Bloomberg has a new article that attempts to explain what MMT is all about. It begins by quoting yours truly:

“MMT has constructed such a bizarre, illogical, convoluted way of thinking about macro that it’s almost impervious to attack,” Bentley University economist Scott Sumner claimed recently on his blog.

Their explanation begins as follows:

A good place to start is with a simple description that you can carry in your pocket: MMT proposes that a country with its own currency, such as the U.S., doesn’t have to worry about accumulating too much debt because it can always print more money to pay interest. So the only constraint on spending is inflation, which can break out if the public and private sectors spend too much at the same time. As long as there are enough workers and equipment to meet growing demand without igniting inflation, the government can spend what it needs to maintain employment and achieve goals such as halting climate change.

If you’ve absorbed that much, you’re already ahead of a lot of the critics.

Unfortunately, I’m not ahead of the critics, as I have no idea what that means. All I can ascertain is that they don’t think we need to worry about accumulating too much debt. I say that because they say we shouldn’t worry about accumulating too much debt. But is even that interpretation accurate? Not in the world of MMT:

Another misconception is that MMT says deficits never matter. On March 13 the University of Chicago Booth School of Business published a survey of prominent economists that misrepresented MMT that way, leaving out its understanding that too-big deficits can cause excessive inflation.

OK, so perhaps we do need to worry about accumulating too much debt, as it could lead to high inflation? I’m confused.

MMT also draws on the “functional finance” work of the Russian-born British economist Abba Lerner, who wrote in the 1940s that government should spend what’s required to achieve its goals, deficits be damned.

OK, so now deficits don’t matter anymore. Whatever you accuse the MMTers of saying, they can find a quote that says the exact opposite. Now you might argue that they’re only saying deficits don’t matter when they are directed toward “goals”, and we all know that the goals of progressive politicians are a clearly delineated highly scientific concept. “We need precisely $X trillion to meet our goals, and not a penny more. Any additional spending beyond $X trillion would exceed our “goals” and lead to inflation.” Is that the idea?

The article is packed full of puzzling claims:

Modern Monetary Theory says the world still hasn’t come to terms with the death of the gold standard in 1971, when President Richard Nixon declared that the dollar was no longer convertible into gold. In the modern era of “fiat” currency, MMT says, the U.S. and other big economies no longer need to worry about having enough gold to back their paper money, so they’re free to print however much they need.

I think mainstream economists understand that money is not backed by gold and that the central bank can technically print almost unlimited amounts (barring government restrictions). The debate is over the effects of doing this.

Unless they mean that some economists don’t understand that central banks always have enough “ammo” to hit their target. But do even MMTers understand that?

MMT claims to be the legitimate heir to the theories of Britain’s John Maynard Keynes, who created the field of macroeconomics during the Great Depression. Keynes coined the term “paradox of thrift.” His insight was that while any single household can dig itself out of a hole by cutting spending when its income falls, the economy as a whole cannot. One household’s spending is another’s income, so if everybody cuts back, no one gets paid.

Of course this is wrong, as even modern Keynesians recognize. The economy can reduce overspending by shifting resources from consumption toward saving/investment. The final sentence confuses “consumption” with “spending”, an EC101 level error. At an aggregate level, spending includes investment spending. One can debate the zero bound problem, but this article seems to imply the paradox holds when not at the zero bound. it doesn’t.

MMT rejects the modern consensus that economies should be steered primarily by the raising and lowering of interest rates. MMTers believe that the natural rate of interest in a world of fiat money is zero and that pegging it higher is a giveaway to the investor class. They say tweaking interest rates is ineffectual because businesses make investment decisions based on prospects for growth, not the cost of money

The first and final sentences are defensible, but what comes between . . . oh boy! First of all, there is no distinction made between real and nominal interest rates. I have to believe they mean real interest rates, as the alternative to is too horrible to contemplate. But why are natural real interest rates zero, and how does the central bank “peg” real interest rates?

MMT says that, contrary to appearances, banks don’t make loans out of deposits. Rather, they make loans based on the demand for borrowing, then the borrowers stash the proceeds in the bank. Anyone they write a check to simply makes a deposit in another bank. The bottom line is that loans create deposits rather than deposits creating loans.

It may not make sense to talk about deposits creating loans, but it’s equally silly to talk about loans creating deposits. As Krugman once said, “it’s a simultaneous system.”

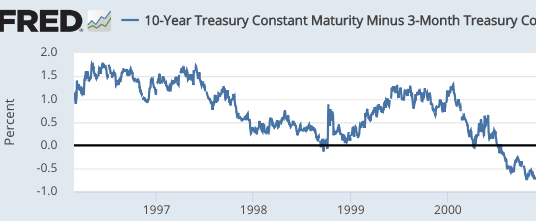

MMT challenges a core principle of conventional economics, which is that an increase in budget deficits will tend to raise interest rates, all else equal. Just the opposite, it says, sounding a bit like the White Queen from Alice in Wonderland. When the government spends more, the private sector gets the money and puts it in the banking system. With more money in the system and no increase in demand for it, interest rates will tend to fall, not rise, MMT says. That is, unless the government chooses to soak up reserves by selling bonds, which it doesn’t have to do.

So economists argue that debt financed budget deficits raise interest rates, and MMTers respond that they are wrong if you assume the deficit is not debt financed. Okaaay.

And what is the level of nominal interest rates in Latin American countries that relied on money creation to finance their deficits, not debt? I know, they didn’t follow some other provision of MMT. Stephanie Kelton once cited Japan as providing an example of how to achieve low rates with big deficits. Yes, you can hold down rates with near-zero NGDP growth over 25 years—that will “work”.

MMTers hold that inflation isn’t primarily the result of excessively strong growth. They blame much of it on businesses’ excessive pricing power. So before trying to choke off growth to kill inflation, they would try to break up monopolies and stop banks from making too many loans.

This theory was discredited by the early 1980s, and for good reason. It doesn’t explain either time series or cross sectional variation in inflation rates.

Critics of MMT reject its reassurance that a country with its own currency doesn’t need to worry about deficits. After all, it’s been proven that a nation that loses the confidence of the world’s investors will see its currency plummet. As recently as 1976, the U.K. was forced to appeal to the International Monetary Fund to stabilize the value of sterling. Wray said the U.K.’s mistake was trying to peg its currency to the dollar and the crisis eased when it allowed the pound to float.

Devaluation? What could go wrong? Have you checking the UK’s inflation rate during the 1970s?

MMT’s critics argue that trying to use fiscal policy to steer the economy is a proven failure because Congress and the president rarely act quickly enough to respond to a downturn. And they say politicians can’t be relied upon to impose pain on the public through higher taxes or lower spending to squelch rising inflation. MMTers respond that they also oppose fine-tuning and instead want to use automatic stabilizers—including the jobs guarantee—to keep the economy on track.

So we are going to achieve our 2% inflation target with “automatic stabilizers”? And what happens when President Trump decides to massively increase the budget deficit when the economy doesn’t need more spending? Who will keep inflation on target, if not the Fed?

What’s more surprising is how much flak the school of thought is taking from liberal economists who’d appear to be natural allies, such as Larry Summers, the former Treasury secretary and former Harvard president.

This might be the most puzzling comment of all. You tell all these brilliant Ivy League macroeconomists that they are fundamentally wrong in their understanding of macroeconomics, and that only a few people at places like UM Kansas City understand what’s really going on, and you are surprised that they are skeptical? Say what you will about my views; I’m not surprised that MM was not welcomed with open arms.

I sometimes have commenters discussing whether MMT “works”. That’s not even a question. Something can’t “work” unless it’s a coherent policy that can be explained and then adopted. MMT has not even reached the stage where it’s possible to discuss whether it “works”, or whether the data tends to confirm its views. For that, they need a hypothesis that impartial observers can understand.

Please don’t ever leave another comment discussing whether MMT “works”, or I might ask you to explain what it is. And I am 100% sure you will fail, because I can always find a quote from this article that proves your interpretation is wrong.

HT: Dilip