Hindsight is 20-20 (at best)

Update: I see Matt Yglesias beat me to it.

Before criticizing a Paul Krugman post let me praise his recent post on the Chinese yuan. I completely agree that the press is overplaying the IMF’s decision to make it a reserve currency. I did see one report that this might push the Chinese to do more financial reforms, which would be fine. But countries don’t benefit from reserve currency status anywhere near as much as the media would lead you to believe.

In an earlier post Krugman unintentionally insults Dean Baker:

It’s true that Greenspan and others were busy denying the very possibility of a housing bubble. And it’s also true that anyone suggesting that such a bubble existed was attacked furiously — “You’re only saying that because you hate Bush!” Still, there were a number of economic analysts making the case for a massive bubble. Here’s Dean Baker in 2002. Bill McBride (Calculated Risk) was on the case early and very effectively. I keyed off Baker and McBride, arguing for a bubble in 2004 and making my big statement about the analytics in 2005, that is, if anything a bit earlier than most of the events in the film. I’m still fairly proud of that piece, by the way, because I think I got it very right by emphasizing the importance of breaking apart regional trends.

So the bubble itself was something number crunchers could see without delving into the details of MBS, traveling around Florida, or any of the other drama shown in the film. In fact, I’d say that the housing bubble of the mid-2000s was the most obvious thing I’ve ever seen, and that the refusal of so many people to acknowledge the possibility was a dramatic illustration of motivated reasoning at work.

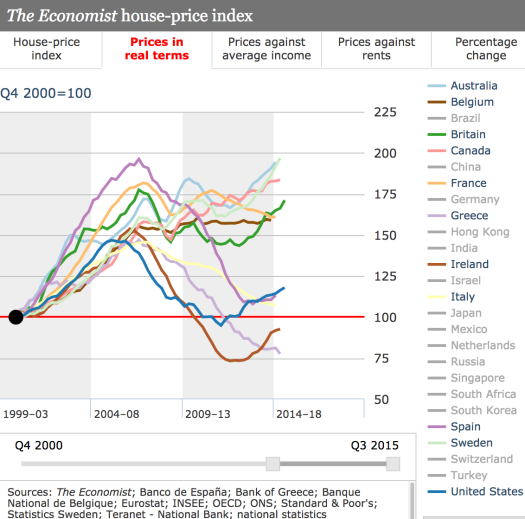

I hear this claim over and over again, and just don’t understand it. First let’s consider the Baker claim that 2002 was a bubble. As the following graph shows, US housing prices are higher than in 2002, even adjusted for inflation. In nominal terms they are much higher. So the 2002 bubble claim turned out to be completely incorrect. Krugman needs to stop mentioning Baker’s 2002 prediction, which I’m sure Baker would just as soon forget.

Of course prices then rose much higher, and are still somewhat lower that the 2006 peak, especially when adjusting for inflation. So I can see how someone might claim that 2006 was a bubble (although I don’t agree, because I don’t think bubbles exist.)

But here’s what I don’t get. Krugman says it was one of the “most obvious” things he’d ever seen. That’s really odd. I looked at the other developed countries that had similar price run-ups, and found 11. Of those 6 stayed up at “bubble” levels and 5 came back down. If they still reported New Zealand it would have been 7 to 5 against Krugman. How can you claim something is completely obvious, when there is less than a 50-50 chance you will be correct? If Krugman were British or Canadian he would have been wrong.

But it gets worse. Almost no one, not even Krugman, thought we’d have a Great Recession. That makes the bubble claim even more dubious. Does anyone seriously believe that the utter collapse of the Greek economy has nothing to do with the decline in Greek house prices? That it’s all about bubbles bursting, with no fundamental factors at all? That seems to be the claim of the bubble mongers. Even in the US, at least a part of the decline was due to the weak economy. No, I’m not claiming all of it, but at least a portion. Look at France, which held up pretty well despite a double-dip recession. You can clearly see the double dip in the French house prices, so no one can tell me that macroeconomic shocks like bad recessions don’t affect house prices.

In conclusion, even ignoring the elephant in the room–the Great Recession–Krugman’s claim that a bubble was obvious makes no sense. Most housing markets didn’t collapse after similar run ups. Most are still up near the peak levels of 2006, even adjusted for inflation (and significantly higher in nominal terms.) But add in the Great Recession, and the bubble claim becomes far weaker.

Of all the cognitive illusions in economics, bubbles are one of the most seductive. But I expect more from an economist who usually sees through these cognitive illusions, and did a good job showing the fallacy of the claim that reserve currencies status has great benefits to an economy.

PS. In case you have trouble reading the graphs, the 5 countries with big drops are the US, Greece, Italy, Spain and Ireland. The US drop is even more surprising when you consider that our post-2006 macro performance is more like the 6 winners. So I could have claimed it was 6 to 1 against Krugman, if I’d put in a dummy variable for “PIIGS” status. Does any bubble-monger know why Australian, British, Belgian, Canadian, French, New Zealand, and Swedish house prices are still close to the same lofty levels as 2006, or even higher? What’s different about the US that made a collapse “inevitable”?

(Paging Kevin Erdmann.)

PS. I also have a post on Krugman over at Econlog, in case you haven’t gotten your fill here.

Tags:

3. December 2015 at 11:53

Funnily enough, I find it more plausible to argue there was a negative bubble in US house prices, that is only slowly bursting. (The metaphors just don’t work in reverse.)

3. December 2015 at 11:56

I mean, with long-term interest rates slowly falling, the fundamental value of any long-lived asset, like houses (or the land they sit on) should be rising too.

3. December 2015 at 12:02

As far as NZ is concerned, two significant factors are involved – (i) very strong immigration flows, mostly to Auckland and (ii) planning restrictions in Auckland that strongly impede the construction of new homes. Not too much of a mystery.

3. December 2015 at 12:27

Since you mentioned Erdmann, this is the most interesting post of his that I’ve come across:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/10/housing-series-part-76-there-are-two.html

3. December 2015 at 12:29

Meant to post this one:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/housing-series-part-77-housing-is.html

3. December 2015 at 12:32

Mark Thomson: if NZ rents have been rising in roughly the same proportion as house prices (so rent/price ratios stay the same), then immigration and planning restrictions would explain it all. But if the price/rent ratio is rising, that suggests falling interest rates.

3. December 2015 at 12:43

Scott — Dean Baker actually had a very recent post about this here:

http://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/asset-bubbles-that-move-the-economy-are-easy-to-spot

(btw — one must remove the “www.” from Krugman’s link to Baker’s 2002 piece. If not, the browser isn’t loading the page properly.)

3. December 2015 at 12:46

I don’t like the term bubble either because it is over used. Any market that looks pricey, usually relative to historical norms of some kind, gets the label. I’ve been trading markets for a long time and true bubbles – if they really do exist – are rare indeed. And you don’t find them in the numbers usually although the late 90s tech bubble might be an exception. I say might because there was some probability – small admittedly – that it made sense to pay hundreds of times earnings for some of the tech companies, especially considering that stocks are very long duration assets. The point is that prices always make some kind of sense at the time; it is only later when conditions change that prices don’t make sense.

But…I do think there are times when a bubble can be identified based on human behavior. At times, large numbers of people do really stupid things chasing easy money. They just become overwhelmed by greed. Two examples. In the late 90s I remember reading an article about people quitting their jobs to day trade. These were not sophisticated investors with some kind of advantage in the market. They were ordinary people who had simply lost their minds. When I first got in the investment business, my mentor told me to never bet the milk money on the market and here were people doing exactly that. It was crazy. Second example. I live in Miami, where condo mania was particularly rampant in the last decade. I knew we were in a bubble when I saw a picture on the front page of the Miami Herald of hundreds of people camped outside in the middle of a tropical storm for a chance – just a chance – to buy a pre-construction condo. I think that was in 2006 but I can’t say for sure. Greed does strange things to people.

My point is that the term bubble applies to a particular type of behavior, not a particular price or valuation. To claim, as Krugman does, that one sees a bubble in some market from looking at data is just plain BS.

3. December 2015 at 13:03

Nick,

The high P/R ratio may be influenced by local supply constraints. Where there is persistent rent inflation, rent levels would only reflect current housing supply & demand, but prices would reflect those future expectations. This effect is even stronger in places like San Francisco where rents have reached the upper limits of affordability, and trigger a persistent in-migration of high income households and out-migration of low income households. That means that, relative to the incomes of the current residents, home prices would be even higher, because they not only reflect higher rents in the future, they reflect a future local population with higher potential rents because of higher incomes.

Here are a couple of (admittedly long) posts on the topic:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/housing-series-part-88-supply-demand.html

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/housing-series-part-89-low-interest.html

3. December 2015 at 13:29

Interesting post, Dilip. Baker says his 2002 call was spot on, even though future price changes didn’t confirm it, because he had the fundamentals right. Prices were rising even though “rents had gone nowhere”.

Here is a graph comparing core inflation with both national shelter inflation and with rent inflation in Washington, DC, where Baker resides.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=2NYQ

Baker says that his 2010 warnings were also correct, but that home prices have risen since then because of……austerity. He says that prices in Washington, DC are unsustainable and the high rate of new building will eventually pull down rents and prices.

Here is a graph of housing permits, using labor force to normalize rates, for the US and for Washington, DC.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=2NZ3

Baker ends on a hopeful note:

“But I really don’t want people to take my advice on this one. After all, as long as the market for condos stays hot, builders will put up more units. Eventually the bubble will burst and the builders still holding unsold units or in the process of constructing them, along with the recent buyers, will take a beating. But this should mean that the abundance of units on the market will make prices more affordable for everyone else. Given the current state of national politics, this may be the best hope for any sort of downward redistribution on the horizon.”

If only we had followed that plan in 2006-2008, instead of creating a premature housing bust that pushed rents higher. (Notice rent inflation in 2006 and 2007 in the first graph. Strange for a housing bubble to burst by having housing starts burst first, followed by 2 years of sharply rising rent inflation.) Can we get policymakers to promise this time they will let the “bubble” burst by creating excess supply that will lead to falling rents? Will Baker stand by that closing statement?

3. December 2015 at 13:33

Let’s also recall that (almost?) 100% of the bubble mongers in 2006/2007 said, “house prices will collapse when interest rates RISE”. That’s a corollary to them not seeing a Great Recession as you’ve noted. I’ve engaged with Baker in his comment section stating exactly what you said about August 2002 being a bubble (his paper said, I believe, that prices then would fall 11% to 22%). His response was that he had no way of knowing that interest rates would be so low now. For a smart guy, that’s a pretty stupid response.

3. December 2015 at 13:48

Kevin: agreed. Expected future rents matter too. But then you would need an increased (expected) *growth rate* of population to get an increase in price/rent ratios. Not sure if that’s plausible.

Like Joseph, I tend to look for clues other than just prices. We do see foolish fads (like “moral panics”) in human behaviour in areas that have nothing to do with markets.

3. December 2015 at 13:52

Dear Commenters,

Could someone please explain why long-term yields surged dramatically higher in both Germany and in the United States?

3. December 2015 at 14:02

Lots of good comment. Travis, I’ll answer your question as soon as someone explains it to me. I suppose less QE than expected, but it seems like an awfully long time for a liquidity effect to last.

3. December 2015 at 14:08

Scott — I’d recommend the comments for a blog post remain topical and relevant to the post in question. I don’t think you want to use it as a general Q&A forum like TravisV seems to do every now & then. Not a knock on him but pretty soon the comments section starts branching in several different directions and its hard to keep track of exactly what it is your post was supposed to accomplish. (esp. for laymen like me)

3. December 2015 at 14:42

Dilip,

Apologies that I’m a distraction sometimes. The commenters here are unusually smart, so I like to get their take sometimes, especially when there’s major news like today’s re: long-term interest rates.

Anyway, whenever there’s a new post here, I try to avoid being one of the early commenters so I don’t distract from the topic too much. But if lots of comments have been posted, then sometimes I go off-topic.

That approach generally seems to work fairly well.

3. December 2015 at 14:47

Dr Sumner said: “Does any bubble-monger know why Australian, British, Belgian, Canadian, French, New Zealand, and Swedish house prices are still close to the same lofty levels as 2006, or even higher? What’s different about the US that made a collapse “inevitable”?”

With no intent to troll, I have to say that this sounds a lot like an argument against the existence of bubbles that is being made by reasoning from a price change. If the Michael Lewis “Big Short” tale is correct, the run up in US house prices was driven by increased demand that was in turn driven by a rapid expansion of credit enabled by mortgage securitization and related big changes in the finance industry. There are similar stories for Greece and Spain where the rapid expansion of credit was a side effect from the creation of the Euro zone. Claims have been made that the mortgage markets in Canada were less prone to the problems seen in the US. https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/econ_focus/2013/q4/pdf/feature2.pdf

I know this is hardly a complete explanation but, It really seems like there is more to the house price story than: markets go up, markets go down, that’s what they do.

I’m not claiming that bubbles exist or that Baker and Krugman predicted things correctly but, if price movements alone don’t tell you much then they don’t tell you much either for or against the existence of bubbles.

3. December 2015 at 15:35

Nick, since those cities can’t add much population, there are two effects. One is that firms which tap into the highly valuable professional networks there have less competition, as do their workers, so incomes in those cities rise, allowing rents to rise. Also, the migration out of low income households also allows rents to rise. There is a marked development since 1995 of cities with high incomes, high rent/income, and high price/rent. The scatterplots over time look like a fungus shooting out spores. I think the housing thing actually explains a lot of the income patterns. The income inequality is almost all from a few counties. Housing is where limited access is creating these signatures of income and wealth distribution, even pushing up profits and nominal wages at tech firms. Look at the scatterplot at the end of this post. Recent income patterns are geographically limited and extreme, and did not exist before the mid 1990s. The 1995 scatterplot is similar to the 1979 scatterplot.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/housing-series-part-80-measuring-real.html

3. December 2015 at 16:12

@TravisV

Yield curve in Bunds flattened, at least at the moment I looked at it, I guess the simple fact that it became less negative in the short end made the entire curve go up.

The dollar fell (against oil, gold, Euro and the Real, for a change), and the yield curve steepened, it looks like compared to the EZ, policy stance in the US was less tight than before …

3. December 2015 at 17:40

Scott, did you see my comments on that Marginal Revolution post on 1177 BC? If so, did you learn anything from them? Tyler deleted them all, so the comments section on MR is a dangerous space for my comments.

3. December 2015 at 18:01

“If they still reported New Zealand it would have been 7 to 5 against Krugman. How can you claim something is completely obvious, when there is less than a 50-50 chance you will be correct?”

“Does any bubble-monger know why Australian, British, Belgian, Canadian, French, New Zealand, and Swedish house prices are still close to the same lofty levels as 2006, or even higher? What’s different about the US that made a collapse “inevitable”?”

-Baker wasn’t just looking at prices. That would be stupid and reasoning from a price change. No, he looked at occupancy rates and other stuff that he thought would have some effect on housing prices in the future. Again, just looking at prices is stupid and unreasonable.

Sweden has legit Soviet-style housing shortages. High housing prices aren’t a luxury there; they’re a necessity.

“But it gets worse. Almost no one, not even Krugman, thought we’d have a Great Recession.”

-I did, but after the recession officially began and before May 2008.

“That makes the bubble claim even more dubious. Does anyone seriously believe that the utter collapse of the Greek economy has nothing to do with the decline in Greek house prices?”

-Clearly, the falling nominal and real demand for Greek housing worsened the Greek economy.

“You can clearly see the double dip in the French house prices, so no one can tell me that macroeconomic shocks like bad recessions don’t affect house prices.”

-Correlation is not causation. How do you know this isn’t just falling nominal and real demand for housing leading to a weaker economy?

“But add in the Great Recession, and the bubble claim becomes far weaker.”

-Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe changing relative housing prices would have caused financial collapse and a Great Recession even in the absence of an NGDP shock.

3. December 2015 at 18:02

Kevin: that last scatterplot is indeed interesting. “Something’s happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear”.

3. December 2015 at 18:52

In Washington, DC, the source of economic rents is not housing, so, there, there is rent inflation, as households bid up the housing stock as their incomes rise, but they keep rent at a comfortable portion of their incomes.

But, the crazy thing about those other cities is that rent, as a proportion of income, has increased as incomes in those cities have shot up above the national norm. Before 2007, cities with moderate incomes did not experience rising rents. This was a phenomenon limited to cities with rising incomes. I think this points to housing as the source of the limited access to the economic rents that are creating those unusually high incomes.

Sorry to flood the comments here with self-references, Scott, but I feel like I have really gotten at this topic recently.

Here is one more:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/housing-series-part-85-housing-prices.html

The idea that rising home prices were not related to rising rents is a widely held belief about the boom that simply doesn’t hold water. But Dean Baker isn’t the only one making that mistake. In the post I linked to here, the San Francisco Fed specifically rejected the rational expectations model as an explanation for the boom because it would have called for rent and prices to be related, and chose a demand-based explanation because it doesn’t. As I point out in the post, this is the San Francisco Fed. This error is so deeply ingrained in our mutually accepted assumptions that the people who wrote that paper that rejected ratex were going home at night to ground zero for the problem of high rents and high prices.

3. December 2015 at 19:08

It’s uncanny that Sumner and Yglesias wrote almost exactly the same piece so close to one another….Groupthink, great minds think alike, or coincidence?

The attempt by Erdmann to square the circle is amusing. Keep it going Kevin, you are a lovable crank.

The DC exception to the rule is real: DC real estate (that’s how my family got into the 1%) is tied to the ‘Capital Effect’ which is the tendency of capitals worldwide to appreciate in real estate due to increased government in the last two generations. Not sure it applies to Canberra, Australia, or Brasilia, Brazil, but it should. Thus when we bought in 2006 in DC, at the top of the market (as Yglesias wishes he had he says), we are ahead today, after a slight decrease in 2008. But if you bought in Arizona or Nevada or Florida, if it’s not prime, likely you’re behind today. Prime means it’s hard to get zoning approval for building a new home and/or the land is not available (Houston prime spots). Finance did indeed enable the price run-up, but to be fair it was not just Wall Street but people who lost money in the dot.com crash trying to score big on the next (obvious) bubble. And bubble does not mean the price stays down forever. I’m sure that in the future, if not already now, the nominal price of Dutch tulips will exceed whatever ‘bubble’ price they had in the 1630s.

3. December 2015 at 20:11

Garrett, Yes, that post by Kevin is excellent–I encourage people to read it (and also the one’s Kevin links to.)

Captain, You said:

“I’m not claiming that bubbles exist or that Baker and Krugman predicted things correctly but, if price movements alone don’t tell you much then they don’t tell you much either for or against the existence of bubbles.”

In my view the burden of proof is on the person making the bubble claim. Either it has useful information about the future level of prices, or it doesn’t. I say it doesn’t. We can get into a metaphysical debate about whether bubbles exist, but I don’t see much evidence that it’s a useful hypothesis.

I occasionally look at LA house prices, which seem completely insane to me. But if someone tells me it’s a “bubble”, then how does that information help me? We can already see lots of examples where prices rise still higher, and stay higher, even after people cry “bubble.” So what good is the hypothesis?

Ray, This post is about the real prices of houses, not nominal prices of tulips.

3. December 2015 at 20:27

E. Harding, Did not read them, but I did leave my own comment at MR.

You said:

“Baker wasn’t just looking at prices. That would be stupid and reasoning from a price change. No, he looked at occupancy rates and other stuff that he thought would have some effect on housing prices in the future. Again, just looking at prices is stupid and unreasonable.”

I don’t care what he looked at, he was clearly wrong.

You said:

“Clearly, the falling nominal and real demand for Greek housing worsened the Greek economy.”

That misses the point. If the eurozone doesn’t collapse, then neither does Greece. Maybe a recession at worst. And did the housing bubble predictors tell us that Greek NGDP would collapse?

You said:

“Correlation is not causation. How do you know this isn’t just falling nominal and real demand for housing leading to a weaker economy?”

Because central banks control NGDP. Have you forgotten what Trichet did in 2008? And then what he did again in 2011? He tightened monetary policy.

You can be a “concrete steppe” person, or a MM, but you can’t be neither. The ECB tightened under either criteria.

You said:

“Maybe changing relative housing prices would have caused financial collapse and a Great Recession even in the absence of an NGDP shock.”

This is the theory that if you shoot someone who has pneumonia with a gun, it doesn’t hurt them, because the real problem is the pneumonia. Actually, gunshot wounds still hurt. We know roughly how much damage big NGDP declines do to non-housing industries, and we know that they do that damage regardless of whether or not housing is also in trouble.

3. December 2015 at 20:59

@sumner

Well, I’m definitely not a concrete steppe person.

“That misses the point. If the eurozone doesn’t collapse, then neither does Greece.”

-Strongly doubt that. The next hardest-hit mainland country, Portugal, suffered less than a 9% secondary-recession RGDP loss. Greece had a near-continuous collapse resulting in 20+% RGDP loss with, unlike in the U.S. Great Depression, little deflation.

“And did the housing bubble predictors tell us that Greek NGDP would collapse?”

-Some did, I’m sure, but I’m also sure that, no matter the reasoning, you would ascribe the hit to random chance.

“Because central banks control NGDP. Have you forgotten what Trichet did in 2008? And then what he did again in 2011? He tightened monetary policy.”

-I look at central bank targets as the actual standard of tight or loose money, so I count 2008 as a negative (though Trichet did no worse than Bernanke there), and see no mistake of Trichet in 2011. Only of Draghi, later.

“Because central banks control NGDP.”

-But couldn’t this be a sort of 1997 crisis type situation hidden under the surface of conventional poor NGDP performance? Given the EZ’s really sticky prices (much stickier than the U.S. and other European countries in the Great Depression), I can’t exclude that possibility. During the secondary recession period, as far as I could find, the rate of price change in each and every EZ country I looked at was greater than the rate of RGDP change. That’s astonishing.

Also, an NGDP shock is hardly a gunshot. Economies readily recover from temporary NGDP shocks. The NGDP shock is more like a not-too-hard punch in the face- hurts for quite a while, but eventually heals. The pneumonia, however, may well not heal at all.

I propose someone do a thorough study of the Great Recession in Belarus. That country never, ever has less than 10% NGDP growth.

“We know roughly how much damage big NGDP declines do to non-housing industries, and we know that they do that damage regardless of whether or not housing is also in trouble.”

-That’s still correlation, not necessarily causation, though. It doesn’t tell us if there’s a big finance-based supply-side resource allocation shock underneath the surface.

BTW, I certainly don’t deny that NGDP shocks on their own can create and exacerbate recessions. The Great Depression, for example, was pretty much all NGDP shock. Had there been no strong positive supply shock and extremely strong deflation in the early 1920s (when NGDP collapsed), things would have been very ugly.

3. December 2015 at 23:07

@Sumner – “In my view the burden of proof is on the person making the bubble claim. Either it has useful information about the ***future level of prices***, or it doesn’t.” (emphasis added)- ??? this is absurd. You cannot predict the future. Is that your metric? Then everything is flawed, including the study of history, since history rarely tells you exactly what will happen in the future. You sure have strange standards professor.

@Harding – I can’t believe you bought into the sticky wages/ money illusion thesis with NGDP / musical chairs model. There’s little evidence for this in practice. Wages may be slightly sticky but firms adjust by firing workers who are marginally productive. How does this effect the economy? Labor as a component of GDP, is that it? Then recall labor participation rates have yo-yo’d up and down over the years, are you saying we’re worse off because a few marginal employees (women, elderly, incompetents, etc) are fired? This somehow amplifies into a general recession? No sir, the reason we have recessions is due to–as the Austrians say–over-capacity in everything that has to be liquidated, Andrew Mellon style. Balance-sheet recessions due to credit card binge buying is related to this. Malinvestment. The rest is just noise.

4. December 2015 at 04:16

Would anyone be interested in a money illusion subreddit? Love the conversations and it might be a bit more legible. Just a thought. I’d be happy to set it up unless someone more “official” would want to do it.

4. December 2015 at 04:56

@Ray Lopez:”future level of prices***, or it doesn’t.” (emphasis added)- ??? this is absurd. You cannot predict the future.” Isn’t calling some an attempt of predicting the future (the bubble will burst). If not, what is it good for?

4. December 2015 at 06:29

Matt makes a simple point that Real Estate and housing prices/bubbles are local. So comparing various European nations to the US is not completely fair as Europe as a whole would be close to the US. (I suspect it would be higher than the US.) How many times did people compare the housing bubble in Spain to Florida or Ireland to Nevada, etc. Assuming the US did take a larger fall than Europe, I suspect the key differences were:

1) US companies cut employees first and asked questions later.

2) US underwater homeowners acted like corporations and cut losses earlier with more jingle mail and forcing more foreclosures.

4. December 2015 at 06:30

Krugman has been doom-mongering over Canadian home prices since at least 2011:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/04/oy-canada-2/

4. December 2015 at 06:36

Scott,

I would hardly say Dean Baker completely missed his 2002 housing price call with the 2015 inflation adjust prices. It is awfully hard to make claims out 13 years. I suspect one reason for this difference is long term mortgage rates are still 3 – 4 % while 2002 the rates were higher at 5 – 6% so monthly payments for 2015 is still likely lower than 2002.

4. December 2015 at 06:50

OT: As blogged today by Tyler Cowen at http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/12/did-unconventional-monetary-policy-give-the-economy-some-below-zero-properties.html

A PhD from UC Santa Cruz, Arsenios Skaperdas (a Baltic not Balkan name, lol; his father is also an economist), destroys Sumner’s notion that the Fed Fund rate should be negative, and that the Fed should have done more during the Great Recession. Go to the link above and read for yourself. For those of you too lazy:

Abstract: “I examine the relationship between monetary policy and growth at the zero lower bound using industry data. I devise a simple inferential test of monetary policy’s industry effects. In the absence of the zero bound, and given previous Federal Reserve behavior, the federal funds rate would have troughed in the range of -2 to -5% since 2009. If unconventional policy failed to bridge this gap, this deficit should represent a contractionary monetary shock. I create a measure of historical industry interest rate sensitivity. Estimates from this measure imply that interest rate sensitive industries, such as construction, should have suffered a 4 to 10% decrease in revenues, since 2009, in comparison to insensitive industries. I do not find that this is the case. Furthermore, differences in cross-industry revenue growth rates, ranked by interest rate sensitivity, are similar to those seen in previous economic recoveries”

Simple translation: if Sumner is right, there should have been some interest rate sensitive industries that suffered a decrease in revenues during the Great Recession more so than suffered historically. But the curious incident is that the dog did not bark. No such decrease was observed. Sumner is wrong.

4. December 2015 at 07:28

Krugman needs to stop mentioning Baker’s 2002 prediction, which I’m sure Baker would just as soon forget.

I read Dean Baker’s blog and he periodically claims that he called the bubble and that it should have been obvious to economists.

4. December 2015 at 08:08

‘I can’t believe you bought into the sticky wages/ money illusion thesis with NGDP / musical chairs model. There’s little evidence for this in practice. Wages may be slightly sticky but firms adjust by firing workers who are marginally productive. How does this effect the economy? Labor as a component of GDP, is that it? Then recall labor participation rates have yo-yo’d up and down over the years, are you saying we’re worse off because a few marginal employees (women, elderly, incompetents, etc) are fired? This somehow amplifies into a general recession? No sir, the reason we have recessions is due to–as the Austrians say–over-capacity in everything that has to be liquidated, Andrew Mellon style. Balance-sheet recessions due to credit card binge buying is related to this. Malinvestment. The rest is just noise.”

What amplifies the recession is debt deflation, which is absolutely aggravated by the laying off of marginal workers. If firms everywhere are firing ‘marginal’ employees during a time when a state of widespread over-indebtedness exists and a financial crisis has pushed investors into mass deleveraging, it means more debtors have less income to service their debts, making outstanding debts harder to pay off and causing debt service to suck up more spending that would otherwise flow into the real economy. As spending slows, prices and incomes decline further, sparking new layoffs, providing debtors with even less money to pay off their debts, making the debts harder to pay off, etc.

This is why if you plot changes in interest rates in the U.S. against changes in the level of employment you only get a loose correlation, and in some instances no correlation at all. Whereas if you graph the change in the level of (private) debt in the U.S. against changes in the level of employment, you’ll find an almost perfect correlation. (.92, to be exact)

What has happened since the recession began is hardly a validation of Austrian theories of malinvestment; it is far more a validation of Fisher and Minsky’s theories of debt deflation and financial instability.

4. December 2015 at 08:17

Scott,

Let me see if I understand your position. You think the sequence of events was:

initial shock -> Fed policy “too tight” -> nasty recession -> housing prices collapse + financial crisis

Compare to the standard narrative:

housing bubble + bank misbehavior -> housing prices collapse -> financial crisis -> Fed hits ZLB -> nasty recession

I find the latter narrative much more plausible, since it provides an explanation for the initial shock (if you accept “housing bubble” as an explanation). So in your view, where did the initial shock come from?

4. December 2015 at 08:19

Also, re: Dean Baker.

If you think there is an upward trend in fundamental housing prices, then housing prices may have been overvalued in 2002, even if they are higher now. I think that’s a plausible interpretation of the data.

4. December 2015 at 09:12

A bubble is nothing more or less than a supply or demand shock. In 1999 the demand for shares of dotcom companies greatly exceeded the supply. In 2002 the supply of shares of dotcom companies greatly exceeded the demand. That there existed such a dramatic change in the fortunes of internet companies in a short period of time is evidence of a bubble. Extreme valuations existed at the beginning or the end. Or both.

4. December 2015 at 10:11

housing bubble + bank misbehavior -> housing prices collapse -> financial crisis -> Fed hits ZLB -> nasty recession

I find [this] latter narrative much more plausible, since it provides an explanation for the initial shock (if you accept “housing bubble” as an explanation). So in your view, where did the initial shock come from?

The test of whether a narrative is convincing isn’t whether it ‘provides an explanation’, all narratives do that no matter how absurd, but whether the narrative’s explanation corresponds with the data of factual reality, such as the order in which events occur. Which makes the first narrative look a whole lot better by comparison.

As to ‘where did the initial shock came from?’, one candidate is what at the time everyone was actually screaming about, the news shows and headlines were full of, Congressional investigations were being demanded about … which was *not* the price of homes. Remember?

It was the price of oil rocketing up from $26 to $145, with a more than 100% increase in just the last 18 months through 2007 and 2008, and predictions everywhere that it was going to $200, $300…

What effect does an oil shock like that typically have on the economy? It’s truly remarkable how it has dropped so entirely out of the collective memory and “the standard narrative”.

4. December 2015 at 10:41

Expanding on my point above: the way in which the oil price shock has dropped so utterly out of the “standard narrative” of the causation of the recession, given the near hysteria about the price of oil at the time, really is impressive and deserves exploration as to an explanation.

I suggest the well known cognitive failure of ‘recency bias’.

Oil price changes hit in real time, immediately, so when the price of oil doubles rapidly people scream murder, but when it then falls by 2/3rds just as rapidly and remains low the trauma is all as quickly over, good times are back, nobody thinks about it anymore.

OTOH, when home prices fall it affects a lot of people and policies for many years to come, year-after-year, so it is always there and people keep thinking about it. It is always in mind.

So even if the latter in fact had only a small fraction of the effect on the economy as the former, it is all most people remember, so it becomes all that mattered.

4. December 2015 at 10:41

Kevin Erdmann’s blog handles the housing situation pretty well.

There is something that puzzles me to this day. There was a nearly equal run up and then fall of commercial real estate values, and then recovery of, especially in institutional quality real estate.

So if there was a bubble in housing, there was also a bubble in Class A office buildings and retail space.

But I think the best answer is that there was a reverse real estate bubble after 2008, caused by Federal Reserve Board suffocation.

Also, the entire West Coast needs to go to default highest and best use for property zoning

4. December 2015 at 11:04

Jim:

> The test of whether a narrative is convincing isn’t whether it ‘provides an explanation’, all narratives do that no matter how absurd, but whether the narrative’s explanation corresponds with the data of factual reality…

A hypothesis that explains more (i.e. is more detailed, and therefore makes more precise predictions) is preferable in general since it is easier to falsify. The hypothesis “God so willed” is trivially always in perfect accordance with the facts.

> …such as the order in which events occur. Which makes the first narrative look a whole lot better by comparison.

Didn’t housing peak in 2006, while the recession began in late 2007? That seems to favor the causality running from housing to recession over the reverse.

> As to ‘where did the initial shock came from?’, one candidate is … the price of oil rocketing up from $26 to $145, with a more than 100% increase in just the last 18 months through 2007 and 2008, and predictions everywhere that it was going to $200, $300…

The big run-up happened mainly in 2007/8, after housing peaked. And the economy didn’t do so badly over this time until the main financial crisis hit in Fall 2008. I don’t remember hearing about banks’ exposure to oil, but I heard a lot about housing.

> What effect does an oil shock like that typically have on the economy?

I would think it would be fairly small from a macro perspective. I think Jim Hamilton disagrees, though. And wouldn’t that be a negative supply shock anyway?

4. December 2015 at 11:32

The Housing Bubble/Great Recession was simply the 1980s Texas real estate bubble/S&L Crisis/regional recession except on a global scale due to the development of global capital markets.

4. December 2015 at 14:50

E. Harding, I certainly agree that Europe also has major supply side problems, but the NGDP performance has made it much worse.

Ben, Should I know what a subreddit is?

Collin, The farther out in the future, the more obvious the bubble should be.

Ray, You said:

“If Sumner is right, there should have been some interest rate sensitive industries that suffered a decrease in revenues during the Great Recession more so than suffered historically.”

Have you learned NOTHING in all the time you’ve been reading this blog? How many times do I have to tell you that monetary policy is not about interest rates?

Jonathan, You said:

“housing bubble + bank misbehavior -> housing prices collapse -> financial crisis -> Fed hits ZLB -> nasty recession

I find the latter narrative much more plausible, since it provides an explanation for the initial shock (if you accept “housing bubble” as an explanation). So in your view, where did the initial shock come from?”

Two huge problems:

1. You explanation is flat out wrong, and it’s not even debatable. The “nasty recession” occurred before rates hit zero. The decline in GDP was almost over (monthly data) by December 2008.

2. I have no problem with the idea that housing/banking distress was the “initial shock.” But shock does not imply bubble.

You said:

If you think there is an upward trend in fundamental housing prices, then housing prices may have been overvalued in 2002, even if they are higher now. I think that’s a plausible interpretation of the data.”

That’s a really weak defense of Baker. If in 2002 he had said “real housing prices might be higher by 2015”, then people would have laughed at his claim of a housing bubble in 2002. The reason these guys predict bubbles is they believe there is some normal level of real housing prices, which doesn’t change much over time, and when they rise above that they are above the level predicted by “fundamentals.”

Dan, ??????????????????????????????????????????????

Jim, Good point about oil.

Gene, Except that Texas had no bubble this time, but still had a recession. It’s all about NGDP, i.e. monetary policy.

Australia had a big housing bubble, but not big drop in NGDP. Hence no big recession.

4. December 2015 at 17:13

Australia probably didn’t have a bubble, just some really stupid housing policies. Similar with the lack of a giant bust in the UK. I’m really not sure what’s going on in Canada.

And, by the way, Scott, if you have any questions on the ancient history presented in Eric Cline’s book, ask me anything. I know a good deal about this topic.

4. December 2015 at 18:13

http://www.greenstreetadvisors.com/pdf/press/cppi/GSACPPI.pdf

Great chart on commercial property values in this release. I hope Sumner can reproduce it someday, as fodder for a post.

Commercial property value peaked in 2007 at index 100, then fell to 61.2 in 2009, and now are all the way back to 122.7.

So, if commercial real estate was a “bubble” it is now a bubble plus 20%.

But really, does not this chart make a hockey at looking at housing a something different from real estate as a whole?

4. December 2015 at 20:14

ssumner, that is because capital markets are now global and most major oil companies weren’t interested in drilling in Texas as they didn’t believe fracking could be done economically.

4. December 2015 at 23:33

@ Jonathan.

Let’s agree that a convincing narrative must correspond with reality, such as relating facts in the order that they actually occurred, and, yes, that “God so willed” shouldn’t be invoked unless one has nothing better.

Our host has replied to you “Your explanation is flat out wrong, and it’s not even debatable.”, but let’s fill this in with a little more detail. Here’s your narrative with some necessary time-line correction and factual supplements…

housing bubble + bank misbehavior -> housing prices collapse ->

financial crisis -> Fed hits ZLB -> nasty recession.The last three items are plainly out of order. The recession (dated by NBER from 12/2007) started well before the financial crisis and preceded hitting the ZLB by more. As you yourself said “the main financial crisis hit in Fall 2008.” So much for “financial crisis –> recession”.

So what *else* happened by the fall of 2008 to create a financial crisis then? As your purported cause of the housing bubble busting in 2006 seems really slow acting in having this effect, two years on and still waiting for it.

You said you preferred to deal with a hypothesis that is “more detailed”, so lets put things into correct order and add more detail, and see what one might come up with….

Housing bubble + bank misbehavior -> housing price collapse starts, 2006 -> *no* financial crisis -> massive oil price shock hits, intensifies steadily into 2008 -> recession starts, Q1 of 2008, Fed Funds rate is 4%, high above the ZLB -> still no financial crisis -> CPI deflation starts for first time since 1930s in Q3 of 2008, with Fed Funds rate at 2% still well above ZLB-> still with no fear of financial crisis, Treasury and Fed let Lehman fail, 9/15/18 -> after Lehman fails, still with no fear of financial crisis, Fed cites risk of inflation while effectively tightening money policy, 9/16/2008 (!!) -> NOW the crisis hits with fury in the financial markets -> Fed goes “yikes!” and “in response to the crisis” drops Fed Funds rate to 1.5%, still well above ZLB, 10/8/15, with stocks down 20% since 9/16….

Note well: Recession starts-> CPI deflation starts -> Fed lets Lehman fail -> Fed *increases* real FF rate by holding it at 2% amid deflation *after* Lehman fails –> financial crisis — >more time passes —> ZLB hit.

ISTM that “so God willed it”-type religious belief is needed by anyone trying to stick with your original “standard narrative” in light of that factual timeline, in my own secular opinion.

“What effect does an oil shock like that typically have on the economy?”

I would think it would be fairly small from a macro perspective. I think Jim Hamilton disagrees, though.

Yes. As do most who have considered events such as the world-wide recession coinicdent the last comparable oil shock.

And wouldn’t that be a negative supply shock anyway?

Yes, the type of supply shock that shrinks economies and contributes to recessions. And when the economy is suffering an adverse supply shock, how advisable is it for the central bank to increase the real interest rate?

I don’t remember hearing about banks’ exposure to oil, but I heard a lot about housing.

Might they be exposed to the economy? During 1930-33, 11,000 of the USA’s 25,000 banks failed, 44% of all. Was it because they were exposed to housing?

5. December 2015 at 07:04

Ben, Very interesting.

Gene, There was an enormous amount of drilling done in Texas; what difference does it make whether it’s small companies or large?

Texas has very low unemployment despite the oil bust.

5. December 2015 at 08:07

Jim:

It seems that Scott disagrees with you that the oil price increase was the main external shock, rather than housing + financial exposure to housing, so in this comment I will focus on the issue of timing of the crisis vs. real contraction vs. monetary policy.

There were two stages to the recession: pre and post-Lehman. My narrative was condensed, and mainly referred to the post-Lehman contraction. A more complete narrative would be:

phase 1: housing -> moderate financial distress / moderate real contraction / aggressive policy accommodation

phase 2: Lehman -> main financial crisis -> large real contraction / little policy accommodation (ZLB)

In the first stage, there was simultaneously some financial distress (e.g. Bear Stearns), a moderate real contraction, and *aggressive* policy accommodation, as the Fed lowered the FFR from 5% to 2% (60% of the way to the ZLB!). I don’t think there was much financial amplification in this stage.

After Lehman, the main part of the financial crisis occurred, with falling stock prices, bank failures and bailouts, liquidity crises, etc. The main part of the real contraction happened in this period, likely due to the financial crisis.

Now to the heart of our disagreement: monetary policy. The big picture is that the Fed lowered the FFR from 5.25% to 3% before Lehman. Then (yes) up by 25bp in mid September, before rapidly falling through the rest of the Fall: 1.5% by the end of September, under 1% by the end of October, before officially hitting the ZLB in early December.

Overall, that’s a picture of aggressive policy accommodation, from 5% to 0% in a bit over a year. Clearly the Fed decision on 9/16/2008 was a mistake, but in light of the overall large accommodation provided, it seems a bit strange to highlight one upward jot as the cause of the main part of the contraction, rather than fallout from the failure of Lehman.

Importantly, although interest rates didn’t hit zero until December, the ZLB was still a constraint on policy throughout the Fall. Because people knew that the Fed couldn’t cut rates much more, they expected less policy accommodation, which raised long rates and lowered growth expectations. Hypothetically, if the FFR had been 5% in September 2008 the Fed would have cut by much more than 2% over the next several months, and this expectation would have stabilized demand quite a bit.

5. December 2015 at 09:19

ssumner, you have your chronology all wrong and you are totally missing my point…stop talking about Texas during the Housing Boom because my point has almost nothing to do with that!! Fracking was not really proven economical until around 2008 so that was after the Bubble, and it started with natural gas and the reason Texas recovered from the Great Recession quickly was because fracking for oil was proven economical around 2010.

My point is that the Housing Boom/Great Recession was very similar to the early 1980s Texas real estate boom/S&L Crisis/regional recession. So the conditions of both periods were similar with the big difference being at some point capital markets developed into GLOBAL markets. So the conditions were high oil prices combined with a lack of investment in oil production and then the capital from oil profits wreaks havoc in the economy. In the 1980s that capital wreaked havoc at a regional level and in the 2000s it wreaked havoc on a global level. Bernanke’s Global Saving Glut is a similar theory but China plays a bigger role than ME oil producers.

5. December 2015 at 09:54

Paul Krugman: “Economics: What Went Right”

http://equitablegrowth.org/must-read-paul-krugman-economics-what-went-right-2

5. December 2015 at 11:12

Mario Draghi on Friday: “We have the power to act. We have the determination to act. We have the commitment to act.”

http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/04/investing/mario-draghi-stock-market

http://www.nasdaq.com/article/a-fireside-chat-with-mario-draghi-20151204-00681

5. December 2015 at 13:24

Scott and/or Nick Rowe if you’re still reading:

I’m not trolling, I’m sincerely asking. What do you think house prices should do, if nobody made any obvious mistakes? Just rise with CPI so that the expected appreciation in real housing prices is 0% for any time horizon, at the moment of purchase?

5. December 2015 at 20:00

Bob, I think the problem is people view the Housing Bubble as the problem with the 2000s economy whereas is reality it was a symptom of a dysfunctional economy. The major reason the economy was dysfunctional was because of an energy crisis due to unprecedented Chinese growth.

So capital searches for yield and the obvious place for profits made from oil to go would be more production…but that didn’t happen in the 2000s for a myriad of reasons. So the problem with an energy crisis is that the smart investors will sit on the sidelines due to the importance of energy to the global economy. So the most common types of investments the 2000s were things like real estate and franchises.

So now Miami is experiencing a real estate boom but it is not credit driven and so it is not the symptom of underlying dysfunction…at least with the US economy.

5. December 2015 at 20:57

Bob, what you described basically describes the 3/4 of the country where high skilled workers weren’t bidding up rents to access high income labor markets where housing supply is severely constrained by local politics. That’s more or less how housing markets work even when lots of people “make mistakes”.

6. December 2015 at 03:18

Bob: “What do you think house prices should do, if nobody made any obvious mistakes? Just rise with CPI so that the expected appreciation in real housing prices is 0% for any time horizon, at the moment of purchase?”

Definitely not. Even under perfect foresight, and with quality-adjusted house prices, that wouldn’t happen. House prices should reflect Present Value of future rents, and rents should vary over time in accordance with standard supply and demand stuff, and the rate of interest at which that PV is calculated varies over time too.

In the very long run, my gut says there will be a small upward trend in real house prices, because it’s hard to use technology to replicate desirable locations (land), for which people pay more as we get richer. The rate of technical progress in housing is less than in most goods. I lived in a 500 year old house as a kid. I first learned economics in an 700(?) year old building. I would never use a 500 year old car or computer.

6. December 2015 at 10:51

I agree with Nick. There are some things that can create deviations from a flat real trend. It is useful to think about several factors, rent & home prices, both real and nominal, and both in absolute terms and relative to incomes. For instance those long term subtle supply constraints might raise rents and prices on single properties without changing housing expenses as a proportion of income. Falling real long term interest rates, on the other hand, might raise home prices and real housing expenditures but not rent on existing homes or as a proportion of incomes.

6. December 2015 at 10:59

Jonathan, I think the oil shock was also important. Both shocks pushed monetary policy off course. Neither had a strong direct effect on the economy.

Gene, You said:

“Fracking was not really proven economical until around 2008 so that was after the Bubble, and it started with natural gas and the reason Texas recovered from the Great Recession quickly was because fracking for oil was proven economical around 2010.”

I don’t agree:

1. The growth rate of Texas population slowed after fracking began.

2. Texas unemployment stayed very low during the fracking bust.

I don’t agree with your second paragraph, the Great Recession was caused by tight money. Unemployment stayed low during January 2006 to April 2008, even as housing construction fell in half. It was monetary policy that caused the Great Recession.

Thanks Travis.

Bob, If people had perfect foresight then housing prices would be fairly stable. Of course they would not be precisely stable, but they would probably change very gradually in real terms. If people make mistakes that don’t violate Ratex, then of course housing price could be very unstable–it depends on the nature of the shocks hitting the system.

6. December 2015 at 11:32

ssumner, once again my point doesn’t really have anything to do with fracking because we are discussing the period of time BEFORE 2008.

I think Bernanke’s GSG is the best theory out there with my only issue with it is that he downplays the global oil market’s impact on the global economy. The context of the 2000s was that during the 2000 election oil prices were an issue and 9/11 and the early 2000s recession merely delayed the drastic increase in oil demand everyone was predicting in 2000. For a myriad of reason supply never increased and many believed we were going to be forced to import LNG! The smart money was very nervous in the 2000s because only a few people in Houston saw a way out of the energy crisis.

Heck, just go back and read articles about Detroit’s reliance on SUVs from the early 2000s to see the mess we were headed for.

10. December 2015 at 23:43

This article is a bit amusing, Scott. I was in Reno, NV in 2005 and I talked to many RE agents who were alarmed that inventories of homes had gone up from 500 to 3000 homes on the market at one time. I have no idea why people stopped buying, but they obviously stopped buying. Prices were astounding for small, old houses. The wages did not justify the prices. I don’t know if banks stopped lending or demand dried up or both. But the houses on the market grew into an enormous inventory. And then the crash came, Scott. You don’t believe in bubbles but it was a bubble. The fact that you don’t think this was a bubble is disturbing to me.

10. December 2015 at 23:47

So, if you don’t think Reno, NV in 2005 was a bubble, you certainly must feel comfortable with Sweden having 70 percent of borrowers doing interest only loans. And you must be opposed to the government wanting these people to pay down their principle because it could cause people to walk away from homes. The only thing Sweden has going for it that Reno didn’t is control of housing being produced so inventory does not get too high. But fear could enter that market anyway right? I recall that Japanese real estate crashed and there was not an out of control inventory. I think I read that somewhere.

11. December 2015 at 08:46

Gary, I was certainly not “comfortable” with our financial system in 2005, I was highly critical of the system.

11. December 2015 at 09:04

@Gary Ajnderson: “I have no idea why people stopped buying … You don’t believe in bubbles but it was a bubble.”

Your own comment seems self-contradictory. You already know that you don’t understand what happened, but that doesn’t stop you from drawing an (unsupported) overconfident conclusion anyway.

“The wages did not justify the prices.”

Wages and prices are nominal quantities, right? And current house prices are “justified” by future (nominal!) rents and prices, right? So surely the future price level matters, at least a little bit, in this analysis, does it not?

11. December 2015 at 09:15

Yes Don, there is always an element of speculation in real estate. So betting on the future does drive prices. But now we know prices don’t always go up, so there is a greater element of risk.

3. January 2016 at 23:14

[…] The inevitability (or illusion) of history — real estate bubble edition. […]