Over at Econlog I did a post discussing the austerity of 1946. The Federal deficit swung from over 20% of GDP during fiscal 1945 (mid-1944 to mid-1945) to an outright surplus in fiscal 1947. Policy doesn’t get much more austere than that! Even worse, the austerity was a reduction in government output, which Keynesians view as the most potent part of the fiscal mix. I pointed out that employment did fine, with the unemployment rate fluctuating between 3% and 5% during 1946, 1947 and 1948, even as Keynesian economists had predicted a rise in unemployment to 25% or even 35%—i.e. worse than the low point of the Great Depression. That’s a pretty big miss in your forecast, and made me wonder about the validity of the model they used.

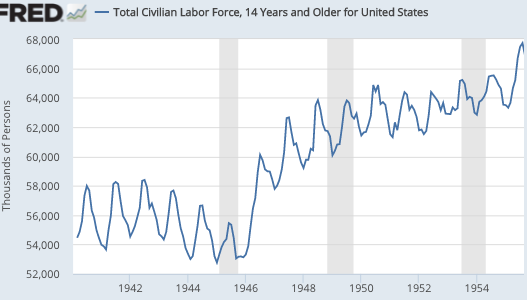

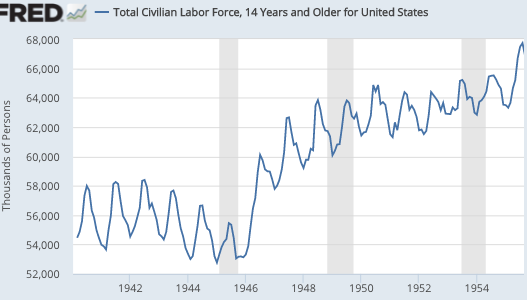

One commenter pointed out that RGDP fell by over 12% between 1945 and 1946, and that lots of women left the labor force after WWII. So does a shrinking labor force explain the disconnect between unemployment and GDP? As far as I can tell it does not, which surprised even me. But the data is patchy, so please offer suggestions as to how I could do better.

Let’s start with hours worked per week, the data that is most supportive of the Keynesian view:

Weekly hours worked dropped about 5% between 1945 and 1946. Does that help explain the huge drop in GDP? Not as much as you’d think. Here’s the civilian labor force:

So the labor force grew by close to 9%, indicating that the labor force in terms of numbers of worker hours probably grew. Indeed if you add in the 3% jump in the unemployment rate, it appears as if the total number of hours worked was little changed between 1945 and 1946 (9% – 5% – 3%). Which is really weird given that RGDP fell by 22% from the 1945Q1 peak to the 1947Q1 trough–a decline closer to the 36% decline during the Great Contraction, than the 3% fall during the Great Recession.

That’s all accounting, which is interesting, but it doesn’t really tell us what caused the employment miracle. I’d like to point to NGDP, which did grow very rapidly between 1946 and 1948, but even that doesn’t quite help, as it fell by about 10% between early 1945 and early 1946.

Here’s why I think that the NGDP (musical chairs) model did not work this time. Let’s go back to the hours worked, and think about why they were roughly unchanged. You had two big factors pushing hard, but in opposite directions. Hours worked were pushed up by 10 million soldiers suddenly entering the workforce. In the offsetting direction were three factors. A smaller number of (mostly women) workers leaving the workforce, unemployment rising from 1% to 4%, and average weekly hours falling by about 5%. All that netted out to roughly zero change in hours worked.

So why did RGDP fall so sharply? Keep in mind that while those soldiers were fighting WWII, their pay was a part of GDP. They helped make the “G” part of GDP rise to extraordinary levels in the early 1940s. But when the war ended, that military pay stopped. Many then got jobs in the civilian economy. Now they were counted as part of hours worked. (Soldiers aren’t counted as workers.) That artificially depressed productivity.

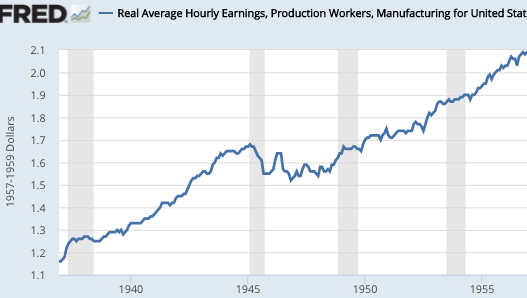

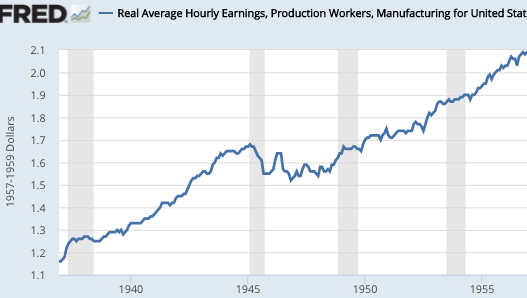

It’s also worth noting that real hourly wages fell by nearly 10% between February 1945 and November 1946:

This data only applies to manufacturing workers. But keep in mind that the 1940s was the peak period of unionism, so I’d guess service workers did even worse. So my theory is that the sudden drop in NGDP in 1946 was an artifact of the end of massive military spending, and the strong growth in NGDP during 1946-48, which reflected high inflation, helped to stabilize the labor market. When the inflation ended in 1949, real wages rose and we had a brief recession. By 1950, the economy was recovering, even before the Korean War broke out in late June.

Obviously 1946 was an unusual year, and it’s hard to draw any policy lessons. At Econlog, I pointed out that the high inflation occurred without any “concrete steppes” by the Fed; T-bill yields stayed at 0.38% during 1945-47 and the monetary base was pretty flat. Some of the inflation represented the removal of price controls, but I suspect some of it was purely (demand-side) monetary—a rise in velocity as fears of a post-war recession faded.

This era shows that you can have a lot of “reallocation” and a lot of austerity, without necessarily seeing a big rise in unemployment. And if you are going to make excuses for the Keynesian model, you also have to recognize that most Keynesians got it spectacularly wrong at the time. Keynesians often make of big deal of Milton Friedman’s false prediction that inflation would rise sharply after 1982, but tend to ignore another monetarist (William Barnett, pp. 22-23) who correctly forecast that it would not rise. OK, then the same standards should apply to the flawed Keynesian predictions of 1946.

Tyler Cowen used to argue that 2009 showed that we weren’t as rich as we thought we were. I think 1946 and 2013 (another failed Keynesian prediction) show that we aren’t as smart as we thought we were.

Update: David Henderson has some more observations on this period.