The long run is now

I recently criticized the view that the Fed might want to consider raising interest rates because a long period of low rates could lead to financial imbalances, such as “reaching for yield.” I actually have several problems with this view, but focused mostly on the implicit assumption that tighter money would lead to higher interest rates. That’s not true over the sort of time frame that people are worried about.

Tyler Cowen linked to the post and offered a few comments:

Scott Sumner dissents on reach for yield. I don’t think easier money will boost the American economy right now. So I think you just get a loanable funds effect and then possibly a reach for yield.

A few reactions:

1. I have a rather unconventional view on the question of policy lags, which Tyler is probably referring to in his “right now” remark. I believe that monetary policy affects RGDP almost immediately, or at least within a few weeks. This is based on three interrelated claims, which may or may not be true:

a. Monetary policy immediately affects expected future NGDP growth. That can be defended either as a definition (I define the stance of policy as expected NGDP growth) or if you prefer it can be defended on EMH/Ratex grounds. If it affected growth expectations with a lag, then there would be lots of $100 bills on the sidewalk. I don’t see many.

b. Changes in expected future NGDP have an almost immediate impact on current NGDP growth. I can’t prove this, and it’s the weakest link in the chain. But I strongly believe it to be true. Someone should do a study correlating changes in expected future NGDP (perhaps 4 quarters forward, consensus forecast) with changes in current NGDP. I expect a strong correlation. Thus during periods where the expected future NGDP falls sharply, such as the second half of 2008, current NGDP also falls sharply.

c. Changes in current NGDP are highly correlated with changes in current RGDP. This is one of those “duh” observations, at least for anyone who pays attention to the data.

Most people believe in long and variable lags, because they associate “monetary policy” with changes in interest rates. If the Fed created and subsidized trading in a NGDP prediction market, I believe we would quickly discover that my view of policy lags is correct, and the consensus view is wrong. But even if I were wrong, wouldn’t it be useful to pin down this sort of stylized fact? You’d think so, but my profession seems surprisingly uninterested in these sorts of things.

2. The loanable funds effect is exactly why I think I’m right. Faster growth would lead to more demand for loanable funds, and thus higher interest rates. I wonder if Tyler is referring to the “liquidity effect”, the tendency for monetary injections to lower interest rates in the short run. If so, I don’t think this effect lasts long enough to justify distorting Fed policy with tight money in order to stop people from “reaching for yield.”

3. I don’t like the term “reach for yield.” When the interest rate falls, it’s rational for people to value any given future cash flow at a higher level. So if rates fall for reasons unrelated to corporate profits or returns on apartments, then stock and real estate prices should rise. That’s markets working the way they are supposed to. I believe low interest rates are the new normal of the 21st century (partly but not entirely for Cowenesque “Great Stagnation” reasons), so I’m not at all concerned by higher asset prices.

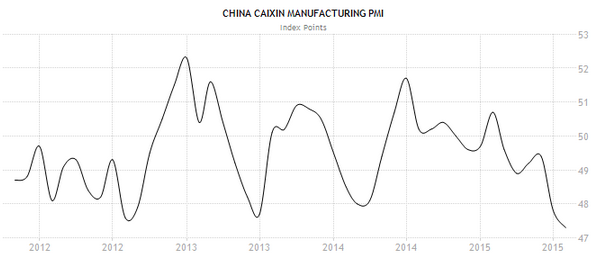

4. Tyler is on record predicting a very bad recession in China, and also for being open to arguments that the Fed might want to consider raising interest rates this year. Each is an eminently reasonable and defensible view. But surely they can’t both be true? If China is going into a very bad recession, I can’t even imagine a scenario where the Fed raises rates and then a year later looks back and says, “Yup, we’re sure glad we raised rates.” Stocks plunged earlier today on just a tiny, tiny piece of bad manufacturing news out of China. How tiny? Notice that the same low PMI occurred three other times in the past 4 years, without RGDP growth ever falling below 7%.

What would that index look like if Chinese RGDP growth was actually about to turn negative? What would US stocks look like?

5. I strongly agree with Lars Christensen’s post, which suggests that the Chinese are making a mistake by trying to prevent the yuan from falling. I also agree with those who claim that recent events show the Chinese leadership to be less competent in economic affairs than many had imagined. This is a consequence of development; the problems become trickier than when you are just cleaning up after the Maoist disaster. They don’t seem to be any better at monetary policy than we are.

6. Off topic, I probably erred in saying Trump has no chance. That’s my personal view, but maybe I’m just an old timer who is out of touch with changes in America. After all, Berlusconi was elected three times in Italy. I saw Trump as just another example of a rabble-rouser like George Wallace or Patrick Buchanan, who rose up and then faded. That’s still my gut level view, but commenter “John” points out that Trump does have a non-zero chance in prediction markets, and I do claim to be an EMH guy. More importantly, even though Trump and Sanders are unlikely to even be nominated, I see their rise as bad news for American politics. I could even see their limited success hurting the stock market slightly, as the prospect for sensible economic and immigration reforms seems ever more distant. Historically, markets do worse in times when the political situation is adrift. And at the moment China, the US and Europe all seem to be a long way from the almost effortless competence of the Reagan/Clinton era.

PS. Japan 2014, Canada 2015. Another fake “recession” call. Read about it at Econlog.

Tags:

1. September 2015 at 12:25

The stock markets are falling because Jackson Hole showed the Fed is still set on actively tighening monetary policy. The market had been hoping for dovishness, but got a “straight bat”. China is a sideshow for the US. The Fed is everything.

The 2015 Hypermind is not a relevant guide anymore. 2/3 of 2015 is history, already. 2016 NGDP Expectations are everything. They are likely weakening so why is the Fed intent on tightening?

1. September 2015 at 12:31

James, In a direct sense China may be a sideshow. But it indirectly reduces the Wicksellian equilibrium rate, which makes any given policy setting in America more contractionary. The market cares about two things, the future path of the policy rate, and the future path of the Wicksellian equilibrium rate.

1. September 2015 at 12:40

I just did some regressions on the Philly Fed data (I’ve done these before and they always show good results). The simplest specification with solid results* was changes in NGDP regressed against two lags of itself, 1 year ENGDP, it’s change, and one lag of the change. All have significant positive coefficients. the Expectations variables are all significant at the 1% level.

I’m not sure how the timing of the Philly Fed survey impacts the ENGDP variable, but the current report has Q3 2015 data even though Q3 NGDP is not yet available, so I would guess that it isn’t a negative.

Intercept -0.001887487

Lag1 0.202810678

Lag2 0.166066145

ENGDP (YoY) 0.187584451

Change 0.349210877

Lag Change 1 0.356017911

*Adjusted R^2 around 50% and all variables significant at least at the 5% level, except intercept

1. September 2015 at 13:30

Another good post. Great link to Lars.

1. September 2015 at 13:41

Thanks John. That result sounds quite interesting.

Thanks Brian.

1. September 2015 at 13:54

Although Tyler is very, very smart, when it comes to highly politicized things like the Fed and what it should do, he cannot help but be an apologist for the right-wing. I am sorry, but when I read his posts about macro, I think his true self comes out. It’s like his brain knows better, but his heart really wants the Austrian-economic theory of business cycles to be correct. He wants to live in a world where countries are punished by deep recessions for not following free market policies and the Fed should raise rates because infla…I mean bubbl…I mean…well just because!!

I see it in so many people who should know better. Just recently Barry Ritholz, a blogger and investment analyst, whom I respect a lot, wrote a column pushing the Fed to raise rates. He is not even particularly right wing, but he trotted out the same old arguments (it’s only a 1/4%, distortion!, bubbles, provide ammo to fight next recession, etc., etc.). It’s depressing to watch people you like being absorbed by the FedBorg. The pull to make a morality play out of economics is incredibly strong.

I submit that instead of economists analyzing economic data to predict the next recession, the best people who can predict the next recessions are psychologists. Or maybe poker players. People who can read what’s on Yellen’s mind. Economic data is only important in the sense of how it might cause Yellen to react. It’s depressing, but this has been the state of affairs for almost 7 years now. I am not a good poker player or reading people, but my instinct says Yellen is about to go full Trichet and repeat ECB’s rate increase in 2011. I sincerely hope I am wrong.

1. September 2015 at 15:05

Liberal, I can’t agree with you there. I’d say that about 80% of the time Tyler and I disagree I am to the right of him. He’s one of the least ideological bloggers I’ve read. Just in recent weeks he’s had stuff on consumption inequality and technological unemployment where my views are probably well to the right of his.

He has a sort of “complexity” approach to lots of issues, whereas I tend to have a simplistic view of macro (it’s all about money and NGDP.) In many areas I think the complexity view is correct, but not macro.

1. September 2015 at 15:26

James Alexander wrote:

“The 2015 Hypermind is not a relevant guide anymore. 2/3 of 2015 is history, already. 2016 NGDP Expectations are everything. They are likely weakening so why is the Fed intent on tightening?”

I don’t think this is quite true. How long did it take for NGDP to plunge by 9% in 2008? If NGDP graw at an annualized 3.6% pace in Q1-Q3, then at 0% in Q4, then NGDP for the full year would be 2.7%, right? If a recession starts *now*, the Hypermind market should still catch it if enough knowledgable people are still trading it.

1. September 2015 at 15:39

Scott,

I have a rather unconventional view on the question of policy lags…This is based on three interrelated claims, which may or may not be true:

“a. Monetary policy immediately affects expected future NGDP growth…”

To the extent that financial market variables such as inflation expectations, bond yields, stock prices and exchange rates are proxies for NGDP expectations then I would say that VAR evidence shows that monetary policy does have immediate effects on NGDP expectations but that it takes up to two months for their full effects to be exhibited. That’s a short lag but it is not nothing.

Is that at odds with EMH? I don’t know. But my feelings about EMH are very similar to David Glasner’s (“much truth” but “conceptual difficulties”):

http://uneasymoney.com/2015/08/30/excess-volatility-strikes-again/

And if a theory is in odds with empirical evidence then (unless I can find a methodological problem with the empirical evidence) I am much more likely to question the theory than the empirical evidence.

1. September 2015 at 15:43

The “low interest rates will cause the economy to collapse, as investors, lenders and borrowers will make very bad decisions,” rests upon a premise of irrational decision-making by major players.

Okay, so let’s construct an economic model where people make irrational decisions…should lead to interesting results…

The motivation behind the tight-money crowd is not found in macroeconomics.

Besides, Scott Sumner and Milton Friedman are right: you cannot tighten your way to higher interest rates, at least not for long.

I posted here recently the agenda of the recent Jackson hold meeting. All six panel presentations were on the topic of inflation and five out of the six were on “inflation dynamics.”

What does that tell you?

The practice of central banking has been reduced to inflation hysteria.

I assume the politics behind the tight money crowd is a desire to tilt the playing field in favor of lenders and employers and away from the employees and borrowers. The old class warfare, but that is really akin to cutting off your nose to spite your face.

1. September 2015 at 15:43

Scott, apparently the BIS is set on “killing” the Wicksellian interest rate!

http://spontaneousfinance.com/2015/09/01/natural-interest-rates-are-dead-the-bis-indirectly-says/

1. September 2015 at 15:51

Scott:

“b. Changes in expected future NGDP have an almost immediate impact on current NGDP growth…”

I find this claim far less controversial than the first. Lars Christensen proxied NGDP expectations with stock prices and exchange rates and found they forecasted future NGDP very well:

http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/09/29/markets-are-telling-us-where-ngdp-growth-is-heading/

Justin Irving ran with that ball a great deal further:

http://economicsophisms.com/2013/01/27/adding-market-expectations-to-our-models/

and found that market based proxies for NGDP expectations forecast NGDP well up to three quarters out.

And (I’ll spare you another link) my Summer of VAR posts at Historinhas show that inflation expectations, bond yields, stock prices and exchange rates each forecast output and/or the price level.

This doesn’t show that NGDP expectations raise NGDP *immediately* but if NGDP expectations forecast future NGDP, it certainly suggests that they at least have an effect on intervening NGDP growth.

1. September 2015 at 16:08

Scott,

“c. Changes in current NGDP are highly correlated with changes in current RGDP…”

I don’t find this at all controversial, but I have found that some self described Post Keynesians (e.g. Unlearning Economics) assert that the causality goes from RGDP to NGDP (Huh?!?). This of course puts them at odds with Keynes and AD/AS (Chapter 3 of the General Theory), but when I point this out they usually respond by stating that they don’t agree with AS/AD. It is at this point I usually ask them why do they even bother describing themselves as Keynesian.

1. September 2015 at 16:17

I’d love to see Trump and Sanders running as independent candidates. That would make for an exciting campaign, indeed. Apparently, Carson has now caught up in Ia. If Trump were to lose either there or in NH, that would give me hope of his imminent demise.

1. September 2015 at 17:59

@scott

Pretty much spot on, but I guess to be precise I would describe it in terms of Fed action having an immediate effect on marginal spending on goods and services by the non-banking sector.

Also you can’t really distinguish between the expectations effect and the asset price effect. Marginal changes in spending are impacted both by asset prices and by NGDP expectations, and they almost always change together. You can think of an asset supply curve (or a goods and services demand curve) where asset price changes cause movement along the curve and changes in NGDP expectations cause a shift in the curve.

IMHO expectations play a bigger role (which is why you often see asset prices dropping with unexpected OMP), but I don’t think the effect of expectations is any more immediate than asset price changes….it’s just a bigger effect.

1. September 2015 at 18:25

Great post, #4 especially.

Scott must be more used to this, to me this is a banging-my-head-on-the-desk moment. How can anyone really believe contractionary monetary policy will raise real or nominal returns? How can anyone seriously advocate for a return to “normal” rates as though markets have no input? How can it not be obvious that expected inflation is a component of interest rates?

On #5, Lars is excellent as usual. China has already spent $200B trying avoid the float, will they empty the reserves?

Watch the reserves. Because of the expectations, this might be a major inflection point for the country. I want to believe and fervently hope the Chinese are not pigheaded enough to keep chasing this dragon, because my bet with Scott is a very small thing next to the welfare of 1.3 billion people.

1. September 2015 at 18:37

Re “Is Tyler Cowen Just A Right-Winger”?

Well…

It is interesting how sporadic urban minimum wage laws are always a topic for Cowen, usually cast in a bad light (I happen to be against minimum wage laws).

But nearly universal (in the U.S.) urban regulations on the use of land, and even those regulations that specify single-family detached residential use only, are never a topic.

Universal (in the U.S.) laws against push-cart vending are never a topic.

I would say the entire “libertarian” or “right-wing” movement in the U.S. (Cowen included) picks its topics with a very PC framework.

The words “malinvestment” and “U.S. national security spending” and never matched, for example.

The VA runs a communist health plan, inside of federal facilities, staffed by federal employees, for the benefit of former federal employees…never a topic.

In this light, Cowen is mostly just a right-winger…but a very nice and smart right-winger.

1. September 2015 at 18:43

If the long run is now, then the long run was always now.

1. September 2015 at 18:54

Because the Fed distorts the economy in the short run, those short run distortions build up until there is a correction in the long run, in which case the Fed could either abstain from continuously accelerating inflation, which has been the case since 1913 and why Sumner believes in the myth that “tight money” is the root cause of recessions, or the Fed could keep accelerating inflation towards hyperinflation.

Sumner still has not answered the question of why it is that on a cycle basis as we have seen, why so many people in separate industries, and now more and more in separate countries, all find it beneficial to radically increase their cash preference, all about the same time, all so pronounced.

Sumner sees falling spending and instead of studying and researching the causes for this, which is in the first place rising cash preference, he instead evades this and like blaming symptoms of cancer on an absence of treating the symptoms, he narrows in on one of the symptoms of rising cash preference, i.e. falling spending, and blames the symptoms of rising cash preference on an absence of treating those symptoms.

Sumner will always be wrong as long as continues to adhere to models I have time and time again shown are flawed. The fact that Sumner keeps repeating the same flawed arguments despite this is proof that truth is not his primary concern on this blog.

1. September 2015 at 18:54

The link to Tyler’s post is going to Lars’ post. Is anyone else seeing the same thing?

Re: Chinese leader’s competence, they’re now focused on the big parade-a big waste of money and time.

1. September 2015 at 21:08

Prof. Sumner, I second David Glasner’s request in the comments he made in the post that Mark Sadowski has linked.

Please write the post / link to the post already written about “what is wrong with the statement – the market can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent”

2. September 2015 at 04:16

@John Hall

You don’t understand why you shouldn’t mindlessly churn out regressions on non-stationary time series, do you?

2. September 2015 at 04:18

Michael, I tend to agree, and obviously the market does not expect a recession right now—neither the bond market nor Hypermind.

Mark, If that’s true then it should be possible to easily get rich by trading on that model. I’m still skeptical, but if you use it to get rich then I’ll re-evaluate that view. 🙂

I responded to David’s post in the comment section.

Marcus, That doesn’t sound too promising.

dtoh, Agree that asset prices generally play a role.

Thanks Talldave.

LC, Thanks, I’ll fix it.

Prakash, I’ll take a look.

2. September 2015 at 06:04

Scott, I don’t know about a recession, but tips are pricing in the risk of a near term deflationary shock.

http://online.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/2_3020-tips.html?mod=mdc_bnd_pglnk

2. September 2015 at 06:14

Kevin, I would ignore TIPS with maturities of less than 5 years, they are distorted by commodity price swings.

2. September 2015 at 06:25

Scott,

Re this and your recent Econlog post about easier money and long-term rates. I’m sure you’ve talked of this before, but the example of Germany may be even better because the ECB already proved out the scenario we’re talking. ECB raised rates in 2011. German 10 year rates fell by 150bps. The race to normalize proved to be anything but.

2. September 2015 at 07:12

Nothing against Tyler on the Chinese turndown but he appears to have a mood afflilation that China should have a massive downturn instead of lowering growth rates or a short term recession which is 2 – 3% growth rates. The big question is whether they choose to allow devaluation with higher inflation or high currency with higher unemployment. (We will see how flexible the Chinese labor market will be.)

Anyway, in terms of Fed action, I still see why the Fed simply dips their toes in reversing QE purchases and lowering the balance sheet.

2. September 2015 at 08:42

@Beefcake the Mighty

This seems like a particularly harsh criticism. You accuse me of not understanding basic time series econometrics based on some quick and dirty results I did in a comment on someone else’s blog?

Re-reading my comment, I think I probably could have done to improve it was corrections for standard errors. I just used normal OLS. So I probably wouldn’t report these results in a journal or something. But a comment to a blog post is not a journal. I don’t feel I need to be up to that standard.

Nevertheless, I do understand time series econometrics, likely better than you do, given the undeserved nature of your criticism. Consider first that the regression is of (log) changes in NGDP. While NGDP has a unitroot, changes in NGDP should be approximately I(0). I then use two lags of NGDP. This basically means I’m estimating an AR(2) model of NGDP changes. This is essentially equivalent to an AR(3) model of NGDP log levels. In other words, I should be accounting for a large part of the non-stationarity of NGDP. That I didn’t include more lags was that they weren’t significant in my relatively simple test.

I then added three additional variables based on ENGDP. ENGDP is a mean-reverting variable, but where the mean changes over time. I didn’t test it for being stationary as it is pretty clearly not I(1). This means that its change and the lag of its change will be I(0).

So my regression basically involved a number of either stationary variables, or variables that can be considered approximately stationary enough for the purposes of a quick and dirty comment on a blog post.

Now, if I were estimating the best model I could think of for NGDP, I probably would have done some things differently. For instance, I could have included additional regressors. Also, I generally find that NGDP is cointegrated with a number of other variables, most notably the labor force. Finally, NGDP tends to be more volatile the higher the growth rate is. However, I did not do these things because I wanted the analysis to focus solely on the things that Scott was talking about: the impact of ENGDP on NGDP.

2. September 2015 at 08:48

Sumner: “This is based on three interrelated claims, which may or may not be true..”, and Sumner precedes to name these claims as if they were laws of nature.

Selected howlers: “monetary policy immediately affects expected future NGDP growth. That can be defended either as a definition (I define the stance of policy as expected NGDP growth) or if you prefer it can be defended on EMH/Ratex grounds.” -oh, really? The observer has a choice eh? But Sumners first ground assumes that a central bank can manipulate NGDP, which is simply not proven, while the second ground assumes the same thing, money non-neutrality. If only the real world was as cooperative.

“Changes in expected future NGDP have an almost immediate impact on current NGDP growth. I can’t prove this, and it’s the weakest link in the chain. But I strongly believe it to be true. Someone should do a study …” – Sumner can’t prove this, acknowledges it’s the weakest link, yet strongly believes it to be true. Makes no sense whatsoever. And if this was so obvious, Sumner’s apt pupil Mark Sadowsky would have done the study Sumner suggests.

“Changes in current NGDP are highly correlated with changes in current RGDP. This is one of those “duh” observations, at least for anyone who pays attention to the data.” – correlated after the fact. The point being: NGDP = RGDP + inflation but only after the fact (after inflation is determined for the year). Before the fact, i.e. on January 1, you cannot tell what changes in NGDP will be, nor changes in RGDP, nor inflation. Hence NGDP = RGDP + inflation is a tautology, like the Quantity Theory of Money, that’s true at all times but only in retrospect, since infaltion is unknown. Simple example: 3 = 1 + 2, 3 = 2 + 1, 3 = 3 + 0, shows NGDP correlates nicely with RGDP, but is worthless as a policy tool since the wild card is inflation.

Sadowski: on NGDP and RGDP correlation “… I have found that some self described Post Keynesians (e.g. Unlearning Economics) assert that the causality goes from RGDP to NGDP (Huh?!?).” – Huh?!? You can yourself and economist and you don’t understand the Real Business Cycle people, nor how money is neutral? You that narrow minded? I guess so.

2. September 2015 at 09:05

@John Hall

You think including more lags “accounts” for non-stationarity? Clueless. You’re a good example of why Excel should put its stats routines in lock-down mode until the user can prove some basic competency.

If you really know so much about time series, put your results together in the form of a paper and post it on SSRN, so others can be the judge. Don’t shoot your mouth off on blogs like you know shit about shit.

2. September 2015 at 09:24

‘ I have found that some self described Post Keynesians (e.g. Unlearning Economics) assert that the causality goes from RGDP to NGDP (Huh?!?). This of course puts them at odds with Keynes and AD/AS (Chapter 3 of the General Theory), but when I point this out they usually respond by stating that they don’t agree with AS/AD. It is at this point I usually ask them why do they even bother describing themselves as Keynesian.’

Mark, ask Unlearning Economics why he doesn’t just call himself a neo-Sraffian.

2. September 2015 at 10:44

@Beefcake the Mighty

As I said before, my comment was just some quick and dirty analysis. How suddenly I don’t know “shit about shit” unless I post it on SSRN is nonsensical. I’m not sure why the burden is on me anyway: your criticism is not specific. You say I don’t understand unit roots, but you don’t say in what way the analysis is wrong. Is it that there is a concern about spurious regression?

Regardless, Scott asked about a particular relationship, I did what I thought was some reasonable analysis quickly that I thought he might find interesting and posted the results.

Moreover, all the data I used is publicly available. If you think my results are invalid, then it is not hard to find the sources (Philly Fed and BEA) and do the analysis differently. If it is so worthy of posting on SSRN, then you can go ahead and do that too. I suspect that you will find that my approach is reasonable and a more sophisticated analysis doesn’t change the general thrust of it.

For instance, I found my results from yesterday and double-checked that the residuals have basically no correlation with lagged residuals (one period).

Also, I mentioned the lags and AR models because there is significant evidence of serial correlation in NGDP. I tend to think of stationarity and serial correlation jointly. For instance, if you fit log equity prices with an AR(1) model, then you’ve effectively difference the series. The residuals are both stationary and not serially correlated. An AR model is just a more general way to difference.

I was using percent changes in NGDP. I was operating under the assumption that percent changes in NGDP are stationary. This is a pretty standard assumption. I typically don’t need to do an ADF test in this case because it’s pretty obvious. I did one anyway, for you, and the t-stat is like -9.

2. September 2015 at 11:19

Ray,

Why do you waste time on this site if you believe money is neutral? NGDPLT can’t do any harm if money is neutral. Are you worried that Scott might influence the Fed to waste paper?

2. September 2015 at 11:28

http://www.pragcap.com/why-expectations-based-econ-models-dont-work/

Another viewpoint on the problems associated with relying on expectations and forecasts.

2. September 2015 at 12:08

Bloomberg is reporting a substantial tightening of global monetary policy even prior to Federal Reserve action:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-02/welcome-to-quantitative-tightening-as-12-trillion-reserves-fall

The article also attributes recent market headwinds to this monetary policy tightening.

2. September 2015 at 16:27

Ray, Money affects NGDP and this shows non-neutrality? Hmm, I’ve never seen that claim before.

Trevor, Yes, I see slight tightening, but not too much yet.

2. September 2015 at 19:57

Sumner: “Ray, Money affects NGDP and this shows non-neutrality? Hmm, I’ve never seen that claim before.” – did I say that? I am commenting on what you and Sadowsky are saying.

2. September 2015 at 20:16

Intellectuals really seem to hate this Trump guy. This reminds me a lot of George W. and even more so of Reagan.

In 1980 most intellectuals and media outlets assured the American voter again and again that Ronald Reagan is a mindless clown. Unqualified. Dangerous. Hopeless. Unpresidential. A ridiculous buffoon that should never be elected. If elected this would mean nothing less then the end of the world. Luckily the American voter did not agree.

I’m really sceptical when all the media outlets run in the same direction. They are usually wrong when they do so.

I’ll give you an example. During the debate on Fox it was Trump who had the best ideas on healthcare compared to all the other GOP candidates. Matthew Yglesias thought so, too.

http://www.vox.com/2015/8/7/9116127/donald-trump-insurance-regulation

3. September 2015 at 05:06

ECB cuts forecasts for growth and inflation

http://www.theguardian.com/business/live/2015/sep/03/markets-european-central-bank-mario-draghi-inflation-live

3. September 2015 at 05:47

Buchanan is not a rabble rouser. If that’s his reputation it’s because both parties have been slandering him for 20 years, mostly because where clear-cut verdicts have been obtained he’s been right about most everything. Or because people automatically equate certain policy positions like immigration restriction with rabble rousing, as if a consequentialist case for it is impossible.

Most of Buchanan’s recent columns are denunciations of the Left for rabble-rousing on racial issues, and of the Right for demagoguing on the Iran deal.

You can get a good sense of Buchanan’s decency from the Ali G interview w/ him, where Buchanan’s continually asked about “where are the BLT’s in Iraq!” and Buchanan decides rather than to embarrass this unfortunate guy by explicitly correcting him, he simply corrects BLT to WMD when referring to it in his answers.

Trump’s nothing like Buchanan.

3. September 2015 at 05:48

I think the “reach for yield” argument (as I have heard it, and put into some level of rigor) goes something like this: If (nominal) risk free rates are low, investors will invest in very risky securities in order to increase their expected spread and keep their expected nominal yields constant. Why would they do this? Some investors have nominal targets that they want to reach; e.g. pension funds typically set their asset return assumption long ago and rather than adjust it to a new, low return environment, will change their asset allocation to move into riskier assets so they can still justify that expected return. Or people just get used to historical “S%P 500 should earn me 10%/year” and convince themselves that if the only thing that affords a 10% return in front of them are small cap Greek stocks, then they really aren’t any more risky than the S&P 500 has been historically. It’s not dissimilar to the nominal problem with employment and sticky wages, just I guess you could call this the “sticky yield” problem.

Why is this a problem? 2 problems. First, in the short to medium run, if before ZIRP there are lots of people who want (some portion of their portfolio) to return 6%, then the market of assets that return 6% will grow so that there will be lots of ways to make a 6% yield (huge long term Treasury market, Agency Mortgage backed securities, high quality corps, etc). But when those assets reprice to yield 4% in ZIRP (assuming their risk hasn’t changed at all – the drop in yield is simply due to the lower risk free rate), but the universe of investors that want to yield 6% doesn’t change as much due to the nominal rate problem described above, then the much smaller universe of assets that used to yield 8% and now yield 6% can’t absorb all the new buyers, and gets bid up even more, making it even more difficult for investors to earn the nominal rate that they are locked into.

Second, the new set of assets that earn a nominal rate or 6% might look very different from the old assets that earned 6%, and will probably require a higher level of scrutiny and sophistication that the investors locked in at a 6% preference might not have. Either they are naturally more risky securities that require more care to understand, or they are constructed to have a higher yield but might just be pushing that risk out into the tail.

3. September 2015 at 07:25

Ray, You said:

“But Sumners first ground assumes that a central bank can manipulate NGDP, which is simply not proven, while the second ground assumes the same thing, money non-neutrality.”

Care to explain? M affecting NGDP is the “same thing” as money nonneutrality?

Christian, Yglesias is a smart guy; I’m sure in private he views Trump as a clown. Some clowns have quite sensible views on health care.

If I have to explain to you why Trump is a clown than there’s no point I continuing the conversation. This isn’t rocket science.

Brendan, So I have people defending Trump and then Buchanan. Where can I get a new group of commenters?

Njnnja, You said:

I think the “reach for yield” argument (as I have heard it, and put into some level of rigor) goes something like this: If (nominal) risk free rates are low, investors will invest in very risky securities”

I know what people mean, but they should not talk about the public as a whole buying stocks (every purchase is a sale), they should talk about stocks being valued at a higher level, which is of course entirely appropriate when rates fall and expected cash flows are unchanged.

The rest of your comment makes no sense. Sticky yields? I don’t see a shred of evidence for that. It’s safest to stick with the EMH, unless you have strong evidence for an alternative. In any case, this is finance, which has nothing to do with monetary policy.

3. September 2015 at 09:24

Thanks for the response but I’m just trying to reconcile your views, with the “folk monetary theory” that seems to be motivating the market. There are plenty of smart people in finance who are absolutely convinced that the “reach for yield” is (was?) happening and that investors very much want the Fed to raise rates because they believe that rates of return on other assets will increase when that happens.

It’s not just about stocks going up, its things like CLOs and student loans, where everybody *knows* they are overvalued but keep buying them anyways because anything else provides too low a rate of return. And every trader believes that they can “trade out” of the position before prices crash (which will happen, so the theory goes, when yields on more “attractive” asset classes go back up when ZIRP ends).

So while I know the singular of data is not anecdote, if you are looking to the market (i.e. EMH) for predictions, that’s what it seems to be thinking.

3. September 2015 at 11:38

I know why you think he’s a clown so don’t tell me. What I’m saying is: I became really careful with these kind of harsh judgments over the years. I feel bad when everybody is doing it. I started reading this blog because people were trash-talking your ideas. Those trash-talkers turned out to be wrong. I gave Ronald Reagan as another example. The West German media outlets trash-talked all his life and never said sorry – until this very day.

There’s a saying in Germany: “You don’t eat a soup as hot as you cook it.” Meaning: Things are rarely as bad as they seem. This applied to Reagan and in my opinion it also applies to Trump. Trumps is putting up a huge populist show. Nothing less, nothing more. There are many examples in American history who did exactly the same thing. Andrew Jackson and FDR come to my mind first.

There’s another saying in Germany by a famous psychiatrist. It goes like this: “We treat the wrong people. Crazy people are not the problem, sane people are.” One meaning is: Listen to “crazy” people from time to time. Try new things. Don’t do the same thing over and over again (another Bush, another Clinton) and expect a different outcome.

Another recent example would be: Make Scott Sumner head of the ECB or the FED. This seems like a really, really crazy idea to the current elite (at least as crazy as Trump as president) – but nevertheless it would be the right thing to do.

Now I don’t know about Trump. But: People should not be so harsh. They should not judge somebody so early and based only on an artificial image shaped by the media when in fact no one can seriously tell how a president Trump would be. Clinton and Bush are easy to predict because they are regarded as sane. I can’ tell about Trump, because Trump is what Germans would call a “Wundertüte” – a bag full of wonders.

3. September 2015 at 11:42

Scott,

Humans have a remarkable ability to rationalize as normal the unpredictable world in which we live. Consider this report of a “mobile home” in Vancouver selling for a million dollars. Is this normal? Maybe. But what is the uncertainty of such a house retaining its value over time? Is this uncertainty reflected in the financing of the house? What happens to the economy of Vancouver and the health of Canada’s financial industry if the model used to justify loans on million dollar mobile homes is horribly wrong?

She paid $1 million for a three-bedroom fixer-upper that she figures will need $200,000 in renovations. “It literally looks like a mobile home dropped on a slab,” admits Whyte. “It’s not your dream house.”

http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/house-hunters-make-personal-pleas-in-hot-markets-1.3209873

3. September 2015 at 12:32

Christian: Very interesting point. What was once called the establishment is worried about Trump because he raises issues it would prefer not to be addressed and because his basic message is that Bush/Clinton/Biden/the Fed/the Pentagon/the Ivy League system don’t have the answers. Ross Perot once rattled the establishment by wanting to talk about protecting the U.S. industrial basis.

Dan W: The problem there is that loans are being used now to buy financial assets — defining that mortgage as a financial asset because the value to the buyer is that he believes he can sell at a higher price. It’s just a leveraged buy. So two problems result — the public is on the hook if the loan goes bad, and the money created by the loan does little public good, compared to a business borrowing to invest in future productivity.

3. September 2015 at 17:49

Charlie,

I agree about the problem. Well actually, the problem is not the use of debt to monetize assets but that the debt is not being correctly priced. Some blame “reach for yield”. That is a factor. But the larger one is government policy which only gives lip service to the principles of capitalism. For when the call for credit comes, and it always does, the government has shown that it will step in and save the bankers from the cost of making their bad debt whole.

This trust in government intervention results in a type of “crony capitalism” where financial institutions privatize profits but socialize losses. Firms, believing a bailout will come when needed, underestimate the true cost of debt and overestimate the value of assets. When this imbalance shows cracks the firms cry for government accommodation that will sustain the mirage of financial strength.

At best an NGDP regime would have a neutral impact on the financial system – being neither better or worse than current Fed methods. At worst an NGDP regime would pour gasoline on the fire of ever inflated asset prices, making the problem worse and creating the setting for an even greater financial and economic dislocation.

3. September 2015 at 23:05

Charlie,

don’t get my wrong. I’m totally against Protectionism. I’m just saying portraying Trump as an idotic lunatic clown is harsh, rash and way too easy. Campaigning is not reigning (Can you say that? Google says no.) No one can tell what a president Trump would actually do.

Reagan said a lot of stuff during his campaign, too. Then when he was elected it happened quite often that Reagan ended up doing quite the opposite. Not because he was a liar but because he thought things through after the election, got good advisers and listened to reason.

Dan,

“At worst an NGDP regime would pour gasoline on the fire of ever inflated asset prices, making the problem worse and creating the setting for an even greater financial and economic dislocation.”

That’s a good point. So far I’ve never really grasped why this should not be a problem. As far as I can tell Mr. Sumner would say something along the lines of: “Asset prices are not inflated. They should be this high or even higher.”

I don’t really buy it. But I can’t prove him wrong. It’s only my intuition. And intuition in economics can be very misleading.

4. September 2015 at 04:45

Christian,

It is good science to test all sides of a question. It is also good science to give consideration to every factor that has influence on the topic being considered. Richard Feynman explained it this way: “the idea is to give all of the information to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not just the information that leads to judgment in one particular direction or another.”

Sumner has every right to theorize that asset prices should be higher. But he then has a responsibility to explain the risks. Advocates of NGDPLT are so very vocal about the benefits. They are peculiarly silent about the risks. Faster growth is desirable. We should test assumptions that limit growth. But we should not dismiss out of hand the reasons growth is not as fast as desired simply because we don’t like the answer!

One can construct a model of highway traffic and show that the ideal vehicle speed is infinite. If one assumes there are no disturbances to the flow of cars then there is no limit (save the physical limitation) to how fast the cars can safely go while maintaining proper braking distance. But the ideal model does not represent reality. In the real world there are disturbances and distractions and these greatly reduce the optimal, safe, driving speed.

The challenge for NGDPLT advocates is not to argue their methodology works in an ideal world. It is not to argue that it solves the economic and financial problems of the past. Their challenge is to demonstrate some humility in explaining how the plan will operate in world of imperfect knowledge and inefficient systems. For all systems of men will fail. It is only a question of how and what damage such failure will cause.

4. September 2015 at 07:09

Njnnja, Don’t confuse market beliefs with views of people that trade in the market. The stock market is strongly opposed to a rate increase, whereas most Wall Street types when interviewed favor higher rates.

Christian, You said;

“Trump is putting up a huge populist show.”

That’s exactly my view. Maybe we are talking past each other. He’s acting like a clown. Whether he really is a clown is another story, maybe he’s just an actor.

And yes, I recall that the Germans thought Reagan was naive when he said “tear down this wall.” I remember that very well.

Dan, Don’t be naive, she paid a million dollars for the land, not the house. There are lots of places all over the world where land is worth that much. I’d pay a million dollars for a mobile home in West LA right now, it it sits on a half acre lot. I have my checkbook out and ready. Two million in Hong Kong.