Hindsight is 20-20 (at best)

Update: I see Matt Yglesias beat me to it.

Before criticizing a Paul Krugman post let me praise his recent post on the Chinese yuan. I completely agree that the press is overplaying the IMF’s decision to make it a reserve currency. I did see one report that this might push the Chinese to do more financial reforms, which would be fine. But countries don’t benefit from reserve currency status anywhere near as much as the media would lead you to believe.

In an earlier post Krugman unintentionally insults Dean Baker:

It’s true that Greenspan and others were busy denying the very possibility of a housing bubble. And it’s also true that anyone suggesting that such a bubble existed was attacked furiously — “You’re only saying that because you hate Bush!” Still, there were a number of economic analysts making the case for a massive bubble. Here’s Dean Baker in 2002. Bill McBride (Calculated Risk) was on the case early and very effectively. I keyed off Baker and McBride, arguing for a bubble in 2004 and making my big statement about the analytics in 2005, that is, if anything a bit earlier than most of the events in the film. I’m still fairly proud of that piece, by the way, because I think I got it very right by emphasizing the importance of breaking apart regional trends.

So the bubble itself was something number crunchers could see without delving into the details of MBS, traveling around Florida, or any of the other drama shown in the film. In fact, I’d say that the housing bubble of the mid-2000s was the most obvious thing I’ve ever seen, and that the refusal of so many people to acknowledge the possibility was a dramatic illustration of motivated reasoning at work.

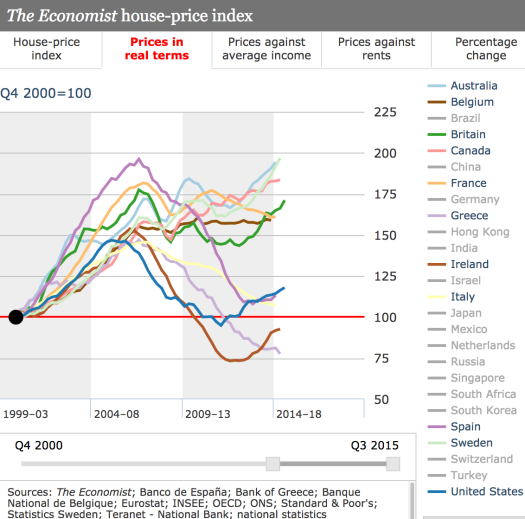

I hear this claim over and over again, and just don’t understand it. First let’s consider the Baker claim that 2002 was a bubble. As the following graph shows, US housing prices are higher than in 2002, even adjusted for inflation. In nominal terms they are much higher. So the 2002 bubble claim turned out to be completely incorrect. Krugman needs to stop mentioning Baker’s 2002 prediction, which I’m sure Baker would just as soon forget.

Of course prices then rose much higher, and are still somewhat lower that the 2006 peak, especially when adjusting for inflation. So I can see how someone might claim that 2006 was a bubble (although I don’t agree, because I don’t think bubbles exist.)

But here’s what I don’t get. Krugman says it was one of the “most obvious” things he’d ever seen. That’s really odd. I looked at the other developed countries that had similar price run-ups, and found 11. Of those 6 stayed up at “bubble” levels and 5 came back down. If they still reported New Zealand it would have been 7 to 5 against Krugman. How can you claim something is completely obvious, when there is less than a 50-50 chance you will be correct? If Krugman were British or Canadian he would have been wrong.

But it gets worse. Almost no one, not even Krugman, thought we’d have a Great Recession. That makes the bubble claim even more dubious. Does anyone seriously believe that the utter collapse of the Greek economy has nothing to do with the decline in Greek house prices? That it’s all about bubbles bursting, with no fundamental factors at all? That seems to be the claim of the bubble mongers. Even in the US, at least a part of the decline was due to the weak economy. No, I’m not claiming all of it, but at least a portion. Look at France, which held up pretty well despite a double-dip recession. You can clearly see the double dip in the French house prices, so no one can tell me that macroeconomic shocks like bad recessions don’t affect house prices.

In conclusion, even ignoring the elephant in the room–the Great Recession–Krugman’s claim that a bubble was obvious makes no sense. Most housing markets didn’t collapse after similar run ups. Most are still up near the peak levels of 2006, even adjusted for inflation (and significantly higher in nominal terms.) But add in the Great Recession, and the bubble claim becomes far weaker.

Of all the cognitive illusions in economics, bubbles are one of the most seductive. But I expect more from an economist who usually sees through these cognitive illusions, and did a good job showing the fallacy of the claim that reserve currencies status has great benefits to an economy.

PS. In case you have trouble reading the graphs, the 5 countries with big drops are the US, Greece, Italy, Spain and Ireland. The US drop is even more surprising when you consider that our post-2006 macro performance is more like the 6 winners. So I could have claimed it was 6 to 1 against Krugman, if I’d put in a dummy variable for “PIIGS” status. Does any bubble-monger know why Australian, British, Belgian, Canadian, French, New Zealand, and Swedish house prices are still close to the same lofty levels as 2006, or even higher? What’s different about the US that made a collapse “inevitable”?

(Paging Kevin Erdmann.)

PS. I also have a post on Krugman over at Econlog, in case you haven’t gotten your fill here.