Let’s go back to March 3, 2009. Here’s Paul Krugman:

As Brad DeLong says, sigh. Greg Mankiw challenges the administration’s prediction of relatively fast growth a few years from now on the basis that real GDP may have a unit root — that is, there’s no tendency for bad years to be offset by good years later.

I always thought the unit root thing involved a bit of deliberate obtuseness — it involved pretending that you didn’t know the difference between, say, low GDP growth due to a productivity slowdown like the one that happened from 1973 to 1995, on one side, and low GDP growth due to a severe recession. For one thing is very clear: variables that measure the use of resources, like unemployment or capacity utilization, do NOT have unit roots: when unemployment is high, it tends to fall. And together with Okun’s law, this says that yes, it is right to expect high growth in future if the economy is depressed now.

But to invoke the unit root thing to disparage growth forecasts now involves more than a bit of deliberate obtuseness.

And here is Greg Mankiw’s reply:

Paul Krugman suggests that my skepticism about the administration’s growth forecast over the next few years is somehow “evil.” Well, Paul, if you are so confident in this forecast, would you like to place a wager on it and take advantage of my wickedness?

Team Obama says that real GDP in 2013 will be 15.6 percent above real GDP in 2008. (That number comes from compounding their predicted growth rates for these five years.) So, Paul, are you willing to wager that the economy will meet or exceed this benchmark?

And here’s what I wrote, 5 years later:

Krugman wisely decided to avoid this bet, which suggests he’s smarter than he appears when he is at his most political. In any case, the actual 5 year RGDP growth just came in at slightly under 6.3%. That’s not even close. Mankiw won by a landslide.

In January 2011, Tyler Cowen wrote a book entitled “The Great Stagnation.” So far Tyler’s hypothesis has proven correct. (Oddly, the media often refer to Larry Summer’s stagnation hypothesis, which (AFAIK) came much later.)

In 2013 Tyler made a bet with Bryan Caplan, that unemployment would not fall quickly back to 5%:

Tyler just bet me at 10:1 that U.S. unemployment will never fall below 5% during the next twenty years. If the rate falls below 5% before September 1, 2033, he immediately owes me $10. Otherwise, I owe him $1 on September 1, 2033.

Readers of my blog know that I would have agreed with Bryan. Tyler Cowen responded by pointing to reasons why these bets are not a good idea:

Bryan Caplan is pleased that he has won his bet with me, about whether unemployment will fall under five percent. I readily admit a mistake in stressing unemployment figures at the expense of other labor market indicators; in essence I didn’t listen enough to the Krugman of 2012. This shows there were features of the problem I did not understand and indeed still do not understand. I am surprised that we have such an unusual mix of recovery in some labor market variables but not others. The Benthamite side of me will pay Bryan gladly, as I don’t think I’ve ever had a ten dollar expenditure of mine produce such a boost in the utility of another person.

That said, I think this episode is a good example of what is wrong with betting on ideas. Betting tends to lock people into positions, gets them rooting for one outcome over another, it makes the denouement of the bet about the relative status of the people in question, and it produces a celebratory mindset in the victor. That lowers the quality of dialogue and also introspection, just as political campaigns lower the quality of various ideas — too much emphasis on the candidates and the competition. Bryan, in his post, reaffirms his core intuition that labor markets usually return to normal pretty quickly, at least in the United States. But if you scrutinize the above diagram, as well as the lackluster wage data, that is exactly the premise he should be questioning.

As I’m the only one in this exchange fessing up to what I got wrong, and what I still don’t understand, and what the complexities are, in a funny way…I feel I’m the one who won the bet.

I agree with Tyler’s skepticism regarding the utility of public bets; they oversimplify a very complex set of issues. They also subtly imply that greatness is a function of not being “wrong” about particular questions. I’d argue that one doesn’t become a truly great scientist until one’s views have been partially discredited. That means people are taking your ideas seriously, and pushing them to the point where they are no longer intellectually progressive. (Think Copernicus, Newton, Einstein, Darwin, etc.)

However, as someone who agreed with Caplan, I don’t entirely accept the implication of Tyler’s final sentence. I can’t speak for Bryan, but here are the views I’ve expressed:

1. Cycles in unemployment are largely caused by nominal wage stickiness, and unemployment will usually revert back to the natural rate, which tends to be fairly stable in the US (but not completely stable).

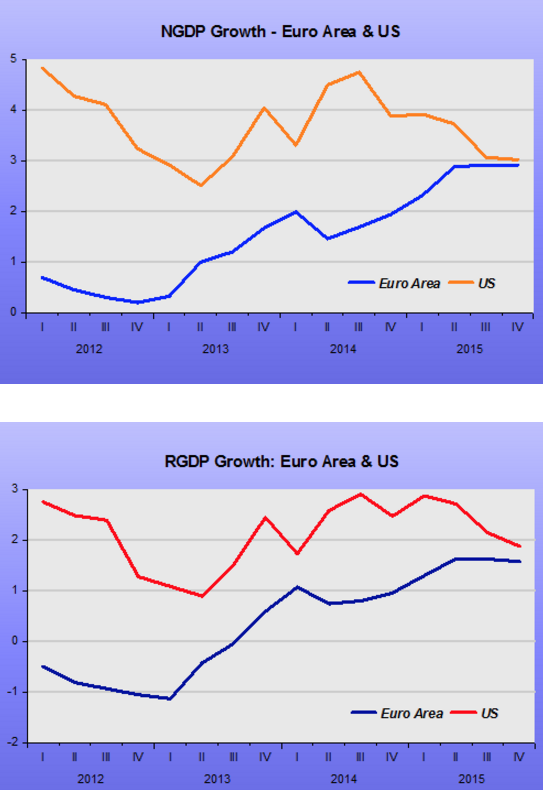

2. The US is entering a Great Stagnation, where 3% NGDP growth will be the new norm, measured RGDP growth will also slow sharply, but of course it’s not clear what RGDP actually is, because it’s not clear what economists mean by the term “price level.”

3. The Labor Force participation rate has historically been unstable, unlike the natural rate of unemployment, responding to demographics, welfare reform, disability insurance, prison incarceration, etc., etc., etc.) Wage stickiness doesn’t explain this. But Tyler was also skeptical of how far Bryan and I pushed the wage stickiness concept. Since our view is that wage stickiness explains changes in the unemployment rate, but not the LFPR, Bryan winning his bet is at least as small point in favor of the sticky wage model.

4. Fiscal austerity would not slow growth in 2013, a claim Paul Krugman contested. I was right and Krugman was wrong.

5. Repealing the extended unemployment benefits in early 2014 should have modestly increased new job creation, by boosting the supply of labor. This would be true even if NGDP growth (i.e. AD) did not accelerate. Paul Krugman also contested this claim. Again, I was right. Job growth in 2014 was substantially above the 2010-13 rate, despite very modest growth in NGDP. Of course Krugman has been right about many things, especially when he agreed with market monetarists. Thus he has criticized the mainstream conservative prediction that “easy money” would lead to high inflation.

6. I’ve consistently predicted that unemployment would fall faster than the Fed thought, and that NGDP growth and inflation would be less than the Fed thought. That’s actually sort of threading the needle, as faster falling unemployment would normally be associated with faster than normal NGDP growth.

Despite the fact that I’ve recently ended up being right more often than wrong, I think the importance of specific predictions is overrated. If I had been blogging in 2006-09 I would have been wrong about lots of things, because the market was wrong about lots of things. The economy is very hard to predict, and hence I’ve been lucky. More important is the reasoning process used. Here is how I’ve approached this:

1. For low NGDP growth and inflation predictions I’ve relied on market forecasts, which generally seemed more bearish than Fed forecasts.

2. For the Great Stagnation, early on I noticed a “job-filled non-recovery”, which many people oddly called a jobless recovery. The unemployment rate fell sharply despite anemic RGDP and NGDP growth (for a recovery period). So I reasoned that if RGDP growth was only 2.0% to 2.5% during a period of fast falling unemployment, then the trend rate of growth must be really slow. So far I’ve been correct (and I hope my prediction is soon refuted, for the sake of the economy.)

3. For the unemployment compensation issue I relied on basic theory, and on previous studies of the effect of UI on jobless rates. Back in 2008, Brad DeLong predicted higher unemployment as a result of a very small increase in benefits under President Bush. It seemed to me that people like Krugman were abandoning mainstream economics for ideological reasons.

4. Standard theory, pre-2008, also implied that the monetary authority drove AD, and that fiscal policy would only impact growth by shifting the AS curve. I saw no reason to abandon the standard view.

5. As far as wage stickiness and unemployment, my views were shaped by many factors, including my study of the Great Depression, and the fact of wage stickiness documented by many studies. I also relied upon the strong theoretical implication that if nominal wages are sticky then nominal GDP shocks will lead to volatility in hours worked. As far as the unemployment rate recovery predicted by Caplan, I relied on both theory (Friedman/Phelps) and evidence—the fact that the US natural rate seems fairly stable at around 5%. That’s the best I could do, and in this case I was right. But if I’d lived in Western Europe in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I would have been wrong and Tyler would have been right, as the unemployment rate jumped sharply, and never went back down (except in a few countries like Germany, and even then only much, much later.)

Market forecasts are the best we can do. I suggest that readers pay less attention to who predicted what, and more on the reasoning process behind their predictions. Occasionally people will get lucky and nail a prediction that the markets missed (think Roubini, John Paulson, Shiller, etc.) But when you look at their overall track record it’s clear that luck was involved; no one can consistently predict the macroeconomy. Nor should we focus on who has the most impressive mathematical model. Instead we should focus on who has a coherent explanation for what is occurring, an explanation that is consistent with well established theory, and that can be applied to a wide range of cases. I hope market monetarism is one of those coherent explanations.

PS. I just returned from the Warwick Economics Summit, and was very impressed by the Warwick students. I would especially like to thank Ibraheem Kasujee, who helped arrange the visit. It was good to get out of the Puritan States of America for a few days, and attend a student ball where drinks are served to 18 year olds. At Bentley even the faculty can’t drink a glass of wine at the Holiday Party. And Bentley just banned smoking everywhere—basically telling the smokers (who used to huddle outside in the cold) to go away, we don’t want you here. This university is only for PC puritan paternalists. (On the plus side, our students do get good jobs.)

I had planned on being home for dinner on Monday, but instead (due to snow at the Boston airport) I was 30 miles north of Reykjavik (at 11 pm Iceland time), in the middle of nowhere, standing in a cold wind with no hat on, looking straight up at a zillion stars in the sky–and a few northern lights as well. But now I’m back and have a huge amount of catching up to do. (Here’s my earlier unexpected layover in Iceland.)

For readers who didn’t get their fill of Krugman bashing here, I also have a new Econlog post.