Nice guys finish in the middle of the pack

Here’s a thought: Was Ben Bernanke the most powerful “nice guy” in all of world history? Not all powerful people are as egotistical as Trump, or as ruthless as Nixon, but as far as I can tell nice mild-mannered college profs are almost never put in positions of great power. The world really is a pretty brutal place.

There is much to say about Bernanke’s memoir, so I’m splitting this up between TMI and Econlog. And I’ll skip the banking crisis, which is where Bernanke focuses most of his narrative. Eric Posner says he was authorized to bail out both Bear Stearns and Lehman. George Selgin says he lacked authorization (at least on Bagehotian grounds) for bailing out either bank. Bernanke says he was authorized to bail out Bear Stearns, but not Lehman. And I’m not qualified to have an opinion. So I’ll focus on monetary policy, something I do know a little bit about.

There is one big mystery that us policy nerds wanted answered in the memoir, and I did not find an answer. This is from a paper by Lawrence Ball, a highly respected macroeconomist:

The analysis starts with a puzzle about Ben Bernanke. From 2000 to 2003, when Bernanke was an economics professor and then a Fed Governor (but not yet Chair), he wrote and spoke extensively about monetary policy at the zero bound. He suggested policies for Japan, where interest rates were near zero at the time, and he discussed what the Fed should do if U.S. interest rates fell near zero and further stimulus were needed. In these early writings, Bernanke advocated a number of aggressive policies, including targets for long-term interest rates, depreciation of the currency, an inflation target of 3-4%, and a money-financed fiscal expansion. Yet, since the U.S. hit the zero bound in December 2008, the Bernanke Fed has eschewed the policies that Bernanke once supported and taken more cautious actions-primarily, announcements about future federal funds rates and purchases of long-term Treasury securities (without targets for long-term interest rates).

A number of economists have noted the difference between recent Fed policies and Bernanke’s earlier views- usually critically. In discussing one of Bernanke’s early writings on the zero bound, Christina Romer says “My reaction to it was, ‘I wish Ben would read this again'” (quoted in Klein [2011]).

Paul Krugman (2011b) asks “why Ben Bernanke 2011 isn’t taking the advice of Ben Bernanke 2000.” In criticizing Fed policy, Joseph Gagnon echoes Bernanke’s criticism of the Bank of Japan: “It’s really ironic. It’s a self-induced paralysis” (quoted in Miller, 2011).

That’s also my view, and I think it misses an even bigger issue, level targeting. Bernanke recommended the BOJ consider level targeting to make up for previously falling short of the inflation target. Level targeting can be seen as the justification for a higher inflation target in Japan, one of Bernanke’s ideas that Ball did mention.

I have a hard time believing that Bernanke is not aware of this paper, which contains lots of fascinating information, and the view out there that his views moderated after he became Fed chair. But he doesn’t really give us an answer in the memoir, particularly for the 2003 meeting that Ball insists was pivotal:

Sections IV-VI review the broader evolution of Bernanke’s views. I find that they changed abruptly in June 2003, while Bernanke was a Fed Governor. On June 24, the FOMC heard a briefing on policy at the zero bound prepared by the Board’s Division of Monetary Affairs and presented by its director, Vincent Reinhart. The policy options that Reinhart emphasized are close to those that the Fed has actually implemented since 2008; Reinhart either ignored or briefly dismissed the more aggressive policies that Bernanke had previously advocated.

In the discussion that followed the briefing, Bernanke joined other FOMC members in agreeing with most of Reinhart’s analysis.

Shortly after the meeting, Bernanke began writing papers that took positions very close to Reinhart’s-some with Reinhart as a coauthor. Clearly, the analysis of the Fed staff in 2003 was critical in changing Bernanke’s views about the zero bound.

At first glance, Bernanke’s sharp change in views is surprising. In 2003, he was a renowned macroeconomist who had studied the zero-bound problem extensively and expressed strong views about it. Yet he quickly accepted a different set of views when Reinhart presented them.

Why did the positions of the Fed staff influence Bernanke so strongly?

This question is difficult to answer, as we can’t observe Bernanke’s thought processes. Yet we can develop hypotheses based on research by social psychologists, who study group decisionmaking.

Based on this research, Section VII suggests two factors that may help explain Bernanke’s behavior. The first possible factor is “groupthink” at the FOMC, a tendency of Committee members to accept a perceived majority view rather than raise alternatives that might be unpopular.

The second is Ben Bernanke’s personality, which is typically described as “quiet,” “modest,” and “shy”- traits that might make him unlikely to question others’ views.

As I general rule, I feel somewhat uncomfortable looking for psychological explanations. And in the end I’m going to defend Bernanke, or at least 80% defend him from the charge that he caved in to the FedBorg. But first I’d like to push ahead with this line of thought.

What are we to make of the fact that Bernanke’s memoir doesn’t explain this 2003 turnabout? One possibility is that he’s embarrassed, and would just as soon cover up what happened. But I don’t think that is correct. The memoir is often brutally honest, and there are cases where he blames himself for things that (in my view) he should have blamed others. He’s too hard on himself. Furthermore, I believe that a close reading of the text provides a more nuanced interpretation of what when on.

Here’s my reading:

1. Bernanke came to the Fed with lots of ideas about how policy could be improved. He also had lots of ideas about the appropriate policy process—which he thought should be more collegial, less dictatorial than under Volcker and Greenspan—more like a college committee.

2. Bernanke quickly found out that the Fed is a very powerful institution, with a life of its own. And it’s embedded in a difficult and highly complex policy environment in Washington.

3. Bernanke felt that policy was most effective if credible, and that meant you needed to avoid lots of close 6 to 5 votes. You wanted enough support so that the markets would believe the Fed would carry through with its policies.

4. In this difficult environment, Bernanke decided to pick his battles, and focus on implementing as many reforms as he could, given the political constraints. BTW, in a book of very few revelations, the biggest comes near the very end, where he talks about the struggle to implement QE3. There was intense pressure within the Fed to “taper”. Bernanke had to use all his political skills to keep it going throughout 2013. And where does Bernanke say this pushback came from? Not Fisher, not Plosser, but rather the Obama appointees, Stein and Powell! In the end they were team players that went along, but he knew he could only push them so hard. If you don’t think Bernanke faced intense political pressure, just think about the fact that even the Obama appointees were highly skeptical of his monetary stimulus. (Even weirder, the people he could rely on (Rick Mishkin, Don Kohn, etc.) were typically Bush appointees.)

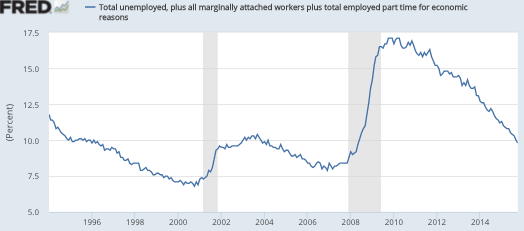

5. Bernanke decided to focus first on fixing the financial system, which was a mistake in my view. The Fed (and Bernanke) sort of assumed that rescuing the banking system would rescue the macroeconomy. By March 2009 they discovered that that assumption was wrong. And it wasn’t just because of the rising unemployment, which is a lagging indicator. Stocks kept plunging lower and lower, reaching levels that suggested fear of an outright depression. And they are not a lagging indicator. The recession was far worse than expected. The big stock rally did not occur after banking was saved, it occurred after the Fed turned its attention to monetary stimulus, in March 2009 (i.e. QE1). BTW, Bernanke mentions stock prices a lot in the memoir, which reminds me of my narrative of the Great Depression.

6. In addition to implementing his academic research on the importance of saving the banking system, he also implemented some of his monetary research. Most notably, he did QE and then he got the Fed to adopt an explicit 2% inflation target (a bit higher than some wanted.) He got the Fed to try to reduce long term bond yields, by buying long-term bonds. Then he got the Fed to commit to low rates for a long period. And then low rates until the economy improved, and then QE that was open-ended, until the economy improved. That’s a lot, and I wouldn’t blame Bernanke for being exasperated by critics like Ball, Krugman and yours truly.

7. But . . . you knew there was a but. He didn’t adopt the more controversial ideas, such as a higher inflation number, or level targeting, or NGDP target (perhaps combined with level targeting). It would have been really hard to sell these controversial ideas to the Fed, they would have been highly controversial in Congress, and he didn’t want a badly split Fed implementing a policy that required credibility. A policy that the markets would have to trust the Fed to persevere with. Unfortunately, those more controversial ideas were the most effective options, indeed one reason they were so controversial is that they are quite powerful.

It might help if I put my views on Bernanke into perspective. Here’s how I would grade some major central banks, and central bankers:

A: Reserve Bank of Australia (with an easy test)

B: Bernanke, Draghi, Carney, Kuroda

C: Fed under Bernanke

D: Pre-Kuroda BOJ, the ECB under Draghi

E. Trichet, and ECB under Trichet

You might notice that in some cases I grade central bank heads higher than the institution they lead. Bernanke was working very hard on the inside to push the Fed in a more dovish direction. I’m not sure those of us on the outside appreciate how difficult his job was. Ditto for Draghi.

Am I getting soft? Hell no! I’m just as critical of the Fed as before. If they had been more supportive of Bernanke, policy would have been more expansionary.

Do I have any evidence to justify being such a softy regarding Bernanke? First of all, I’m not that soft. I regard his memoir as having fallen short in its monetary policy analysis. He needed to point out more forcefully that the Fed should have done more. He admits to some mistakes, such as not easing policy in September 2008, but he should have said the policy regime was not up to the task of what needed to be done in 2008-09. So I think being at the Fed did change him somewhat. A Professor Bernanke looking at the Fed from the outside could have written a better narrative of what went wrong with monetary policy, and almost certainly would have had views similar to many of us who favored more “Rooseveltian resolve”. But if I am grading him on the actual job he did, under the circumstances, I have to say that he worked really hard, and got an institution that was as stubborn as an old mule to do far more than the ECB, or some other central banks.

And finally, I have one powerful piece of evidence for giving Bernanke somewhat of a break. No one can doubt the views of Janet Yellen. She has always been extremely worried about unemployment. She’s sided with the doves. And yet now some consider her a hawk, given her recent statements on the likely increase in interest rates. A theory that the FedBorg did some sort of mysterious brain transplant on Bernanke might be just barely credible. But two consecutive brain transplants? Much more likely the Fed is far more inertial than we on the outside tend to assume.

If Bernanke was not able to implement an appropriately stimulative policy, with all his vast qualifications as a Depression scholar, and his reputation as a dove on Japan, then we need to stop looking for perfect Fed chairmen and start thinking about a policy regime that makes massive and persistent demand shortfalls less likely. A regime that makes the Chairman’s job as easy as in Australia. I believe that regime is NGDP, level targeting. But it will only happen AFTER the economics profession as a whole reaches a consensus that this is a sensible policy. At Econlog I have some further thoughts on that issue, and on the memoir as a whole.

This post from a few years ago (based on a Marcus Nunes post) examines the Ball hypothesis in more detail.