Do low interest rates stimulate housing?

If you answer this question with a “yes”, then you are reasoning from a price change. I thought of this when reading the abstract to a paper by David W. Berger, Konstantin Milbradt, Fabrice Tourre, Joseph Vavra on monetary policy and mortgage interest:

How much ability does the Fed have to stimulate the economy by cutting interest rates? We argue that the presence of substantial household debt in fixed-rate prepayable mortgages means that this question cannot be answered by looking only at how far current rates are from zero. Using a household model of mortgage prepayment with endogenous mortgage pricing, wealth distributions and consumption matched to detailed loan-level evidence on the relationship between prepayment and rate incentives, we argue that the ability to stimulate the economy by cutting rates depends not just on the level of current interest rates but also on their previous path: 1) Holding current rates constant, monetary policy is less effective if previous rates were low. 2) Monetary policy “reloads” stimulative power slowly after raising rates. 3) The strength of monetary policy via the mortgage prepayment channel has been amplified by the 30-year secular decline in mortgage rates. All three conclusions imply that even if the Fed raises rates substantially before the next recession arrives, it will likely have less ammunition available for stimulus than in recent recessions.

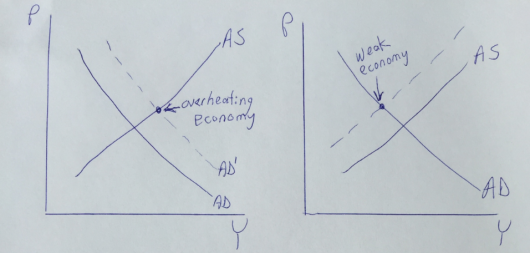

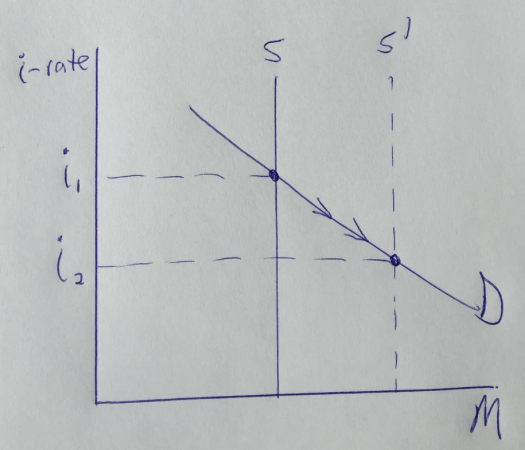

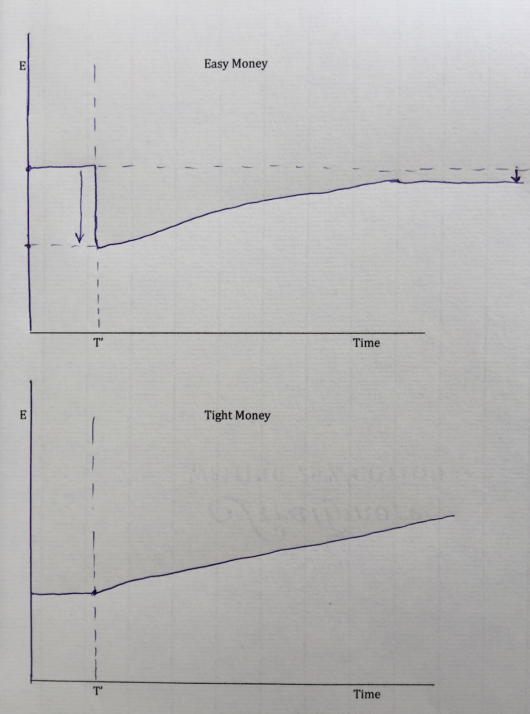

People tend to refinance mortgages when long-term interest rates fall. So what type of monetary policy generally causes long-term interest rates to decline? I’d say the answer is contractionary, whereas the authors of this study seem to assume the answer is expansionary. (I base this assumption on the first sentence of the abstract. I have not read the entire paper, so it’s very possible I misinterpreted their claim.)

This is actually a complex question, and my reading of the evidence is that long-term rates will usually increase when monetary policy is made more expansionary (as in the 1960s and 1970s), but not always. Of course it partly depends on how you define “expansionary”.

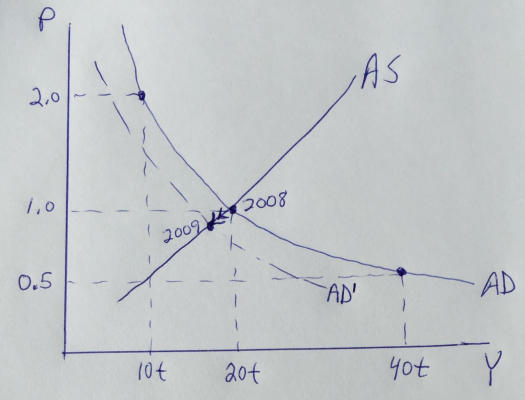

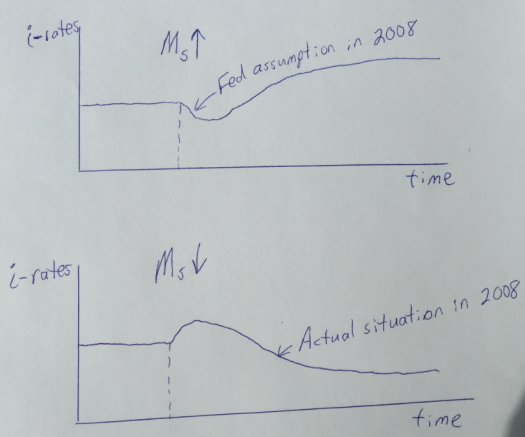

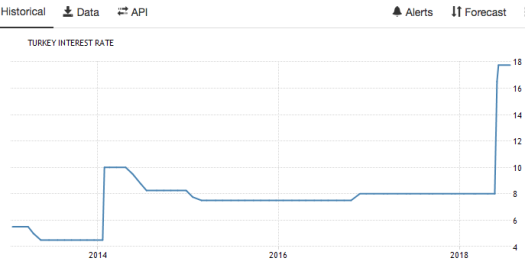

Consider the Fed announcements of January 2001 and September 2007. In both cases, the Fed cut rates for the first time in years. In both cases, the policy rate was cut by 0.5%, not the usual 0.25%. In both cases, stocks soared on the unexpectedly expansionary policy news. In both cases, long-term bond yields increased on the news (dramatically in January 2001), even as short term rates declined. If a highly liquid NGDP futures market had existed, then NGDP futures prices would have probably also increased. On the other hand, you can also find lots of examples where short and long-term interest rates move in the same direction. But the two cases I cited are important because they were so easily identifiable–the dramatic market responses at 2:15 pm seemed clearly linked to the Fed announcements. “Identification” of policy shocks is easier in that case.

If I’m right that falling long-term bond yields generally reflect a contractionary monetary policy, then I think it’s a mistake to rely too much on the mortgage refinance channel when the Fed is trying to stimulate the economy.

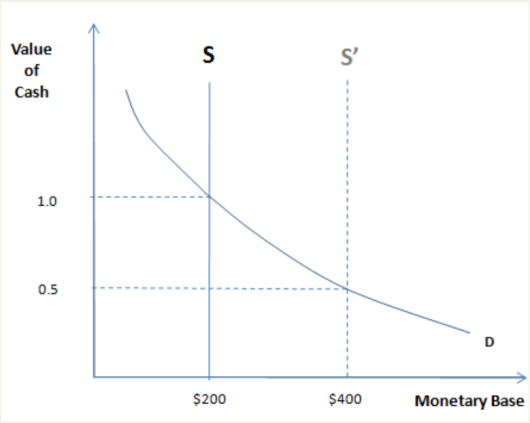

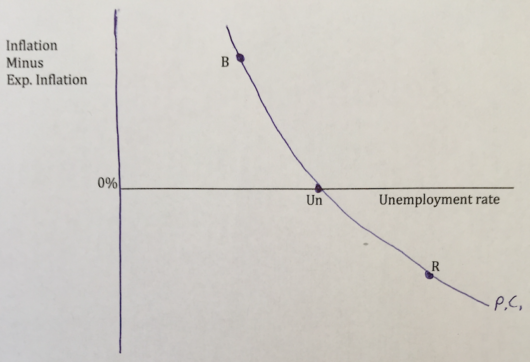

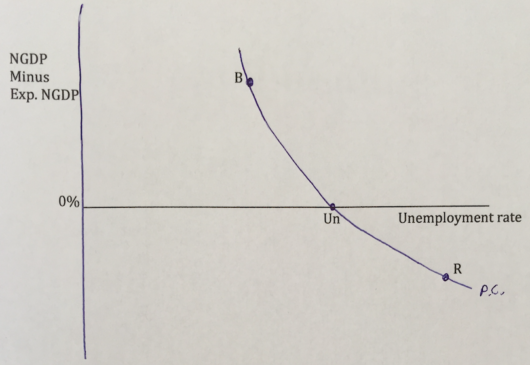

I believe that monetary policy is always highly effective, even at zero interest rates. We have lots of historical evidence to support that claim. But if it is effective, it’s not because lower interest rates stimulate demand, rather it is because monetary stimulus increases the monetary base and/or reduces base demand, which boosts NGDP. And higher NGDP leads to higher employment in a world with sticky wages. In most cases, long term interest rates will also increase.

HT: Tyler Cowen