:

Suppose you see a crazy guy load one bullet into the cylinder of a revolver. He puts the gun to his head and pulls the trigger. Nothing happens.

Would you say, “See, he made a wise decision, as nothing bad happened. He just had some fun playing Russian roulette.” Or would you say that even in retrospect his decision was foolish?

That’s sort of how I think about current Fed policy. I think there’s a 5/6 chance of no recession this year. But I still think it would be wise to cut the IOR rate, to further reduce that risk. I am disappointed by the Fed’s recent decision, and hope that they are monitoring events closely. There’s a real danger that they will fall behind the curve if the coronavirus crisis gets much worse. Indeed I think it likely they will fail to adopt a sufficiently expansionary policy in the event of a global pandemic.

If that happens, we can’t let them off the hook with excuses about unforeseen “shocks”. The markets are very clearly indicating RIGHT NOW that money is a bit too tight.

They’ve been warned. Fix it.

PS: I agree with this:

“The bond market is basically telling the Fed that it hasn’t done enough and will be called back to do more and that the longer they wait the more they will have to do,” said Michael Darda, market strategist at MKM Partners. “If the bond market thought Powell’s comments on wanting higher inflation were credible in his press conference, you wouldn’t have seen break-even inflation rates falling as they did.”

HT: David Beckworth