Where are people moving? And why?

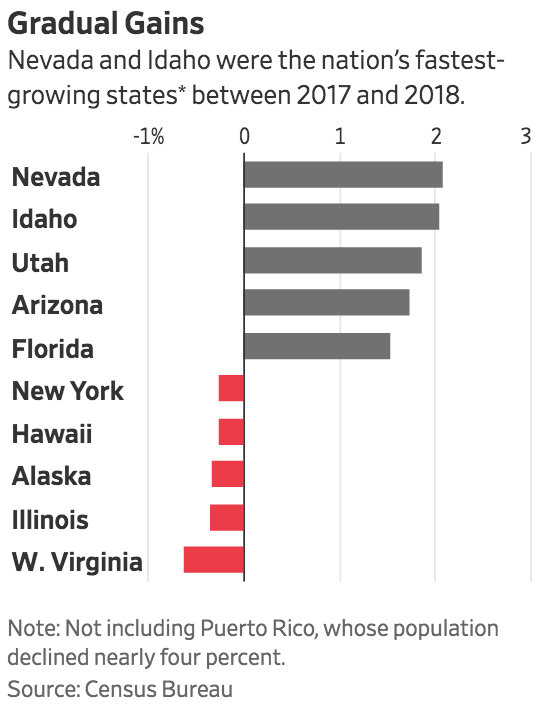

Over at Econlog, I have a post discussing the slowdown in US population growth, to 0.6% in 2018 (the slowest growth rate since 1937.) A WSJ article also had some interesting data on state growth rates:

The footnote on Puerto Rico is rather striking, as its population fell by 4% last year. That was partly due to hurricane Maria, but its population has been plunging for many years, down about 14% since 2010. Who’s going to pay off that enormous debt, and will the last Puerto Rican please turn out the lights? Hawaii is also losing people, as are Mississippi and Louisiana. So the “Sunbelt” phenomenon is more complex than advertised.

The footnote on Puerto Rico is rather striking, as its population fell by 4% last year. That was partly due to hurricane Maria, but its population has been plunging for many years, down about 14% since 2010. Who’s going to pay off that enormous debt, and will the last Puerto Rican please turn out the lights? Hawaii is also losing people, as are Mississippi and Louisiana. So the “Sunbelt” phenomenon is more complex than advertised.

Other trends:

1. Mormons have lots of kids. The four fastest growing states are all in the top five in terms of percentage of the population that is Mormon, although only in Utah and Idaho are they numerous enough to dramatically impact population growth. (The other top five Mormon state (Wyoming) is losing people.)

2. Illinois has been losing about 40,000 people each year, while other Midwestern industrial states like Michigan and Ohio keep growing (albeit slowly). What makes this surprising is that Illinois is dominated by one of the few Midwestern industrial cities to successfully reinvent itself. Chicago has a thriving lakefront area full of high paying jobs, while Detroit, Flint, Cleveland, Akron and Dayton have languished. This Illinois underperformance may reflect the extraordinary incompetence of the Illinois state government, which is driving the state toward a fiscal crisis. Illinois is dominated by Cook County, which has a corrupt political culture.

3. As recently as 2013, New York had more people than Florida. Now Florida has 1.75 million more than New York. Indeed 35% of US population growth now occurs in Florida and Texas.

4. The sunny, oil-rich states that border Texas continue to do very poorly, either falling in population or growing much more slowly than the national average. Texas probably benefits from a mixture of no state income tax, lax zoning, and business friendly regulations. While other inland states also have cheap housing prices, Texas has cheap housing prices in big urban areas.

5. It now seems like the lack of a state income tax doesn’t provide much gain to states without a big city, such as Alaska, Wyoming and New Hampshire. The exception is South Dakota, which is doing modestly better than its neighbors. In contrast, states with big cities and no state income tax (Texas, Florida, Nevada, Washington, Tennessee (on wages)) tend to grow faster than their neighbors. I think that’s because the lack of a state income tax is especially attractive for the sort of high paid professionals that live in big cities.

6. The recent federal tax reform will raise the effective top rate on the California state income tax from about 8% to 13.3%. Many rich people (like me) will continue to choose California, due to its amenities. But at the margin, a few more will make the switch to Austin or Seattle or Vegas. California always used to grow faster than the US as a whole. Even when whites started leaving for other states, the overall California population kept growing at a good clip due to international migration. But now its growth rate (0.4%) has fallen below the national average. Eventually, California may begin losing Congressional seats.

7. Today, most of our population growth is in three areas. The southeast (Raleigh to Miami), four big Texas metros, and the non-California west (the Denver/Seattle/Phoenix triangle.)

What are the odds that the world’s two richest guys would live in the same medium size city, in the only liberal state without a state income tax?