Disgust with mankind?

In 1841, Alexandre Dumas famously described the changing attitude of the Paris newspapers as Napoleon marched toward their city after his escape from Elba:

The cannibal has come out of its lair.

The ogre of Corsica has just landed at the Gulf of Juan.

The tiger has arrived in Gap. The monster slept in Grenoble.

The tyrant crossed Lyon.

The usurper was seen sixty leagues from the capital.

Bonaparte advances with great strides, but he will never enter Paris.

Napoleon will be under our ramparts tomorrow.

The emperor arrived at Fontainebleau.

Yesterday, His Imperial and Royal Majesty entered his Tuileries castle in the midst of his loyal subjects.

(Frank Jacobs and Carrie Osgood produced a delightful map illustrating Dumas’s description.)

Alas, it appears these news headlines are apocryphal. Nonetheless, it seems unlikely that Dumas story would not have resonated with so many people if there were not a grain of truth.

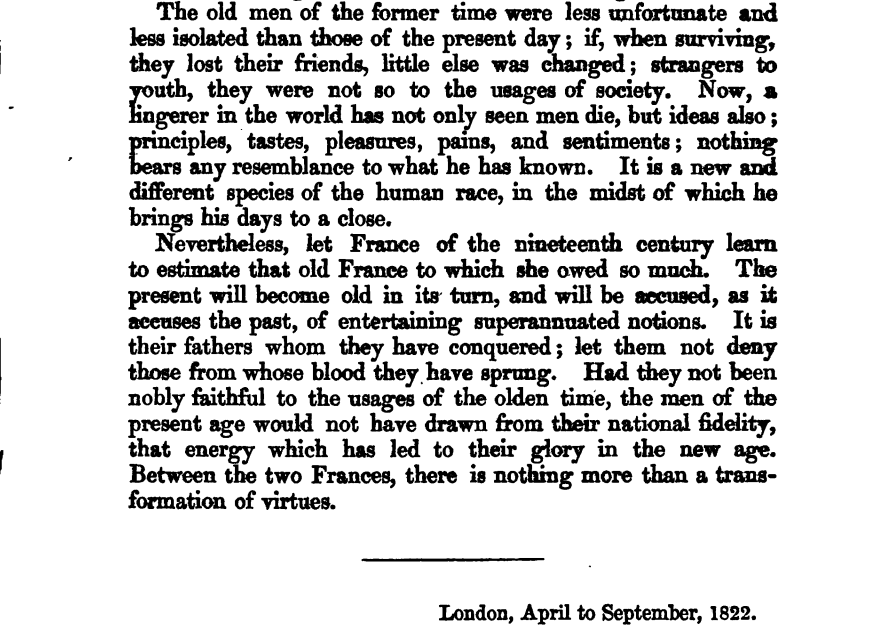

I just finished volume 2 of Chateaubriand’s excellent memoir. This caught my eye:

Bonaparte solemnly says he is giving up the crown, leaves, and returns nine months later. Benjamin Constant publishes his vigorous protest against the tyrant and changes his mind within twenty-four hours [ . . . ] Marshal Soult rouses the troops against their former leader; a few days later, he laughs aloud at his proclamation in Napoleon’s office at the Tuileries and becomes major general of the army at Waterloo. Marshal Ney kisses the king’s hands, swears to bring him Bonaparte locked in an iron cage, then delivers every soldier he commands to the latter. And the King of France? He says that at sixty he cannot imagine a better end to his career than dying in defense of his people . . . and he flees to Ghent. Faced with such an absolute absence of truth in human sentiments, such discrepancy between words and deeds, one feels overcome with disgust for mankind.

It doesn’t take much insight to see the same sad spectacle playing out in the conservative movement, where politicians and pundits that stomped on Trump’s political grave after January 6, have returned to licking his boots as he rose inexorably in the polls.

But should this cause us to have disgust with all of mankind? Surely the problem is just a few bad apples—people like Kevin McCarthy, Tucker Carlson and JD Vance. And yet, according to The Atlantic, almost the entire GOP apple is rotten:

Perhaps Romney’s most surprising discovery upon entering the Senate was that his disgust with Trump was not unique among his Republican colleagues. “Almost without exception,” he told me, “they shared my view of the president.” In public, of course, they played their parts as Trump loyalists, often contorting themselves rhetorically to defend the president’s most indefensible behavior. But in private, they ridiculed his ignorance, rolled their eyes at his antics, and made incisive observations about his warped, toddlerlike psyche. Romney recalled one senior Republican senator frankly admitting, “He has none of the qualities you would want in a president, and all of the qualities you wouldn’t.”

OK, the GOP is totally corrupt. Perhaps the Democrats are ethical. The Atlantic suggests that all politicians are the same:

[Romney] joked to friends that the Senate was best understood as a “club for old men.” There were free meals, on-site barbers, and doctors within a hundred feet at all times. But there was an edge to the observation: The average age in the Senate was 63 years old. Several members, Romney included, were in their 70s or even 80s. And he sensed that many of his colleagues attached an enormous psychic currency to their position—that they would do almost anything to keep it. “Most of us have gone out and tried playing golf for a week, and it was like, ‘Okay, I’m gonna kill myself,’ ” he told me. Job preservation, in this context, became almost existential. Retirement was death. The men and women of the Senate might not need their government salary to survive, but they needed the stimulation, the sense of relevance, the power. One of his new colleagues told him that the first consideration when voting on any bill should be “Will this help me win reelection?”

OK, but politicians are merely a small slice of humanity. And can you blame them for not wanting to lose their jobs? If only they had lifetime job tenure they would boldly stand up for what is good and true. According to Ross Douthat, even that’s not enough:

Tenure, in theory, should provide a counterbalance, enabling academics who survive the initial gauntlet to enjoy more freedom than the more precariously employed journalist. And there are certainly academics who use this freedom to the fullest. . . .

As Sarah Haider writes in a thoughtful post on the limits of tenure as a guarantor of diversity and debate, in many cases “tenure might simply make more room for social pressures to pull with fewer impediments.” Because “if keeping your job is no longer a concern, you will not be ‘concern-free.’ Your mind will be more occupied instead by luxury concerns, like winning and maintaining the esteem of your peers.”

Even tenured professors with job security are terrified of speaking out against unjust cancellations by the woke, and indeed often applaud these acts just as Soviet commissars vigorously clapped their hands during speeches by Joseph Stalin.

In polite society, it’s almost obligatory to say, “Most people are basically good”. Maybe, but what is the evidence for that claim? Are human beings qualified to offer an objective appraisal of the ethical value of humanity? I cannot dispassionately judge myself, how could I possibly judge all 8 billion people?

Sorry, but I’d like a second opinion, preferably from an alien life form. Someone unbiased. When we get GPT-6 or GPT-7, we can ask it to evaluate just how good the human race actual is. I suspect we are not going to like the answer.

PS. Have you ever hesitated before mocking the idiots who invaded the Capitol on January 6, not knowing if the listener is a Trump supporter? Here’s Chateaubriand:

It is hard to be born in times of improbity, in days when two men chatting together must be on guard against using certain words for fear of causing offense or making the other man blush.

PPS. Here’s another gem:

One of the things that most contributed to rendering Napoleon so repellent in his lifetime was his penchant for debasing everything. . . . While empires collapsed, he hurled insults at women. He enjoyed humiliating those he had brought low; he especially slandered and affronted anyone bold enough to resist him. His arrogance was indistinguishable from his happiness; he thought he grew in stature by diminishing others. Jealous of his generals, he blamed them for his own failings, because, as far as he was concerned, he could never have failed.

PPPS. And this:

Bonaparte, like the race of princes, wanted nothing and sought nothing but power, which he attained through liberty merely because he stepped onto the world’s stage in 1793. . . . The sophism put forward regarding Bonaparte’s “love of liberty” proves only one thing: how easily reason can be abused.

To be sure, Napoleon was a great man, with significant achievements. Indeed in some respects he was a genius. That other guy . . . er . . . not so much.

Read the whole thing (all 1300 pages.)