The hawkish case

The future course of the economy always involves a bit of guesswork. But it seems to me that the following two claims are pretty likely to be true:

1. Over the past three years, monetary policy has been far too expansionary.

2. It is likely that monetary policy is still a bit too expansionary, although I have less confidence in that claim.

Here are some recent data points, starting with the Financial Times:

A “blowout” March retail sales report sparked a sell-off in US government debt and shook global currency markets on Monday, in the latest sign that the world’s largest economy may be running too hot to justify cutting interest rates.

US retail sales were much stronger than expected in March, as consumers kept spending despite uncertainty about the future path of interest rates. [Note the term “despite”]

Data from the US Census Bureau published on Monday showed that retail sales, which include spending on food and petrol, rose 0.7 per cent last month. Economists surveyed by Reuters had expected an increase of 0.3 per cent.

The figure for February was revised up from a rise of 0.6 per cent to one of 0.9 per cent, indicating resilient consumer spending earlier this year and providing further evidence of a reacceleration of economic growth.

That should read: Reacceleration of nominal economic growth.

Five-year TIPS spreads are back over 2.5%, and rising.

The Atlanta Fed nowcast for real GDP growth is up to 2.8%, implying continued strong nominal growth in Q1. You cannot control inflation without controlling nominal GDP.

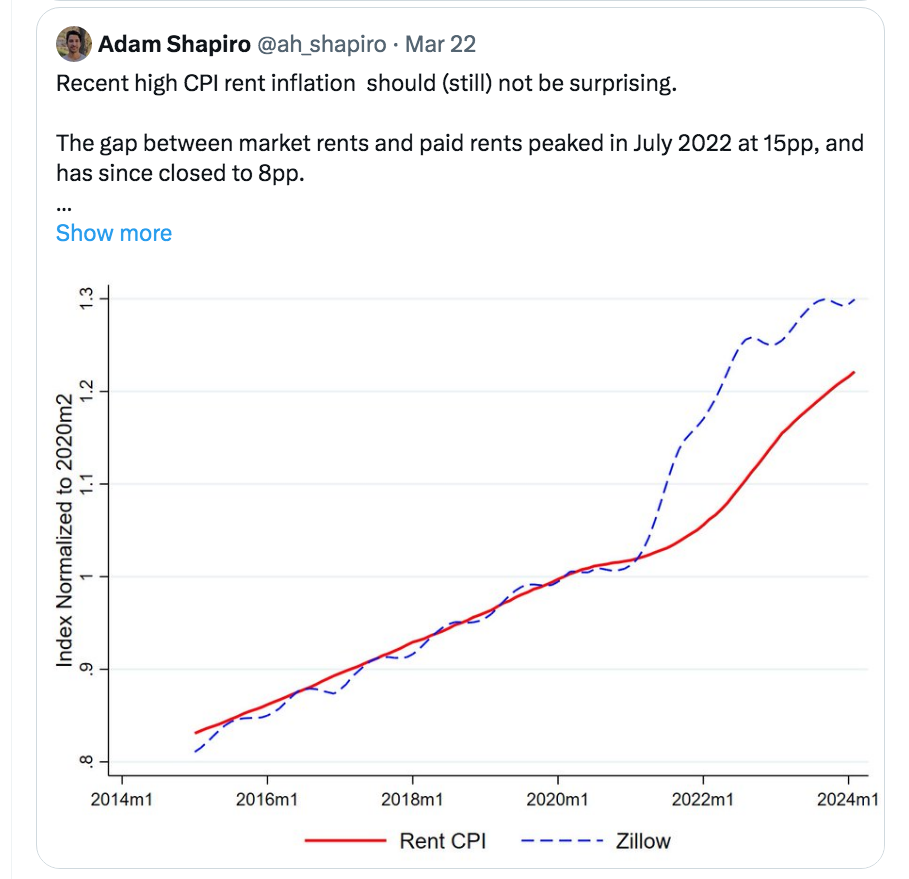

Some people argue that the slowdown in “spot rents” will soon show up in CPI rents. Maybe so, maybe not. It depends on the future course of spot rents, as CPI rents still have a long way to go to catch up with previous increases in spot rents:

If spot rents now begin re-accelerating, then we’ll never get that promised slowdown in CPI rents. Multifamily housing construction is slumping, a bad sign.

I’m not suggesting that inflation cannot slow in the months ahead, as it is impossible to foresee turning points in the economy. Perhaps we’ll be in recession in late 2024. But I do believe the weight of evidence points toward an increased risk of inflation. Given that policy over the previous three years has obviously been way too expansionary, the Fed needs to err on the side of hawkishness (even at the risk of recession.) If you wonder “what’s so bad about 3% inflation”, then you haven’t understood a single thing I’ve said here over the past 15 years.

This is the point where economists discuss “what the Fed should do”, by which they mean where should they set the fed funds target. In my view, interest rates are not the right way to think about monetary policy, so I won’t recommend a particular rate setting. Instead, I’ll recommend making the policy regime more effective.

1. Stop being so clumsy. Right now, the Fed has a psychological aversion to unexpected changes in interest rates. Thus they’d rather not raise rates. But that psychological aversion is irrational, and it makes policy less effective. (I.e., it makes both a recession and an inflation overshoot more likely.) The Fed should adjust their fed funds target daily, to the closest basis point (say using the median vote of FOMC members.) The Fed funds target should look like other market prices, like a random walk. New information should not make people expect a different level of NGDP in 2025, rather new information should show up as the adjustment in the fed funds rate required to keep expected 2025 NGDP on target.

2. Switch to level targeting. The failures of the past three years have many causes, but one factor is of overriding importance. The Fed thinks in terms of growth rates, not levels. That radically increases uncertainty about the future path of NGDP, and largely explains the wild swings in the financial markets in response to seemingly trivial adjustments in Fed policy.

The Fed is not reacting to unexpected swings in aggregate demand, the Fed is creating unexpected swings in aggregate demand, through its clumsy interest rate targeting system and lack of level targeting.

Tags:

16. April 2024 at 08:21

“The Fed funds target should look like other market prices, like a random walk. New information should not make people expect a different level of NGDP in 2025, rather new information should show up as the adjustment in the fed funds rate required to keep expected 2025 NGDP on target.”

I think you could make an argument that if the Fed is doing its job, then the futures price on 2025 NGDP would be a random walk (or more specifically log 2025 price adjusted for the 2025 NGDP target). I’m not sure that implies that the Fed funds target would also be one. Maybe approximately random walk. Or maybe that daily differences in the Fed Funds target should be approximately white noise.

Two potential reasons for this:

1) Level targeting of NGDP would mean that the target for the year ahead depends on prior performance of NGDP. The instrument needed to implement that policy (interest rates) should also depend on prior year behavior.

2) Interest rates in general are at best approximately random walks. They have long-run mean-reverting behavior that isn’t present in stocks and behave differently when nominal yields get close to zero.

16. April 2024 at 10:22

A few rounds of Hawkish forward guidance and they could do the rate cut everyone was expecting. Pull is down from 6% year-ahead NGDP growth to 4.5%.

16. April 2024 at 12:14

John, You said:

“futures price on 2025 NGDP would be a random walk”

I don’t follow. The futures price should be stable.

Justin, Yes, that’s possible.

16. April 2024 at 14:25

Why don’t you tell George Selgin that money creation is a system’s process, not an individual bank’s process.

The flagrant degree of the looseness in the current monetary policy is criminal.

16. April 2024 at 16:05

resuggestion 1. My version of this idea is that the fed need to drop this 3rd hidden mandate they have adopted to “normalize” interest rates. We saw this on the opposite end, where once the fed decided they no longer needed to cut, the next move was assumed to be a hike in order to “normalize” because interest rates are *supposed* to be about 4% and therefore absent the obvious need to do anything specific, they need to work their way back to 4. In 2009 the result of this was that monetary policy was tighter than they intended and now the result is that its looser.

Indeed a radical change in procedure may be the best way to break this psychology. But the exact procedure is probably less important than the psychology breaking. Of course they also need to believe that 3rd mandate is wrong to want to break the psychology. I am not convinced they believe it.

16. April 2024 at 16:13

Scott, in your guardrails approach it need not be stable. It could vary up and down within a range. It might actually have some mean-reverting properties actually now that I think on it.

Another consideration is whether you are thinking about a specific year’s NGDP forecast as opposed to a fixed one-year ahead forecast. If the Fed aims to stabilize a hypothetical one-year ahead NGDP forecast (without guardrails), then that might be constant, but as the specific year’s forecast wouldn’t, especially as you get closer to the contract expiration.

16. April 2024 at 16:20

Sure target NGDP.

I still don’t see what is so bad about 3% inflation.

The Reserve Bank of Australia targets a band of 2% to 3%.

The Reserve Bank of India targets a 4% rate of inflation inside a

4% band.

Maybe 1000 times more important is how to build several million more units of housing in the United States, perhaps even ten million more units.

16. April 2024 at 18:34

It finally happened. I’m more hawkish than Scott. After all of these years,…

I’m more certain monetary policy has loosened over the past couple of quarters, and it continues to loosen, as evidenced by the rising inflation breakevens pointed to in this post. Also, my estimate of the NGDP output gap is a positive 1.8% over the past two quarters. That’s an increase over Q3, when it was 1.4%.

When the economy is supposed to slow as part of an effort to reduce inflation, and the stock market is in a bull run, that’s a pretty good bet something is wrong. Even if real shocks drive stock prices higher, the Fed shouldn’t be allowing NGDP growth expectations to rise. And then to note inflation expectations rising too, with recent inflation and jobs reports topping expectations?

The real question is, what’s the evidence to counter that monetary policy has been getting looser?

16. April 2024 at 20:12

Andrew, It’s not just about normalizing rates, they also don’t like doing “embarrassing” U-turns. But there’s nothing embarrassing about a U-turn, it’s how optimal policies are supposed to work.

John, Yes, although as you know I favor level targeting.

Michael: “what’s the evidence to counter that monetary policy has been getting looser?”

Good question.

17. April 2024 at 03:50

Contrary to the FED’s technical staff, retail MMMFs are nonbanks.

In my 1958 Money and Banking text. “Purchases and sales between the Reserve banks and non-bank investors directly affect both bank reserves (outside money) and the money stock (inside money).”

Mises has it right:

“The definition of M2 includes money market securities, mutual funds, and other time deposits. However, an investment in a mutual fund is in fact an investment in various money market instruments. The quantity of money is not altered as a result of this investment; the ownership of money has only changed temporarily. Hence, including mutual funds as part of M2 results in the double counting of money.”

see: “Correlations and the Definition of the Money Supply”

October 19, 2023

https://www.misesfans.org/2023/10/correlations-and-definition-of-money.html

There’s not much new under the sun. It’s the credit school vs. the money school.

Since the monetary authorities make their determinations on the basis of the size and not the “mix” or the bank credit proxy, there is no a priori reason to assume that an expansion of time deposits will alter the FOMC’s consensus as to the proper volume and rate of change in bank credit.

The FOMC’s proviso “bank credit proxy” used to be included in the FOMC’s directive during the period Sept 66 – Sept 69. That’s the “credit school” (that the money stock is a by-product of credit policy, as opposed to the “money school” (the tangible stock of our primary or means-of-payment money supply, is the only valid indicator of monetary conditions).

Increases in DFI loans and investments [earning assets/bank credit], are approximately the same as increases in transaction accounts, TRs, and time deposits, TDs, [savings-investment deposits/bank liabilities/bank credit proxy] excluding IBDDs.

That the net absolute increase in these two figures is so nearly identical is no happenstance, for TRs largely come into being through the credit creating process, and TDs owe their origin almost exclusively to TRs – either directly through transfer from TRs or indirectly via the currency route or through the DFI’s undivided profits accounts.

In the credit school, large CDs constitute an increase in credit. They are thus, obviously, an increase in the money stock. Large CDs represent shifts from other deposit classifications. In other words, monetary policy is loose. Combine that with the FED counting MMMFs as banks and you get the rise in gold and other commodities, in other words, a rise in inflation.

17. April 2024 at 04:05

The level targeting is why I mentioned before about how you need to make a transformation to get something more like a random walk. If you take the one-year ahead nominal GDP growth forecast (in gross terms, so 1 + g) and divide by the current nominal GDP growth target, then that should be more stable over time. The growth target will shift up and down depending on what is required for the level targeting. I just mean that you can express the level target in terms of a varying growth target. The actual implementation, that is.

17. April 2024 at 04:25

If, for example, large CDs were expanding as fast as the banks were making loans and creating new demand deposits, the money supply would remain virtually stationary. The money supply criterion would therefore create the illusion that a tight money policy was in effect.

18. April 2024 at 05:26

I agree with your general point, but…

‘The Fed funds target should look like other market prices, like a random walk.’

Market prices don’t look like a random walk!

18. April 2024 at 09:25

BTW, SPF NGDP one-year ahead forecast was 4% in Q1.

18. April 2024 at 11:53

“Market prices don’t look like a random walk!”

They do to me!

18. April 2024 at 17:34

There was a theory that says that changes in monetary policy are only effective when they are unexpected. But, the modern Fed is deeply afraid of scaring the market and only moves rates when the path has been sufficiently telegraphed.

This moves the Fed watchers to look for unexpected changes in the Fed’s signals. And so, is it the case that changing signals is the Fed’s effective action?

19. April 2024 at 08:29

Looking at the one-year rate of change in total reserves you see why stocks and commodities have recently risen. But that is only available since February. I.e., the FED eschews monetarism.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTRESNS

The only tool, credit control device, at the disposal of the monetary authority in a free capitalistic system through which the volume of money can be properly controlled is legal reserves. Powell eliminated legal reserves in March 2020. And Powell also eliminated deposit classifications.

Dr. Daniel L. Thornton, May 12, 2022:

“However, on March 26, 2020, the Board of Governors reduced the reserve requirement on checkable deposits to zero. This action ended the Fed’s ability to control M1.”

19. April 2024 at 08:37

Because the distributed lag effect of monetary flows, the proxy for inflation, is 24 months, the FED can tighten N-gDp after two consecutive quarters of greater than 5% growth rates?

19. April 2024 at 08:37

Because the distributed lag effect of monetary flows, the proxy for inflation, is 24 months, the FED can tighten N-gDp after two consecutive quarters of greater than 5% growth rates?

20. April 2024 at 10:29

Doug, Of course signals are all important, but only because they are signals about concrete actions that will occur in the future.

21. April 2024 at 17:10

I haven’t heard you say much explicitly about who, in your preferred system, is supposed to assume the risk of things not evolving according to plan. Most of your advice here is oriented towards the Fed not making obvious, horrendously bad unforced errors (eg., telegraphing your trades, waiting months to act) that would get any private money manager instantly fired. But it seems like in the past 15 years an attitude has evolved that the government is supposed to deliberately act suboptimally in order to assume more risk from private investors and also to routinely “leave a little money on the table” so private players can pick it up. I don’t know where exactly this came from, or if it is just a vague sense that a clumsy Fed somehow promotes political and economic stability, but I would tend to think that it does in fact run counter to the goal of promoting long term stability of the system.

22. April 2024 at 07:07

The colossal error in macroeconomics is that banks lend deposits. But when a bank makes loans to, or buys securities from, the nonbank public, it creates a dollar-for-dollar expansion of bank deposits.

That in and of itself, is the basis for saying banks don’t lend deposits. Otherwise, in financial intermediation, the money stock would remain unchanged.

I.e., other things equal, lending by the DFIs is inflationary, whereas lending by the NBFIs is noninflationary.

The US Golden Age in Capitalism was where small savings were pooled, expeditiously activated, and put back to work. I.e., the intermediaries, the nonbanks (backstopped by the FSLIC, NCUA etc._, grew much faster than the banks (making the bankers jealous, driving up Reg. Q ceilings).

Economist John O’Donnell said of the U.S. Golden Era in Economics: “increased money velocity financed about two-thirds of a growing GNP, while the increase in the actual quantity of money has financed only one-third.

Any economist that argues otherwise, doesn’t understand money and central banking period. So, Powell doesn’t understand money and central banking.

22. April 2024 at 07:47

“If you wonder “what’s so bad about 3% inflation”, then you haven’t understood a single thing I’ve said here over the past 15 years.”

How does this sentence align with your goals?

22. April 2024 at 10:40

Scott, People have asked me this question approximately 1342 times over the past 15 years. It aligns with my goal to not have the question asked a 1343rd time.

22. April 2024 at 21:55

Scott H.,

Inflation rates don’t matter much, as long as they’re anchored and mild. You don’t want high inflation due to the effects on capital and other distortions, and you don’t want too much deflation, because wages are sticky and it can lead to unnecessary unemployment. A zero inflation rate is superior to positive inflation, in my view, and mild deflation is even better. Hence, raising the inflation target to 3% would make us slighly worse off.

Also, it’s a bad time to switch to a higher inflation target while the Fed is trying to gain credibility on getting back to 2%. For one thing, this would represent a positive nominal shock that would initially push real growth above sustainable capacity, leading to a sharp growth downturn or even a recession when wages caught up. Then, the Fed also risks losing credibility, putting the inflation anchor at further risk.

Even more fundamentally though, Scott has argued that inflation is an artificial construct, as is real GDP growth by extension. NGDP growth represents the variable that really matters on the demand side, which is aggregate demand. On the supply side, it’s all about sticky wages. In a large, diversified economy like the US, NGDP targeting should be nearly as good as targeting nominal wage growth, and would be much easier to execute given the market indicators available.

NGDP targeting is better, because it isn’t pro-cyclical, like inflation targeting. An NGDP target keeps aggregate demand on a stable growth path, while allowing inflation due to supply shocks to fluctuate. This avoids situations like the Fed-fueled “bubble” of the late 90s and early 00s, and the Great Recession. Inflation fell in the former case as productivity growth soared, with the Fed boosting NGDP growth above trend until inflation approached 3%. Then the Fed pumped the brakes a bit too hard. The opposite problem occurred during the Great Recession. Commodity prices were spiking, and the Fed tightened policy, failing to see through these temporary price shocks, causing the Great Recession.

22. April 2024 at 22:05

I should add though that a symmetric flexible average inflation target is similar enough to NGDP targeting, that the Fed could target NGDP under such a framework and it would hardly be noticeable. There’ve even been periods during the Great Moderation and the period of the the Great Recession recovery in which the Fed pretty closely approximated NGDP targeting, but with too much volatility.

23. April 2024 at 05:54

“Republican fans of Putin don’t seem to understand that he also opposes liberal values such as pluralism, freedom of speech and assembly, and free elections.”

Ukraine doesn’t have any of those either, which is part of the reason why it is so heavily supported by neo-Nazis and White Nationalists. Of course, that does not in itself justify the Z war. And did pre-2022 Russia have less freedom of speech than France or Britain? I don’t think so.

“neither major party nominated Charles Lindbergh to run for president.”

Trump isn’t Lindbergh; he was the one who first approved of weapons sales to Ukraine back in 2017. Had he an actually dovish policy towards Russia, I don’t think the Z war would have happened.

“In a town hall last year, Trump refused to say whether he wanted Ukraine or Russia to win the war.”

Come on; Sumner, you know this is nonsense. Trump has clearly called the Z war a genocide.

23. April 2024 at 08:57

Harding, So the fact that Trump often says pro-Putin things and sometimes says anti-Putin things is evidence AGAINST my claim that his views on Putin are “ambivalent”? Okay . . .

“And did pre-2022 Russia have less freedom of speech than France or Britain? I don’t think so.”

LOL

25. April 2024 at 18:02

The yield curve inversion first appeared in Jul22, and I’ve heard recession lags 12-30 months – the top end of that range is still in front of us. With today’s surprisingly weak GDP number, have you become more dovish, or does one datapoint lack credibility in your view, or something else?

Also if AI boosts output like everyone thinks, it will come in the form of increased efficiency and lower costs – a deflationary boost in supply. Might this add to the doves’ case?

Lastly how do you see the yield curve uninverting? Without the return of QE and with continued fiscal irresponsibility, would you agree higher long terms seem likely even if we have a recession?

25. April 2024 at 20:06

Thomas, GDP growth was 4.7% in Q1, that’s still too strong. (RGDP doesn’t matter.)

AI might affect productivity at some point, but we are still at least a few years away.

A recession would certainly reduce rates, but I agree that big deficits probably are having some impact on the long-term interest rate. The biggest recent factor, however, is excessive NGDP growth, which drives nominal interest rates higher.