Odds and ends

1. Over at Econlog I have a post responding to Arnold Kling.

2. Tyler Cowen has a new post discussing the ideas of Kevin Erdmann. In my view Kevin is one of the most underrated thinkers in economics. He’s done a long series of posts on real estate, as well as related issues such as inequality. I differ with him on the natural rate, but only for the relatively trivial reason that I define the term differently than he does.

3. Joseph Stiglitz recently criticized Paul Krugman’s claim that our stagnation was due to an inability to cut interest rates far below zero. Here’s why Stiglitz think’s Krugman is wrong:

The real problem is people don’t have income, and when they don’t have income they don’t spend.

Well thanks for clearing that up! And the reason my car is going too slowly is not that I am not pushing hard enough on the gas pedal, it’s that the wheels are not rotating fast enough. I would have loved to see Krugman’s reaction, as well as his reaction to Ralph Nader’s recent advocacy of tighter money. I’m guessing Krugman won’t treat them with the same contempt that he views the gold bugs and inflation truthers.

4. Timothy Lee has a great article on Bitcoin:

Bitcoin hasn’t received the kind of hype in 2015 that it has in previous years. But outside the spotlight, the Bitcoin economy has continued to grow slowly but steadily. And in the last few weeks, the value of Bitcoin has soared. One bitcoin cost $236 at the beginning of October. Now, five weeks later, it costs $426.

No one is sure why the currency has had such a dramatic surge. But it’s at least partly a sign of growing investor confidence in the growth of the underlying Bitcoin economy. Here are five charts that show Bitcoin’s progress.

He has lots of evidence that Bitcoin is making big inroads into the real economy; it’s not longer just a speculative asset. Of course lots of people told us it was a bubble a few years back, even with the price was 1/10th its current level. I’d guess its price will continue to be wildly unstable, but I also suspect that it’s not just a flash in the pan. Bitcoin is another example of why bubble theories are useless. Suppose you had refrained from investing in Bitcoin based on earlier claims that it was overvalued at $30. You would have missed out on huge potential gains. For every bubble prediction that comes true, there is one that comes false. Asset prices are a random walk, and bubble theories add nothing useful to that fact. When you have an asset that’s value is easy to estimate, like 3-month T-bills, its value will be pretty stable. It’s harder to estimate the value of GE stock, so its value will be less stable. And it’s really hard to estimate the value of a biotech start-up, or Bitcoin, so their value will be very unstable. There will be dramatic ups and downs that look like bubbles, but that will be a cognitive illusion.

5. Tyler also discusses a new book by Garett Jones, called Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own. It’s one of the best non-fiction books I’ve read in quite a while (although admittedly I’m a slow reader, so I don’t read nearly as much as Tyler.) It’s no surprise that people with IQs of 105 make more money, on average, than people with IQs of 90. But the difference is modest. On the other hand, countries with average IQs of 105 are dramatically richer, on average, than countries with average IQs of 90. Of course there are lots of possible reasons for that (and exceptions to the rule), and Garett discusses a lot of interesting theories, some of which are based on behavioral economics research. The hypothesis that interested me the most is that higher IQ people (and countries) tended to be thiftier. Interestingly, the highest IQ countries tend to be in East Asia, and the smartest country in Europe is Switzerland. The book also has lots of interesting discussion of ways to boost IQ, the Flynn effect, etc., but I’m going to skip over the difficult problem of correlation/causation, and think for a moment about how Garett’s work interacts with Thomas Piketty.

Let’s suppose Switzerland and Singapore save more because their people have high IQs. According to Piketty, they’ll gradually get richer and richer, piling up huge current account surpluses. Now what should a good progressive think of that fact? If you are an “internationalist progressive”, who like all utilitarians believes the massive spending on social welfare in Western Europe should be redirected to the poor of Africa and Asia, then you’d be horrified by those two economic models, even though the conservative economic policies of Switzerland and Singapore benefited their own citizens. If you were a “nationalistic progressive”, which of course most are, you’d favor the European welfare state, and controls on immigration, because solidarity with the poor of your own country is more important than eliminating extreme poverty in the 3rd world. Then you might even like the Singapore/Swiss approach. It certainly seems to have won out in northern Europe.

6. It’s interesting to contrast Garett Jones’ book with another very interesting book that I recently read, The Moral Foundation of Economic Behavior, by David Rose. Garett says that higher IQ leads to higher levels of trust, which is important for economic development. David Rose also says trust is central to economic success, but focuses on cultural differences. He suggests that “guilt cultures” such as the West, have an advantage over “shame cultures” such as East Asia. That’s because people in a guilt-based society will be reluctant to cheat, even if they can get away with it. (Obviously I’m oversimplifying the story here, he’s well aware that lots of individual people cheat in all societies, even Denmark.) The book has many other interesting ideas. Conservatives would especially like David’s book.

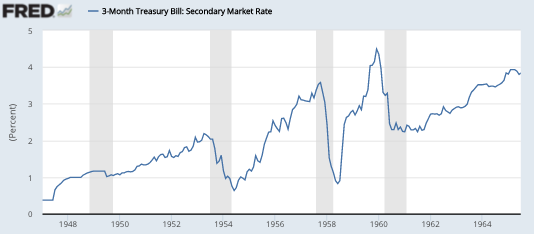

7. Timothy Lee also has a nice post on monetary policy:

The broader problem with Nader and Carson’s arguments is that the Fed doesn’t actually have that much control over interest rates.

Think of a guy driving along a winding mountain road. In one sense, he has total control over where the car goes. If he turns the steering wheel to the right, the car goes right. But that doesn’t mean he can drive the car wherever he wants. If he steers too far to the right, he’ll go through the guardrail and off the cliff. If he steers too far to the left, he’ll run into the mountain on the other side of the road.

The Fed is in a similar situation. It’s trying to steer a course between the twin evils of inflation and recession. If it keeps rates too low for too long, the economy will start to overheat, and inflation will get out of control. If the Fed raises rates too quickly, it’ll tip the economy back into recession. So it’s true that at any particular instant, the Fed can make interest rates go up and down. But the Fed doesn’t have that much leeway to raise rates if it wants to avoid hurtling over the cliff and into a big recession.

The European Central Bank did exactly that when it raised interest rates prematurely in 2011. That proved to be a huge mistake, because it tipped the eurozone economy into a double-dip recession.

Think of someone driving from Munich to Milan. Who determines the path of the car over the Alps? Is it the driver, or the Swiss engineer who designed the road? Both have some influence, but the one that directly controls the steering actually has the least influence. Ditto for the effects of the Fed and NGDP on interest rates. Most people don’t understand that point.

8. Lars Christensen points to a recent paper by Ryan Murphy and Taylor Leland Smith, which shows that NGDP shortfalls lead to statist policies. I’ve always believed that to be true, but mostly based on anecdotes like the New Deal, Obama, and the Argentine government’s shift toward statism after 2002. Now we have an empirical study, which shows how inflation hawks like Bob Murphy are inadvertently helping socialists such as Bernie Sanders. And the results hold even if you exclude the Great Depression and the Great Recession.

9. And last but not least, Paul Krugman hints at sinister policies that are dramatically improving the health of America’s Hispanic population, while slightly worsening the health of whites:

There’s a lot to be said, or at any rate suggested, about the politics of this disaster. But I’ll come back to that some other time. For now, the thing to understand, to say it again, is that something terrible is happening to our country “” and it’s not about Those People, it’s about the white majority.

I can’t wait to see Krugman reveal more details of the “politics” behind this outcome. Let me guess, the GOP will come out looking bad. (Seriously though, it is a really interesting graph, and not just because of white Americans, but also the huge gaps between say France and Sweden/Australia. They are not what I expected, and I have no idea what causes them.)