Krugman on high stock prices

Paul Krugman has an excellent post discussing why stock prices are relatively high. Apart from the opening paragraph, where he (implicitly) dismisses the EMH and rational expectations, I almost entirely agree with his interpretation. (OK, the last bit defending Obama is also a bit questionable.) I have expressed similar views, although of course Krugman expresses his ideas in a much more elegant fashion. David Glasner was critical of this observation by Krugman:

But why are long-term interest rates so low? As I argued in my last column, the answer is basically weakness in investment spending, despite low short-term interest rates, which suggests that those rates will have to stay low for a long time.

Here’s how David responded:

Again, this seems inexactly worded. Weakness in investment spending is a symptom not a cause, so we are back to where we started from. At the margin, there are no attractive investment opportunities.

First let’s be clear about what Krugman means by “investment spending” in the quote above. He clearly does not mean the dollar volume of investment spending, in equilibrium, because equilibrium quantities cannot “cause” anything, including low interest rates. Instead he means the investment schedule has shifted to the left, and that this decline in the investment schedule (on a savings/investment diagram) has caused the lower interest rates. And that seems correct.

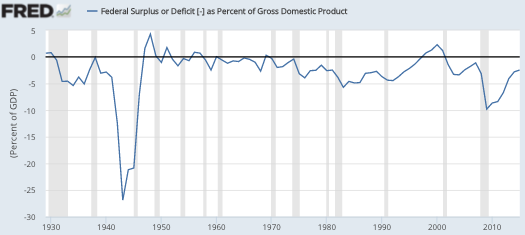

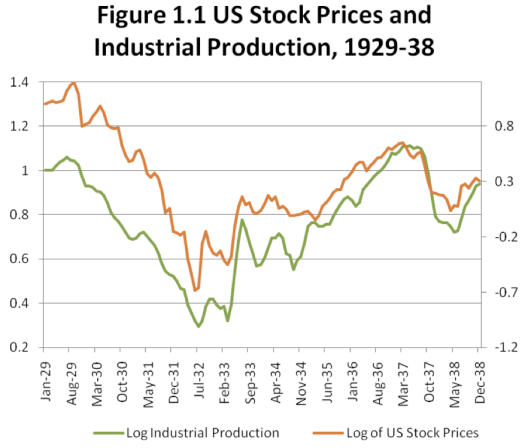

Unfortunately, Krugman adds the phrase “despite low short-term interest rates”, which only serves to confuse things. Changes in interest rates have no impact on the investment schedule. There is nothing at all surprising about low investment during a time of low interest rates, that’s normally the relationship we see. (Recall 1932, 1938, and 2009).

David is certainly right that Krugman’s statement is “inexactly worded”, but I’m also a bit confused by his criticism. Certainly “weakness in investment spending” is not a “symptom” of low interest rates, which is how his comment reads in context. Rather I think David meant that the shift in the investment schedule is a symptom of a low level of AD, which is a very reasonable argument, and one he develops later in the post. But that’s just a quibble about wording. More substantively, I’m persuaded by Krugman’s argument that weak investment is about more than just AD; the modern information economy (with, I would add, a slow growing working age population) just doesn’t generate as much investment spending as before, even at full employment.

I’d also like to respond to David’s criticism of the EMH:

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) is at best misleading in positing that market prices are determined by solid fundamentals. What does it mean for fundamentals to be solid? It means that the fundamentals remain what they are independent of what people think they are. But if fundamentals themselves depend on opinions, the idea that values are determined by fundamentals is a snare and a delusion.

I don’t think it’s correct to say the EMH is based on “solid fundamentals”. Rather, AFAIK, the EMH says that asset prices are based on rational expectations of future fundamentals, what David calls “opinions”. Thus when David tries to replace the EMH view of fundamentals with something more reasonable, he ends up with the actual EMH, as envisioned by people like Eugene Fama. Or am I missing something?

In fairness, David also rejects rational expectations, so he would not accept even my version of the EMH, but I think he’s too quick to dismiss the EMH as being obviously wrong. Lots of people who are much smarter than me believe in the EMH, and if there was an obvious flaw I think it would have been discovered by now.

David concludes his post as follows:

Thus, an increasing share of total investment has become capital-deepening and a declining share capital-widening. But for the economy as a whole, this self-fulfilling pessimism implies that total investment declines. The question is whether monetary (or fiscal) policy could now do anything to increase expectations of future demand sufficiently to induce an self-fulfilling increase in optimism and in capital-widening investment.

I would add that the answer to the question that David poses is clearly “yes”, as the Zimbabweans have so clearly demonstrated. I would rather avoid terms like “self-fulfilling pessimism”, as AD depends on monetary policy, or combined monetary/fiscal policy is you are a Keynesian. Either way it don’t think it’s useful to view AD as depending on the expectations of investors, pessimistic or not. Those expectations merely respond to what the policymakers are doing, or not doing, with NGDP.

PS. Yes, I do understand that under certain monetary policy stances, such as a money supply or interest rate peg, exogenous expectations impact AD. I just don’t think it’s useful to view those pegs as a baseline policy.

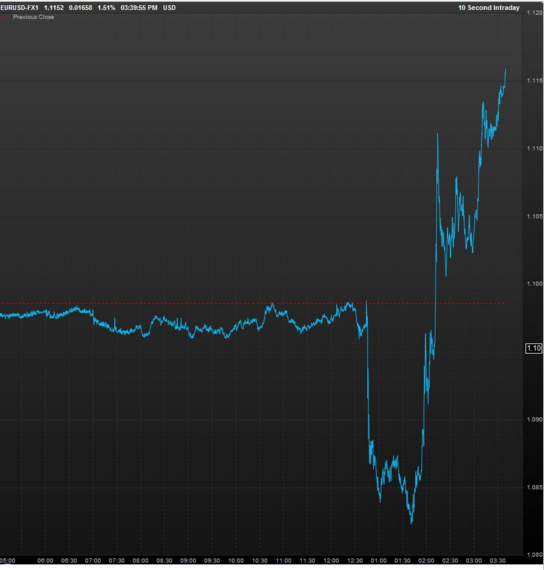

PPS. Let me repeat what I said earlier, we are going to have an interesting test of the impact of uncertainty on (British) GDP, over the next few months. Not a definitive test (which would require observations with and without NGDP targeting, to tease out AD vs. AS channels), but certainly a suggestive test. I have an open mind at this point, and am eager to learn.