Gavyn Davies on the Fed meeting

Here’s Gavin Davies of the FT:

The startling recovery in risk assets in October – global equities rose by 11 per cent during the month – was triggered mainly by reduced pessimism on the eurozone’s debt crisis, but was probably also helped by easier monetary policy from several of the major central banks. As usual, the Federal Reserve has been in the vanguard of this action, and further measures are expected from the FOMC when it meets on Tuesday and Wednesday.

There have been calls for major innovations, such as the introduction of a target for the level of nominal GDP, but the Fed has given little indication that it is ready for anything quite so drastic. Much more likely are some further modest steps to improve the communication of the Fed’s thinking on the future path of short rates, with the aim of keeping long rates as low as possible. And there might also be some more purchases of mortgage backed securities.

This certainly caught my attention, as there were three high profile endorsements of NGDP targeting recently; Romer, Krugman and Goldman-Sachs. And there is only one person who was cited or linked to in all three statements. I’m tempted to resurrect my connecting the dots post, but can’t really do so in good faith. Davies is right; NGDP targeting is not going to be adopted at this meeting. Indeed something that important ought to be widely debated first. And that hasn’t yet occurred. Still, I’d hope to see a mention that they are at least discussing the merits.

I do think Davies might be right about monetary stimulus chatter having some effect on equity prices recently, but I don’t see any firm evidence that would make that more than a conjecture. In any case, any influence I have on that debate is an order of magnitude lower than the specific topic on NGDP targeting.

Davies continues:

Although the idea has merit, and may well be discussed by the FOMC in future, it is not likely to emerge from this week’s meetings. Ben Bernanke has discussed many radical actions for monetary policy in the past, notably relating to Japan a decade ago, but I do not recall him ever giving much attention to a nominal GDP target. He has consistently focused on the advantages of adopting a clear and consistent target for the rate of inflation (note, not the level of prices, but their rate of change, so past shortfalls would not need to be restored), and in a recent speech on 18 October he said the following:

“As a practical matter, the Federal Reserve’s policy framework has many of the elements of flexible inflation targeting…The FOMC is committed to stabilising inflation over the medium term while retaining the flexibility to help offset cyclical fluctuations in economic activity and employment.”

A couple points. Davies is right about Bernanke’s focus on inflation, but Bernanke actually has recommended the level targeting of prices. Of course it was for Japan, not the US. It’s too bad Bernanke has no interest in NGDP targeting, as it would achieve the objective laid out in that quotation far better than inflation targeting. Indeed that Bernanke quotation is a textbook argument for NGDP targets.

He went on to argue that inflation targeting had proven its worth in stabilising inflation expectations in both directions in recent years, and he concluded as follows:

“My guess is that the current framework for monetary policy – with innovations, no doubt, to further improve the ability of central banks to communicate with the public – will remain the standard approach, as its benefits in terms of macroeconomic stabilisation have been demonstrated.”

If a 9% fall in NGDP below trend from mid-2008 to mid-2009, which led to massive and costly fiscal stimulus in the desperate hope it would prop up the very same aggregate demand that the Fed is supposed to be controlling is “benefits . . . demonstrated,” I’d hate to see a failed monetary policy. And then there’s the sub-5% NGDP growth during the 27 month “recovery.”

Janet Yellen is particularly important here, since she is in charge of a Fed committee examining the matter. In her speech, she said:

“We have been discussing potential approaches for providing more information “” perhaps through the SEP “” regarding our longer-run objectives, the factors that influence our policy decisions, and our views on the likely evolution of monetary policy.”

The SEP is the Summary of Economic Projections, in which FOMC members give their outlooks for the main economic variables in the years ahead. It seems from Janet Yellen’s guidance that the Fed might decide to beef up this document so that it becomes more explicit about the nature of its long run inflation and unemployment objectives, and about the conditions underpinning its commitment to hold interest rates close to zero until mid 2013.

It is even possible that FOMC members might start to publish their entire expected path for short rates over future years, conditional on their economic forecasts. (Read my lips: no new rate hikes!”) The Chairman has explicitly pointed out that other central banks publish such projections of policy rates, which help influence market expectations of central bank policy.

The idea here would be to increase the confidence of the markets that short rates are intended to remain at zero for a very long time to come, which might in turn reduce long bond yields even further. That would be useful in easing monetary policy slightly, but it cannot be expected to have very much effect when short rate expectations are already so low. More drastic options, like a target for the level of nominal GDP, will have to wait a while.

That doesn’t do much for me. I’d say lower long term rates are more likely to be “evidence that monetary policy remains ineffective,” rather than “useful in easing monetary policy slightly.” The Fed is still a long way from the point where it comes to grips with what actually needs to be done. But at least they are searching for answers.

HT: Richard W.

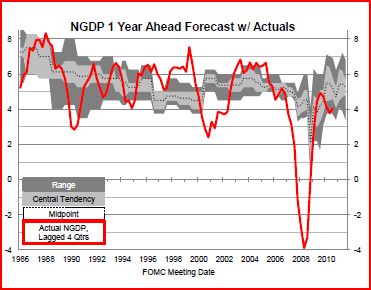

PS. Joshua Lehner just sent me some interesting graphs comparing actual NGDP growth with Fed forecasts at different time horizons. They obviously envision roughly 5% NGDP growth, and just as obviously aren’t doing level targeting. Interestingly, he said the Fed stopped doing explicit NGDP forecasts in 2005, now it’s just RGDP and P. That’s a bad sign.

Update: Josh Lehner send me this post from his blog.