Natural experiments: Can we handle the truth?

Natural experiments are being conducted all the time. And yet I often feel like people really don’t care about the outcome of these experiments.

Let’s consider 5 popular hypotheses:

1. The mortgage interest deduction has a major impact on the housing market.

2. The NASDAQ was obviously wildly overvalued in 2000.

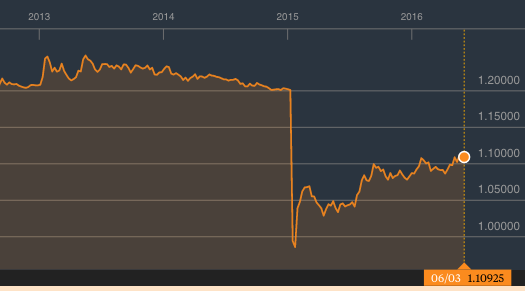

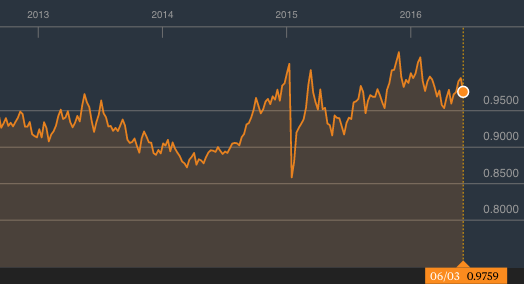

3. Switzerland was forced to revalue its currency in January 2015.

4. The US housing market was obviously wildly overvalued in 2006.

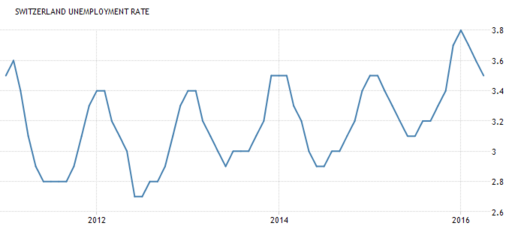

5. Brexit would cause a recession in the UK economy.

In my view, natural experiments have strongly suggested that all 5 of these hypotheses are false. And these are not trivial unimportant hypotheses, they were widely held views about some really important issues.

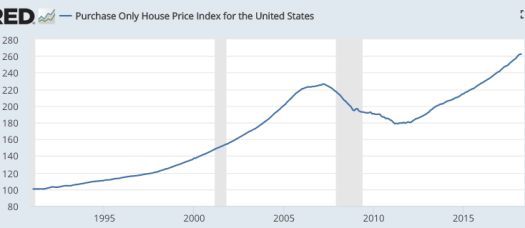

1. The tax bill that passed last year sharply cut back on the mortgage interest deduction. Before that happened I read about 1000 articles warning that if we took away this deduction it would severely hurt the housing market. We didn’t completely eliminate the deduction, but it’s more than half gone. And yet housing continues to boom. I have yet to see a single news article discussing this important natural experiment.

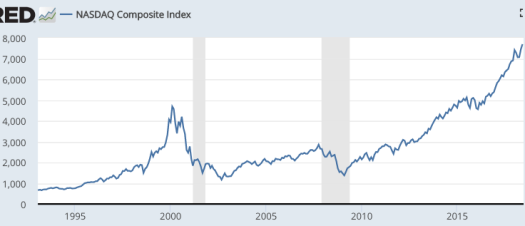

2. The Nasdaq is now far higher than in 2000. Of course it could be wildly overvalued today. Unlike in 2000, however, there is no widely held view that it is wildly overvalued today. That’s a problem for the hypothesis that it was wildly overvalued in 2000. If true, why don’t people feel that way about the current stock market? And you can’t point to changing economic circumstances, such as lower nominal interest rates, as those factors are linked to other changing economic circumstances, such as an unexpected slowdown in trend NGDP growth. I.e. where would Nasdaq be today if NGDP had grown during 2000-18 as rapidly as people expected back in 2000? Maybe 10,000?

3. Tyler Cowen correctly noted that Denmark would provide a good test of whether Switzerland was forced to revalue in January 2015. We now know that Denmark was not forced to revalue. Even worse, evidence suggests that the Swiss revaluation did not have the intended impact on the SNB balance sheet, which kept growing. That was claimed as the reason the Swiss needed to revalue. And yet despite this natural experiment, experts continue to claim that the Swiss were forced to devalue, as in this recent podcast. It seems obvious to me that the Swiss simply made a mistake—are there any good counterarguments?

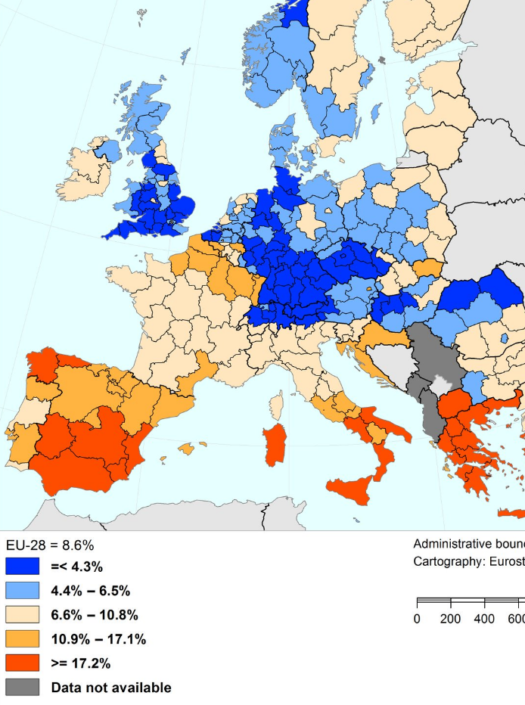

4. There are two powerful pieces of evidence against the claim that the US housing market was overvalued. First, many who made that claim also said the same thing about housing markets in Canada, Australia, the UK, and other countries. And yet many of those other countries did not crash. Even worse, America’s housing market has mostly recovered, and yet I see almost no one currently saying “America’s in a huge housing bubble, and when it crashes we’ll have another Great Recession”. So why continue to claim the 2008 recession was caused by a housing bubble that no longer even looks like a bubble at all? (And don’t point to housing construction; that’s shifting the goalposts. In 2008, everyone pointed to the historically high level of house prices in 2006; housing construction never reached unusual levels during the boom.)

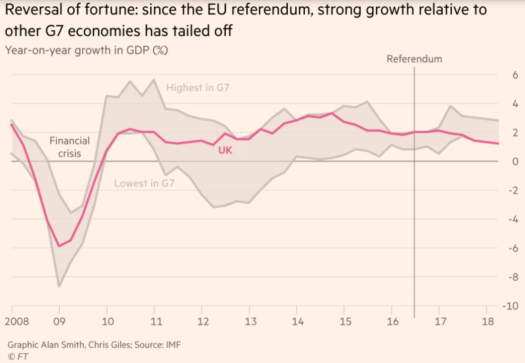

5. This one hasn’t been entirely ignored, as the Brexit supporters pointed to a strong economy after the June 2016 vote. The Financial Times claims that Brexit is now slowing British growth:

In my view it’s too soon to claim that Brexit is slowing growth. I expect it will, but the graph the FT presents does not look statistically significant to me.

Ditto on the recent corporate tax cut—it’s too soon. Both supply-siders and Keynesians expected a short term boost to growth, for different reasons. Only the supply-siders predicted a longer term boost. My own view was somewhere in between. I expect some sort of long run supply-side boost, but much less that the Larry Kudlows of the world expect. I see perhaps an extra 2% in RGDP growth spread out many years, with most of the boost coming soon after the tax cut. Supply-siders see the growth rate rising to a new trend of roughly 3%/year, which seems unlikely to me. If growth is still running at 3% in late 2019, then I clearly will have underestimated its impact. I hope I did.

I’ve done a number of previous posts on this general topic, discussing earlier experiments such as the 2013 fiscal austerity, and the 2014 elimination of extended unemployment benefits. Those who suggested that these would be good natural experiments often ignored the results when they didn’t go as expected. (GDP growth accelerated in 2013, and job growth accelerated in 2014.)

Many pundits can’t handle the truth, unless it confirms their prior beliefs.