Print the legend

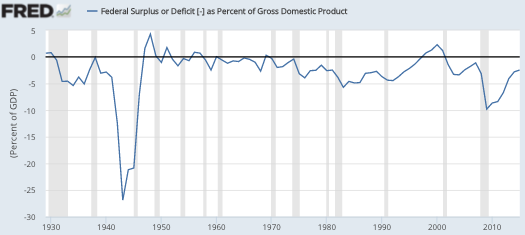

As I get older, I become increasingly interested in the mythological folktales that are believed by most economists. For instance the idea that LBJ refused to pay for his guns and butter program, ran big deficits, and kicked off the Great Inflation. All you need to do is spend 2 minutes checking deficit data on FRED to know that this is a complete myth, but apparently most economists just can’t be bothered.

During the 1960s, the budget deficit exceeded 1.2% of GDP only once, in fiscal 1968 (mid-1967 to mid-1968. LBJ responded with sharp tax increases in 1968, and the deficit immediately went away.

During the 1960s, the budget deficit exceeded 1.2% of GDP only once, in fiscal 1968 (mid-1967 to mid-1968. LBJ responded with sharp tax increases in 1968, and the deficit immediately went away.

The LBJ guns, butter and deficits story is too good to drop now, it’s in all the textbooks. It would be like admitting that the textbooks were wrong when they tell students that the classical economists believed that money was neutral and that wages and prices were flexible. We can’t do that, it’s too confusing.

Another one I love is that monetary policy impacts the economy with “long and variable lags”.

I’ve talked about this before, but today I have a bit more evidence. The idea that monetary policy affects RGDP with long and variable lags has three components, one or more of which must be true for the theory to hold:

1. Monetary policy affects NGDP expectations with a long and variable lag.

2. Changes in NGDP expectations affect actual NGDP with a long and variable lag.

3. Changes in actual NGDP affect actual RGDP with a long and variable lag.

All three are false. The third claim is obviously false; NGDP and RGDP tend to move together over the business cycle. So the entire theory of long and variable lags boils down to the relationship between monetary policy and NGDP.

The first claim is also obviously false, as it would imply a gross failure of the EMH. Now the EMH is clearly not precisely true, but it’s also obvious that market expectations respond immediately to important news events. Even EMH critics like Robert Shiller don’t claim that an earnings shock hits stocks two week later; it hits stock prices within milliseconds of the announcement. That part of the EMH is rock solid. There is no lag between policy shocks and changes in expectations of future NGDP growth.

So the entire long and variable lags theory rests on the second claim, that NGDP responds with a lag to changes in future expected NGDP. Unlike the first and third claim, that’s possible. But it’s also highly, highly unlikely. While we don’t have an NGDP futures market, the markets we do have strongly suggest that markets (and hence expectations) move with the business cycle, not ahead of the cycle.

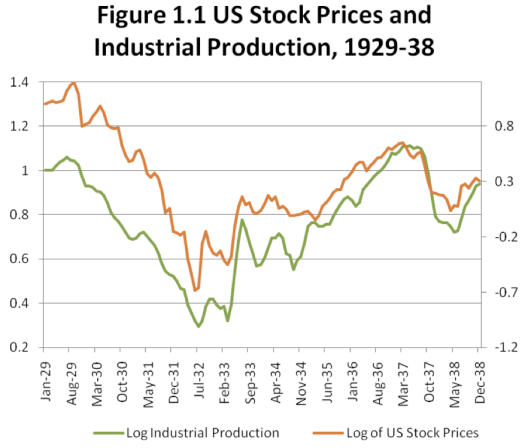

Perhaps the best period to test this theory is the 1930s. That decade saw massive RGDP and NGDP instability, which was clearly linked to asset price changes. Put simply, the Great Depression devastated the stock market. Here’s the correlation between stock prices and industrial production, from my new book:

The stock market is clearly not a leading or lagging indicator; it’s a coincident indicator. And that’s not just true in the 1930s; it’s also true today:

The stock market is clearly not a leading or lagging indicator; it’s a coincident indicator. And that’s not just true in the 1930s; it’s also true today:

The onset of the recession lines up, as does the steep part of the recession. The stock recovery in 2009 did lead by a few months, but the recent slump in IP led stocks by a few months. In any case, there are no long and variable lags; it’s basically a roughly coincident indicator when there are massive changes in NGDP.

The onset of the recession lines up, as does the steep part of the recession. The stock recovery in 2009 did lead by a few months, but the recent slump in IP led stocks by a few months. In any case, there are no long and variable lags; it’s basically a roughly coincident indicator when there are massive changes in NGDP.

If there actually were long and variable lags between changes in expected NGDP and changes in actual NGDP (and RGDP), then forecasters would be able to at least occasionally forecast the business cycle. But they cannot. A recent study showed that the IMF failed to predict 220 of the past 220 periods of negative growth in its members. That sounds horrible, but in a strange way it’s sort of reassuring.

Suppose that the business cycle is random, unforecastable, as I claim. And suppose that declines in GDP occurred one out of every five years, on average. In that case, the rational forecast would always be growth. As an analogy, if I were asked to forecast a “green outcome” in roulette, I never would. Each spin of the wheel I’d forecast red or black. I’d end up forecasting 220 consecutive “non-greens” outcomes. And yet, there would probably end up being about 11 or 12 green outcomes during that period, and I’d miss them all. A 100% failure to predict greens. Because I’m smart.

Of course if there really were long and variable lags, say 6 to 18 months, then there would be occasions where the IMF would notice extremely contractionary monetary policy, and accurately predict recessions a year later. I’m not saying they’d always be accurate. The lags are “variable” (a cop-out to cover up the dirty little secret that there are no lags, just as astrologers cover their failures with the excuse that their model is complicated, and doesn’t always work.) No, they would not always be successful, but they’d nail at least some of those 220 recessions. But they predicted none of them. And that’s because there are no lags. Because recessions begin immediately after the thing that causes recessions happens.

That’s the message the markets are sending loud and clear. But economists can’t be bothered; they have their comforting stories. Who can forget this line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance:

Ranson Stoddard: You’re not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?

Maxwell Scott: No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

Tags:

4. May 2016 at 07:49

Then why did the Great Inflation occur?:

1) Monetary policy was in denial (like the Republican Party on Trump in January) about the 1970s and always two steps behind.

2) The economy was overheating from too many jobs created without lower wages.

3) Not enough supply side economics until Carter and Reagan changed that. (And let us give our props to Carter.)

Of course for today, it feels like the Fed is a step behind the deflation, and our job market is on the other side of the demographic 1970s boom.

4. May 2016 at 07:57

Collin, Simple, the Fed printed lots of base money. If you do that when interest rates are rising (and they were rising in the 1960s) you get more M and more V, a recipe for inflation.

Supply-side issues had little or nothing to do with the Great Inflation. Another myth, as RGDP growth averaged about 3% during the 1970s.

4. May 2016 at 08:00

ssumner writes:

Close but not quite. The short reaction time you describe is correct for news the market is expecting (as in “has advance notice of”, which applies for things like embargoed news and data releases) or where automated trading programs have been programmed in advance to respond to certain unknown events if they should ever be mentioned in the news, which they will respond to within milliseconds of the appearance of a news story (this is not a real example, but think of things like the close proximity combination of the phrases “missile attack” and “oil field” in a news story, which might prompt an automated system to execute a very different set of trades compared to what it was doing before such news might break).

The story is a different where genuinely unknown events occur, where human intervention is required to establish a trading strategy in response to an event. Here, the initial reactions will take place typically within a 2 to 4 minute window of the occurrence of the market-driving news event.

We’ve actually seen both scenarios play out in the case of a news story that turned out to be false, where the automated systems responded very quickly, but as it was reviewed by human intelligence and its content was determined to not be valid, the correction response took place two to four minutes after the initial news broke. People fighting the machine!

But then, that’s just what happens for an initial response to new information. Not every system and person learns of an event at the same time or responds to it in the form of executable trades so instantly. We have also seen retreads of stories treated like initial news events, driving new market responses hours after the actual news being first reported.

So if you like, the strongest portion of the EMH, that markets respond quickly to new information, holds for an initial response to market-driving news events, after which it the response becomes less efficient and more noisy. There is more friction in the systems of markets than the stronger versions of the EMH indicates.

4. May 2016 at 08:05

You must not just look at the deficit, but the unemployment rate as well. The deficit during the Vietnam and Korean wars was especially high for the rates of unemployment existing at the time:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=14Kr

Still doesn’t explain the Great Inflation, though, which was caused by the Fed continuing to allow high NGDP growth (especially after 1975), while real growth slowed dramatically.

Also, if you look closely at your stock market chart, there is a lag of about 2-3 months between the S&P and Industrial Production Index.

“In any case, there are no long and variable lags; it’s basically a roughly coincident indicator when there are massive changes in NGDP.”

-Depends what you mean by “long”.

“Because I’m smart.”

-But if you had no prior preconceptions as to whether recessions were random or not, you’d trust the more accurate forecaster. And that wouldn’t necessarily be you.

“Because recessions begin immediately after the thing that causes recessions happens.”

-I’m reminded of your discussion of causation in your book. Correlation is more useful here.

4. May 2016 at 08:27

“to allow high NGDP growth (especially after 1975), while real growth slowed dramatically.”

-I meant both of these less labor force growth, BTW.

4. May 2016 at 08:35

Print the Legend movie clip from john Ford’s, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=363ZAmQEA84

4. May 2016 at 09:10

Great post. Great movie too even if John Wayne and James Stewart looked a little old to be sparking for young love…

And who remembers any more that the Cato Institute called Ronald Reagan the greatest protectionist since Herbert Hoover? Or that Milton Friedman said Reagan made Smoot-Hawley look benign?

Still…those were the days….

4. May 2016 at 10:26

Ironman, Good point, of course 2 to 4 minutes is not long and variable.

Harding, You said:

The deficit during the Vietnam and Korean wars was especially high for the rates of unemployment existing at the time”

if you are going down that road, I could come up with lots of counterarguments. In real terms the US government ran surpluses during Vietnam. Aren’t real variables superior to nominal variables? Is that what the text books teach us.

The standard model of government debt (Barro, 1979?) says government should run bog deficits during wartime, and pay them off during peacetime. LBJ ran smaller deficits than the model calls for.

I could go on and on. The point is that it’s a myth that LBJ ran big deficits.

I don’t see the lag you point to, but even if you were right it would be very short.

Thanks Richard.

4. May 2016 at 10:43

Does a change in NGDP expectation cause a change in NGDP, or does a change in NGDP cause a change in NGDP expectations?

I would say that there is more of the latter than the former. Indeed sometimes an action such as easier money from the Fed may boost NGDP expectations. But for the most part, NGDP expectations seem to be a reaction to current levels of growth. And since we don’t get a good GDP print but with a 4 month lag. At times, NGDP expectations might be a reaction to historical levels of output.

4. May 2016 at 10:52

Regarding the 60’s inflation, I thought that the Fed actually believed that Phillips curve nonsense, that they could “trade” inflation for unemployment.

Turned out that they couldn’t and they got both inflation and unemployment in return.

And why do econ text books continue to publish that Phillips curve myth? Talk about mythological folktales! Not only is it a myth, it is a potentially dangerous myth.

4. May 2016 at 11:02

“Regarding the 60’s inflation, I thought that the Fed actually believed that Phillips curve nonsense, that they could “trade” inflation for unemployment.”

-That wasn’t really true, instead, it was the myth of Federal Reserve impotence.

ssumner, as a rule, when the unemployment rate drops, so does the Federal deficit. If the U.S. is running tiny surpluses while the unemployment rate is below 4%, that means it would be running a pretty huge deficit if the unemployment rate was normal. That’s what the graph I linked to shows.

LBJ ran pretty large unemployment-adjusted deficits, peaking in 1967. And the unemployment-adjusted deficit is soaring to above Bush-era levels today. So sad the gridlock in Congress is over.

Perhaps a Keynesian could argue a large unemployment-adjusted deficit overheats the economy with AD.

4. May 2016 at 12:43

If you want the triumph of stories over truth, try development economics. (Still reading Lord Bauer’s collection: amazing amount of alleged analysis and commentary seems to have been fact free, or fact contradicted.)

4. May 2016 at 15:07

Your “long and variable lags” argument puzzles me, Scott. I had always understood Friedman’s claim to be that changes in M effect both NGDP and RGDP relatively quickly; it is P, in contrast, that responds with a “long and variable” lag. Is this false?

4. May 2016 at 15:16

“Throughout this campaign, I said the Lord may have another purpose for me,” Kasich said. “As I suspend my campaign today, I have renewed faith, deeper faith, that the Lord will show me the way forward and purpose for my life.”

I guess the Lord does not want Kasich building more aircraft carrier strike forces.

There are legends, then there are urban legends, and then there are present-day legends.

For some reason, Kasich was not regarded as a lunatic. Citing divine guidance is normal in the GOP.

4. May 2016 at 16:06

This analysis is poor. The metric of deficit as a percent of GDP is a poor metric because government spending adds to GDP virtually dollar for dollar, when the Fed prints money to finance the deficits, which is what occurred during that period.

There is no reason why deficits as a percent of GDP has to increase before the theory that “LBJ did not pay for his guns and butter” is true. LBJ ran big deficits, and GDP rose along with it.

————————-

“Another one I love is that monetary policy impacts the economy with “long and variable lags”.

I’ve talked about this before, but today I have a bit more evidence. The idea that monetary policy affects RGDP with long and variable lags has three components, one or more of which must be true for the theory to hold:

1. Monetary policy affects NGDP expectations with a long and variable lag.

2. Changes in NGDP expectations affect actual NGDP with a long and variable lag.

3. Changes in actual NGDP affect actual RGDP with a long and variable lag.”

“The third claim is obviously false; NGDP and RGDP tend to move together over the business cycle.”

REPEAT AFTER ME: MONETARY POLICY IS NOT CHANGES IN NGDP.

Talk about equivocation! When people say that monetary policy has long and variable lags on the economy, they are not defining monetary policy in terms of NGDP. To then define monetary policy in terms of NGDP and then disproving the “long and variable lags” theory is to mischaracterize the theory.

The quantity of money that the Fed creates put of thin air, THAT is what has long and variable lags, because it takes time for the additional money to go from the banks, to borrowers, to factor owners, to other factor owners, and so on, person to person, which then people take time to adjust prices, and choose investment projects, which then influences the production structure of the economy, which then affects prices more, all scientifically unpredictable.

Your critique of the long and variable lags theory does not even address the long and variable lags theory. Not everyone, and certainly not the discoverers of the theory, had NGDP in mind as monetary policy. You are engaging in a psychological projection.

4. May 2016 at 16:31

Doug, You said:

“Does a change in NGDP expectation cause a change in NGDP, or does a change in NGDP cause a change in NGDP expectations?

I would say that there is more of the latter than the former.”

I’d say the former. Monetary policy causes expected NGDP to change, which causes actual NGDP to change.

Harding, You said:

“That wasn’t really true, instead, it was the myth of Federal Reserve impotence.”

It was both. Both ideas were floating around. On the lags, I see that you ignored my comment, so I’ll ignore yours.

George, I don’t think Friedman was completely consistent on that point, but in any case the profession as a whole has interpreted it to refer to GDP. I seem to recall Mark Thoma criticized me once on this point, suggesting (correctly) that the consensus of the economics profession is that money affects the economy with long and variable lags. I think that is the consensus, but perhaps Friedman’s views were more nuanced.

Does anyone know the most recent estimates from the VAR literature?

As an example, I’m often criticized for claiming that if the Fed adopted a much easier policy in September 2008, after Lehman failed, it would have made the subsequent slump much milder. People dredge up the “lags” argument, which I believe reflects a mismeasurement of the effects of monetary policy. Consider that most economists seemed to think policy was expansionary in 2008, and then consider that the recovery didn’t begin until June 2009. Is it any wonder they are confused.

4. May 2016 at 18:52

“On the lags, I see that you ignored my comment, so I’ll ignore yours.”

-All right. When looking at data, I always make sure to use the same frequency for both series, thus, this:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=4odE

S&P500 bottoms out in March 2009, the INDPRO in June.

S&P500 tops out in October 2007, the INDPRO in November.

May 2010 shows a one-month long lag.

S&P collapses in October 2008, INDPRO first rises in October, then collapses in December and January while the S&P stays much more stable during the same period.

There’s clearly a one-to-three-month long lag between the movements of these variables. Whether that’s “long” or not is vague.

5. May 2016 at 05:15

Harding, That was a typo on my part, I meant you ignored my response on the deficit, not lags.

And your post is not how you estimate the lag. In any case, a 1 or 2 month lag would make me correct.

5. May 2016 at 10:24

How do you know expected NGDP causes actual NGDP to change?

5. May 2016 at 12:22

Sticky prices should mean lags. If looser monetary policy raises NGDP, sticky prices mean RGDP responds first and then prices rise later.

5. May 2016 at 13:00

-That wasn’t really true, instead, it was the myth of Federal Reserve impotence.

If you say so. The Federal Reserve’s Chairman during the period running from 1966 to 1970 was the same man who had presided over a rapid and successful stabilization of prices in 1951-52.

Per articles in The Wilson Quarterly, his successor (Arthur Burns) actually did believe that the inflation over which he presided for eight years had some other source than monetary policy.

6. May 2016 at 05:58

Oderus, That seems to be the most plausible interpretation of both theory and evidence.

Bill, I agree that sticky prices create a lag for the price level.

6. May 2016 at 07:29

Not sure what you mean by interpretation of theory; theory is what is, you use it to interpret the data. Where’s the evidence for such a causal relationship?

6. May 2016 at 12:44

“It would be like admitting that the textbooks were wrong when they tell students that the classical economists believed that money was neutral and that wages and prices were flexible.”

So what did the classicals believe or what distinguishes them from the Keynesians?

6. May 2016 at 12:59

Dr. Sumner,

Dr. Allen Meltzer advocated for the notion that war related created the “Great Inflation” in his book “A History of the Federal Reserve”. Dr. Meltzer interviewed the Chairman of the Board of Governors William McChesney Martin during the Johnson Administration for this book. Here is what Dr. Meltzer wrote:

“In the spring [of 1965], the Treasury was concerned about a possible slowdown of economic growth. During the summer, a new problem slowly emerged. Beginning in July 1965, President Johnson expanded the resource and financial commitment to the Vietnam War by announcing that additional troops would be sent to Vietnam.”

“Johnson did not want to reduce spending,raise tax rates, or have the Federal Reserve raise interest rates. Martin described the conversation.

‘He [President Johnson] didn’t want any increase in rates and he wanted me to assure him that there wouldn’t be. I couldn’t do that, of course. I had already made up my mind that we needed an increase in rates. So I did my best to break this to him as gently as possible but wasn’t so very successful in that he was absolutely convinced that I was trying to raise the rate and pull the rug out from under him. I said “Mr. President you know that I wouldn’t

do that to you even if I could.” He said,“Well I’m afraid you can.” And I said,“Well, I want to tell you right now that if I can [raise the rate] I will, because I think

you’re just on the wrong course. I’ve been perfectly fair with you. I was over here early this year.’” [1]

So the Chairman of the Board of the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) reports that President Johnson did indeed need to increase spending substantially and place tremendous pressure on the FRB to accommodate both the need for domestic economic growth and government spending by keeping interest rates low. Dr. Meltzer believe that this played an important role, although not the sole role, in creating “The Great Inflation”.

[1] https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/05/03/part2/Meltzer.pdf

7. May 2016 at 06:05

Oderus, The evidence is the correlation between asset prices and the business cycle, and the theory is what we use to explain why the correlation goes from expectations (embedded in asset prices) to business cycles.

Cyril, The standard classical model in the 1920s was a sticky wage model where demand shocks had real effects because wages were sticky.

The Keynesian model added the zero rate trap. And also the assumption that wage flexibility would not help.

David, Yes, I know that’s the standard view, but in the end it was monetary policy that created the Great Inflation, deficits were not large.

7. May 2016 at 08:41

Thanks. Then you think this passage is wrong

From Macroeconomics, 6th edition, by Ben Bernanke

“Classical macroeconomists assume that prices and wages adjust quickly to equate quantities supplied and demanded in each market; as a result, they argue, a market economy is largely “self-correcting,” with a strong tendency to return to general equilibrium on its own when it is disturbed by an economic shock or a change in public policy.”

7. May 2016 at 10:52

Sumner wrote:

“Oderus, The evidence is the correlation between asset prices and the business cycle”

Correlation is not evidence of causation.

See everyone? Anti-market monetarism rests on fundamental fallacies.

Global warming is “correlated” with pirate attacks. Is this “evidence” that priact attacks cause global warming or that global warming causes pirate attacks? Of course not, because the THEORY is weak if not absurd.

If stock prices and the business cycle are positively correlated, this along does not show any evidence that either changing stock prices cause the business cycle, or that the business cycle causes stock price changes.

7. May 2016 at 16:56

[…] Scott Sumner addresses the now oft-quoted statistic that the IMF has failed to predict 220 out of th…: he also argues that the stock market is neither a leading nor lagging indicator, but that it is coincident, something that I agree with. […]