Here’s something that caught my eye:

Federal Reserve officials are increasingly making the case that Congress should spend more money to stimulate the economy, with an eye on the infrastructure package that could hit the agenda next year.

Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen and Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer have both nudged Congress in recent speeches. They said federal spending that bolsters demand and increases the labor force would take pressure off of monetary policy and help grow the economy.

“There are ways in which the response of fiscal policy to shifts in the economy could be strengthened, which could help take some burden off of monetary policy,” said Yellen in a September press conference.

“Fiscal policy has traditionally played an important role in dealing with severe economic downturns,” said Yellen in an August speech, suggesting work on “improving our educational system and investing more in worker training; promoting capital investment and research spending, both private and public; and looking for ways to reduce regulatory burdens while protecting important economic, financial, and social goals.” (emphasis added)

I don’t use the term ‘bizarre’ lightly, as this stuff is not just wrong, or doubly wrong, it’s quintuply wrong. It’s not even slightly defensible:

1. The Fed claims the economy does not need any more demand stimulus. Indeed any boost to AD from more spending would be offset by tighter money. So what’s the point?

2. Even if fiscal stimulus were needed, it should be done via tax cuts. It’s not efficient to vary spending for anything other than standard cost/benefit reasons, where benefits do not include demand stimulus. And why should the central bank be telling Congress where to spend money?

3. The Fed might respond that fiscal stimulus would not boost demand, but it would allow the current demand to be achieved with less monetary stimulus. But why is that desirable?

4. The Fed might argue that it would prefer a higher trend rate of nominal interest rates, so that it hit the zero bound less often in future recessions. But fiscal stimulus is an absolutely HORRIBLE way to achieve that objective:

a. Fiscal stimulus can only boost nominal interest rates by raising the global real rate of interest. Just imagine how much fiscal stimulus it would take to boost the global real rate of interest by even 100 basis points. (Hint: far, far beyond anything Congress would ever contemplate.) Then think about how Japan did a massive amount of fiscal stimulus in the 1990s and 2000s, and ended up with some of the lowest interest rates the world has ever seen.

b. In contrast, monetary stimulus can easily raise nominal interest rates by 100 basis points, merely by raising the inflation target from 2% to 3%. So why would the Fed prefer fiscal stimulus as a way of raising nominal rates? Is the Fed seriously arguing that the sort of fiscal stimulus needed to boost global real interest rates by one percent is more efficient than simply raising the inflation target by 1%? And if so, why is it that when inflation targeting was first being discussed and implemented in the 1990s, all of the academic discussion focused on the importance of setting the inflation target high enough to avoid the zero bound problem, and approximately zero effort was devoted to the idea that fiscal stimulus could raise the long term trend real interest rate, if the zero bound were a problem. Were the economists of the 1990s stupid?

5. Economists agree, or used to agree that the US and other developed countries face severe long-term fiscal changes, due to an aging population. The consensus is, or used to be, that now is a good time to start addressing these issues. (Remember Simpson/Bowles?) It would be one thing if the Fed were proposing a short-term fiscal stimulus to boost demand right now. But they aren’t, they don’t think we need more demand right now. Instead they are proposing a long-term fiscal stimulus, which would massively worsen the already worrisome long-term fiscal trends in America. A decade ago, sensible economists (like Krugman) criticized these sorts of proposals as reckless, and they were right. Japan has already shown that decades of fiscal stimulus do nothing to raise NGDP growth, and merely leave you with a higher debt/GDP ratio. Why would we want to copy Japan’s failed experiment? All they ended up with is lots of highway projects that are little used, and destroyed some of the once beautiful Japanese countryside.

6. What does improving education have to do with fiscal stimulus? The US already spends more on public education than most countries, and education experts seem to agree that the real problem is poorly designed schools or bad home environment, not lack of money. Would throwing a few more billions of dollars at the LA school system boost growth? Would it turn the LA system into the Palo Alto system? How?

The passage I quoted is modern progressivism at its worst. A lot of nice sounding bland generalities, that mean nothing. I mean seriously, “working training”? What a brilliant idea!! Amazing that humanity never thought of that before, in 5000 years of human history. While we are at it, let’s reduce federal spending by 10% solely by cutting “waste, fraud and abuse”, without touching any “needed programs”.

And if the Fed is so worried about unemployment, how about telling the government not to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour? Let me guess, that would not sound progressive.

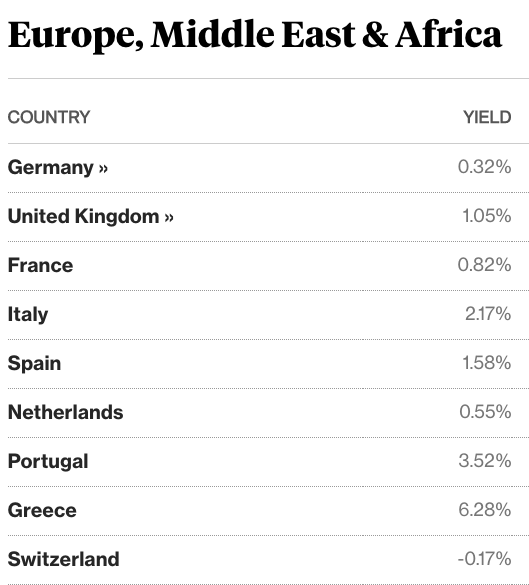

As you can see, Italian 10-year bonds offer considerably higher yields than German, French and Dutch bonds, and even higher yields than Spanish bonds. Italy has a massive public debt (third largest in the world), an economy that has shown almost no growth since 2000, and a very dysfunctional political system (which the voters recently decided not to reform.)

As you can see, Italian 10-year bonds offer considerably higher yields than German, French and Dutch bonds, and even higher yields than Spanish bonds. Italy has a massive public debt (third largest in the world), an economy that has shown almost no growth since 2000, and a very dysfunctional political system (which the voters recently decided not to reform.)