No, this is not a NeoFisherian post. I’m not claiming that a Fed policy that depresses interest rates is contractionary, I’m claiming lower interest rates are contractionary, ceteris paribus. And ceteris paribus in this case means for any given money stock. For simplicity, we’ll start with a simple model–no IOR— and then bring in IOR later. And in doing so I’ll answer a question a commenter asked me: Is talking about the effect of IOR an example of reasoning from a price change?

Let’s start with this identity:

M*V = P*Y

Where M is the base and V is base velocity. Now let’s build a model:

M*V(i) = P*Y

Since V is positively related to i, lower interest rates are contractionary, they reduce V and hence NGDP, AKA aggregate demand. Larry Summers once wrote an article (with Robert Barsky) pointing this out, but only for the gold standard period.

So why do people not named Summers and Sumner not know this? There are several reasons:

Sometimes, not always, reductions in interest rates are caused by an increase in the monetary base. (This was not the case in late 2007 and early 2008, but it is the case on some occasions.) When there is an expansionary monetary policy, specifically an exogenous increase in M, then when interest rates fall, V tends to fall by less than M rises. So the policy as a whole causes NGDP to rise, even as the specific impact of lower interest rates is to cause NGDP to fall.

2. Another problem is the Keynesian model, which hopelessly confuses the transmission mechanism. Any Keynesian model with currency that says low interest rates are expansionary is flat out wrong. That’s probably why economists were so confused by 2008. Many people confuse aggregate demand with consumption. Thus they think low rates encourage people to “spend” and that this somehow boosts AD and NGDP. But it doesn’t, at least not in the way they assume. If by “spend” you mean higher velocity, then yes, spending more boosts NGDP. But we’ve already seen that lower interest rates don’t boost velocity, rather they lower velocity.

Even worse, some assume that “spending” is the same as consumption, hence if low rates encourage people to save less and consume more, then AD will rise. This is reasoning from a price change on steroids! When you don’t spend you save, and saving goes into investment, which is also part of GDP. Now here’s were amateur Keynesians get hopelessly confused. They recall reading something about the paradox of thrift, about planned vs. actual saving, about the fact that an attempt to save more might depress NGDP, and that in the end people may fail to save more, and instead NGDP will fall. This is possible, but even if true it has no bearing on my claim that low rates are contractionary.

To see the problem with this analysis, consider the Keynesian explanations for increases in AD. One theory is that animal spirits propel businesses to invest more. Another is that consumer optimism propels consumers to spend more. Another is that fiscal policy becomes more expansionary, boosting the budget deficit. What do all three of these shocks have in common? In all three cases the shock leads to higher interest rates. (Use the S&I diagram to show this.) Yes, in all three cases the higher interest rates boost velocity, and hence ceteris paribus (i.e. fixed monetary base) the higher V leads to more NGDP. But that’s not an example of low rates boosting AD, it’s an example of some factor boosting AD, and also raising interest rates.

Again, I defy you to explain how low rates can boost NGDP, ceteris paribus. If you think you have an explanation, it’s probably something that confuses consumption with total spending on NGDP. An explanation that wrongly assumes the public’s desire to spend more on consumption, as a result of lower interest rates, is expansionary for NGDP. Yes, an exogenous change in M will often cause short term rates to move in the opposite direction, but how often do you see exogenous changes in M? If we were operating in a normal economy, with say 3% or 4% interest rates, and I told you rates would fall to zero in the next 12 months, would you predict a recession or boom? Obviously a recession. Yes, if the Fed perversely cut rates to zero in an otherwise stable economy, via fast growth in the base, that would be expansionary. But more than 100% of the expansionary impact would come from the rise in the base (hot potato effect), and less than zero from the lower rates.

There is simply no mechanism in macroeconomics where low rates actually CAUSE more NGDP. None. Nada. Lower rates reduce velocity, and that’s contractionary. It’s not about “spending”, unless by “spending” you mean velocity. If you mean “spending” vs. saving then you are hopelessly off track. You aren’t even in the right train station.

Now for the hard part. The Fed recently raised the fed funds rate, and did so without lowering the base. So am I claiming that the Fed’s decision was expansionary? No, but I wouldn’t blame you for seeing a contradiction here, especially if your last name is “Murphy.”

Suppose the Fed had raised the fed funds target, without raising IOR. What then? Then they would have had to reduce the monetary base enough to make the rate increase stick. How much? Fasten your seatbelts—by almost $3 trillion. That’s right, without IOR, to even get a measly quarter point increase, they would have had to withdraw almost the entire previous QE (except the part that went into currency held by the public.)

Instead the Fed did something else, they raised IOR. Even though IOR includes the term ‘interest,’ as part of its acronym, it actually has absolutely nothing to do with market interest rates as I’ve been discussing them so far. It’s better to think of IOR as a tax/subsidy scheme.

Previously I claimed that higher interest rates are expansionary. They are. But higher IOR really is contractionary. That’s why the New Keynesians love IOR so much. It helps make their false “non-monetary” models of the economy less false, indeed sort of truish. It really is true that higher IOR is contractionary. So why the difference? Let’s return to the simple model above. I said that model applied to a world of no IOR. If IOR exists, then the more general model is:

M*V(i – IOR) = P*Y

That is, velocity is positively related to the difference between the market interest rate and the interest rate on money. This gap is the opportunity cost of holding reserves. I wish there were no IOR, if only because it would make monetary analysis so much simpler.

In order to make monetary policy more contractionary, the Fed merely needs to shrink the gap between i and IOR. That reduces the opportunity cost of holding base money, which causes more demand for base money (as a share of NGDP), which is contractionary. Consider the weird situation we are in:

1. Almost everyone assumed higher rates were contractionary, but almost everyone was wrong.

2. Now IOR comes along, and higher IOR really is contractionary.

Now I fear that it will be even harder to slay the Keynesian dragon; the model now seems superficially even more plausible. If I was a conspiracy nut I’d think it was all a plot to make Woodford’s moneyless models appear more accurate.

To summarize, IOR is not really a market price, it’s a subsidy on base money, and negative IOR is a tax on base money. Just as it’s OK to reason from an increase in excise taxes on gasoline, it’s OK to reason from a change in IOR. (Of course you also need to consider other changes that are occurring in monetary policy, as is always the case.)

So if lower interest rates are not the reason that monetary stimulus is expansionary, then what is the reason? Why do more people want to go out and assume car loans when the Fed cuts interest rates via an easy money policy? Here’s why:

1. If the Fed lowers rates via an increase in the base, then more base money raises NGDP via the hot potato effect (AKA, laws of supply and demand). Interest rates play no role, indeed NGDP would rise by even more if rates (and velocity) didn’t fall.

2. The higher NGDP causes more hours to be worked, due to sticky nominal hourly wages.

3. More hours worked means more output and more real income.

4. Say’s Law says supply creates its own demand. So as workers and capitalists produce more output and earn more income, they go to car dealers to splurge with their sudden newfound wealth. Interest rates got nuthin to do with it. Saving (and investment) as a share of GDP actually rises during booms created by monetary stimulus. It’s not about “spending” (as in consumption), it’s about actual spending on C+I+G+NX, i.e. NGDP.

5. Of course all this happens simultaneously, as we live in a Ratex world.

PS. I’m begging you, don’t try to explain what you think is wrong with Say’s Law, unless you want me to be as insulting as possible in response.

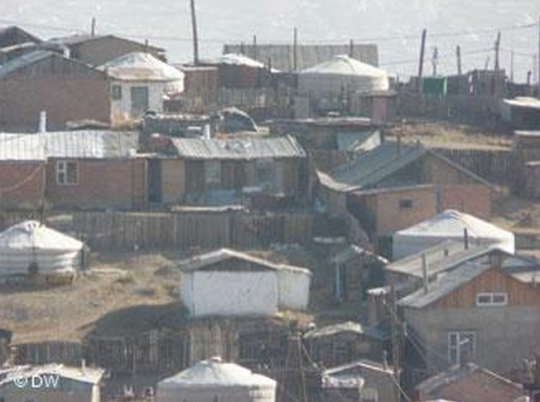

Fortunately, a mining boom has made Mongolia rich, and the peasants are flocking to the cities, and put up their yurts in shanty towns on the edge of Ulaanbaatar—which now has a majority of Mongolia’s population.

Fortunately, a mining boom has made Mongolia rich, and the peasants are flocking to the cities, and put up their yurts in shanty towns on the edge of Ulaanbaatar—which now has a majority of Mongolia’s population.