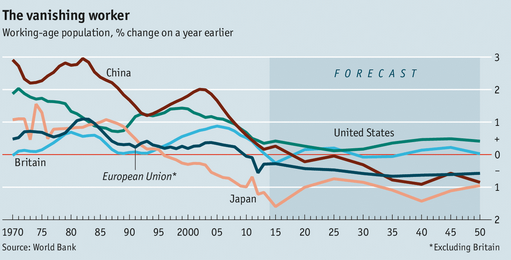

Why the Japanese economy is slowing, and will continue to slow:

From Free Exchange:

Check out the Japanese labor force “growth” rate in 2015. Soon we’ll be discussing the “trend rate of shrinkage” in various OECD countries. We’ll need a whole new vocabulary.

PS. I just saw that the unemployment rate in Japan fell again in October, to 3.5%. That’s the lowest rate in more than 16 years. Gee, I wonder when their unemployment rate will start showing the effects of the “recession” that Japan fell into eight months ago. Anyone want to offer a guess?

Meanwhile there is this tidbit:

The number of employed persons in October 2014 was 63.90 million, an increase of 240 thousand or 0.4% from the previous year.

Japan’s workforce is shrinking rapidly, and to make things worse they are in a “recession,” and yet by some wondrous and strange miracle their employment keeps rising!

Yup, that April sales tax increase sure was a disaster. If they’d only listened to Paul Krugman the unemployment rate today would be . . . 3.5%?

PPS. And file this FT piece under, “why the media should never again discuss inflation”:

The sharp fall in oil prices provided an immediate and welcome fillip to Asian economies heavily dependent on energy imports, although the inflation-sapping effect was a mixed blessing for Japan and China.

. . .

For Japan, the world’s third-largest oil importer, lower input costs stand to help manufacturers and households, in turn lifting wages and the economy. But lower import bills also frustrate government efforts to lift the economy out of deflation through aggressive monetary easing.

Japanese core inflation last month fell to 0.9 per cent, a 13-month low. Economists say a further erosion in inflation from lower oil prices will raise expectations that the Bank of Japan will once again beef up its stimulus efforts.

That would lead to a steeper depreciation in the yen, which in turn could mitigate the positive impact of falling oil prices on the purchasing power of Japanese households.

Yes, and winning Megabucks would be a mixed blessing for me—I’d become ultra-rich, but it would frustrate my goal of minimizing my tax liability.

PPPS. Neo-Fisherism is now almost indistinguishable from MM.

Tags:

28. November 2014 at 16:14

excellent blogging. Yet something should be said about the long-term effects of a monetary policy that suffocates an economy the yen has more than tripled in exchange rate since the 1980s and Japan has through most of that suffered from mild deflation and very slow growth.

Moreover, cultures and economies are mutable. We could see a norm of retirement-age workers working part-time or more female entrants to the Japanese labor force, or perhaps even immigration to select industries such as fisheries or canneries.

I still contend that what we see in Japan is the residual and embedded effects of an asphxiating monetary policy.

28. November 2014 at 17:04

I guess monetary stimulus could always make wages go up in Japan. They’ve got low unemployment, but wage growth isn’t too hot – especially outside of the Key Export Sectors. And it would put a ton of pressure on the government to start allowing in more immigrants, and pressure on the businesses over there to increase the hours and labor force participation of women, the old, and teenagers.

But yeah, they probably need some structural reforms too. I’ll admit I’m biased in pointing out my last paragraph, since I want them to spend a ton of money on robotics and automation to meet growing labor needs before they give up and allow in more immigrants – that would be good for overall world productivity.

28. November 2014 at 19:04

As you carefully note, with admirable restraint, even a cursory examination of data beyond the headline GDP growth number casts doubt on the Japanese recession story. Yet the GDP number keeps getting repeated and repeated. Sigh.

Then there’s the Japanese-language news, it’s the best market for new college grads in many a year.

Reporters are schooled in asking questions, it shouldn’t be hard to get someone to give a quick overview of ancillary data. And if a journalist is too embarrassed to show they’re illiterate, they can access standard labor market statistics without knowing a word of the language. Not that many publications have so much as a stringer in Tokyo….

I’m glad there are a few people who realize a “flash” GDP release needs to be paired with complementary data. It’s bad when journalists don’t push beyond the headline, it’s worse when an economist fails to do so. If it’s the pressure to be the first to “blog” a breaking topic, then, well, again kudos for being careful.

28. November 2014 at 19:20

I’m sort of confused about Japan, having read all the recent posts on the country. Why do people expect that hitting a 2% inflation target would increase GDP growth? It doesn’t seem like unemployment would drop under 3.5%, so wouldn’t it have to increase labor productivity growth somehow? Or is it expected that higher inflation could lead to more labor force participation?

28. November 2014 at 21:06

Benjamin Cole,

I’m inclined to agree with you!

28. November 2014 at 23:29

Thanks Travis. Some people think an economic cure-all this is a zero percent rate of inflation. My economic cure-all is print more money.

29. November 2014 at 06:24

Scott,

As I have said repeatedly before, you’re confusing cause and effect. Economic growth drives the birth rate and immigration….not the other way around.

In a country like Japan, where you have a large number of “under-employed” workers and large numbers of people in low productivity jobs, high economic growth can be achieved with little or no increase in the work force.

A few additional comments.

It is very easy to immigrate to Japan. Student visas are easy to be had and allow the holder to “officially” work up to 28 hours per week. Getting a work visa upon completion of studies is also very easy. The only reason there is not more immigration is a lack of good opportunities.

Same thing, for the birth rate. If there were better prospects for economic growth, the birth rate would increase. (And BTW, you haven’t responded to my comments on how the Korean birth rate has fluctuated with the recent economic cycle in Japan.)

Also I think you have no conception of how unproductive the Japanese work force currently is. 20 years of stagnant growth with no ability to fire workers results in a huge number of workers doing very little.

Finally as I have noted before the methodology for the unemployment number is different in Japan. Studies have suggested that if Japan used the same question used in the U.S. CPS, i.e. have you actively looked for work in the last four weeks, instead of asking if you have looked in the last one week, then the unemployment number would be somewhere between 60 and 100% higher in Japan.

29. November 2014 at 06:25

Benjamin Cole,

Yes, monetary policy has been asphyxiating. But high taxes and regulations have been much worse of a problem.

29. November 2014 at 07:11

Krugman on the liquidity trap:

“But at this point we’ve been at the zero lower bound for six years; we’ve seen a 400 percent rise in the monetary base without a takeoff in inflation; we’ve seen record peacetime deficits go along with record low long-term interest rates.”

It’s been longer with Japan and greater deficits. I think it’s just that QE isn’t as effective as conventional monetary policy, especially when the central banks aren’t sending strong signals as they would with an NGDP path level target.

29. November 2014 at 07:12

Ben, Yes, there may be some long term effects.

Brett, It may raise nominal wages, but probably not real wages. But it will raise real income.

Mike, It’s shocking how little American intellectuals know about Japan.

BJ, It might lower unemployment a bit more, but not too much.

dtoh, You said:

“It is very easy to immigrate to Japan.”

So any starving farmer in Bangladesh can immigrate to Japan whenever they wish? Why don’t they?

And BTW, you haven’t responded to my comments on how the Korean birth rate has fluctuated with the recent economic cycle in Japan.”

I have no idea why the Korean birth rate would fluctuate with the economic cycle in Japan. But the birth rate in all prosperous East Asian countries is as low or lower than in Japan. Even Chinese cities like Shanghai have a birthrate of about 1.0, and it’s not due to government restrictions (the birthrate is much higher in the countryside.) East Asian prosperity brings ultra-low birth rates everywhere. It’s that simple.

You said:

“In a country like Japan, where you have a large number of “under-employed” workers and large numbers of people in low productivity jobs, high economic growth can be achieved with little or no increase in the work force.”

I don’t know of any economic model where printing money can boost productivity. I’m sure there are policies that would boost productivity, but printing money isn’t one of them.

I agree the actual unemployment rate in Japan may be higher, but what matters is the unemployment rate relative to the long term trend rate. And that is quite low, suggesting they are near the “natural rate” of unemployment.

29. November 2014 at 07:14

If they hadn’t done the consumption tax, they’d probably be closer to their 2 percent inflation target which is Krugman’s point. A shrinking workforce should put upwards pressure on inflation.

29. November 2014 at 07:14

Peter, You have a lot of catching up to do. QE is not a policy it’s a tool. Monetary stimulus has NEVER failed in Japan. I would suggest reading some of my older posts on Japan.

29. November 2014 at 07:15

Peter, Actually the consumption tax sharply raised inflation in Japan.

29. November 2014 at 07:35

Scott,

Should have read “how the Korean birth rate has fluctuated with the recent economic cycle in Korea.” Typo

Yes, a poor starving Bangladeshi farmer could immigrate to Japan if they could afford the airfare and tuition to a Japanese school. The Pilgrims did not charter the Mayflower for free.

No one is arguing that monetary policy will improve productivity. But your argument, at least judging from the title and accompanying graph, suggests that the economy is slowing because of demographics. It’s not. It’s slowing because of disastrous tax and regulatory policies.

And I agree, that a historically low employment rate would normally suggest that a country is getting close to the real growth limits that can be achieved with monetary policy. (Unless, as is the case of Japan, your LPE is still below historical norms and you’ve had a shift in your employment patterns to part time work.)

29. November 2014 at 07:36

LPE > LPR

29. November 2014 at 09:15

BJ Terry — the point of triggering inflation is that you it by creating more money.

That’s the real goal, as expressed by benjamin cole. However, money printing understandably alarms most people, so you have to sell the policy by advocating for inflation.

I’m curious to learn more about how printing money will trigger economic growth. I supposed it is possible to do this if you just targeted the people who don’t have any money — on the other hand, wouldn’t that also reduce productivity. Most people if you money printed them a living wage would stop working altogether.

29. November 2014 at 10:48

The definition of recession is two consecutive quarters of growth decline.

Google the word for crying out loud.

If you want to redefine the word, then fine, try it, but at least admit that your intention is to redefine the word.

29. November 2014 at 10:51

In our centralized counterfeiting society, it is better, ceteris paribus, for aggregate spending to rise by virtue of falling prices (yes this can and does happen, especially when coming out of a recession), than by inflation from the counterfeiter.

29. November 2014 at 11:15

Noah Smith on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/Noahpinion/status/538559854047023105

“Krugman turned out to be right about something that I had suspected he was wrong about.” http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/11/28/the-end-of-artificially-low-rates/?_r=2

29. November 2014 at 11:58

Perhaps we need to be tracking more fully GDP/worker (productivity), and publicizing it and changes, as well as total GDP? If GDP stayed constant with the falling # of workers, that would be because of increasing productivity.

Printing money, rather than borrowing it, seems like a good idea any time inflation is below target, i.e. for the last 25 years or so in Japan? Since their huge 1989 Tokyo property-bubble pop. To discuss the Japanese economy without explicit discussion of how the banks haven’t yet handled their property loans from the 80s boom seems weak.

29. November 2014 at 16:26

Why does the shrinking number of workers matter so much to real growth when most workers (in most of the OECD, not just Japan) create almost no value?

29. November 2014 at 19:26

“If you want to redefine the word, then fine, try it, but at least admit that your intention is to redefine the word.”

Priceless coming from an an-cap

29. November 2014 at 21:51

Ben J:

Why? I do not deny that my definitions for words differs from yours. That you choose to use definitions that differs from the ones I use. I never fail to define a term when prompted. I will just reject any attempts to compel me to change my definitions to yours, unless there is a good reason given.

But this isn’t about me. This is about Sumner and his definition of recession that differs from the commonly accepted definition. I don’t compel him to change his definition.

I am not being a hypocrite.

30. November 2014 at 03:33

dtoh:

Measuring structural impediments across time and across nations is nearly impossible, but I gather Japan has initiated many structural reforms in the last 20 years, especially in retailing and employment.

A recurrent theme in right-wing circles, whenever an economy slows, is to call for lower taxes on rich people, and less regulations.

How the USA boom-boom-boomed in the 1960s must stupefy many.

90% top MTRs, and regulations on transportation, finance and telecommunications that seem overbearing by today’s standards, Add in Big Labor, Big Steel, Big Auto, Big Oil you name it. The 1960s USA was a regulated and taxed economy, but it boomed.

I actually concur that taxes should be low, and regulations light. I would cut federal spending in half.

But we saw Japan boom-boom in the 1960s-80s, and the USA boom in 1960s and then do well from 1982-2007 with the usual variety of modern-state structural impediments.

A nation can prosper with structural impediments; it cannot prosper with monetary asphyxiation.

That is bedrock of modern economics. All else is commentary.

30. November 2014 at 03:49

Benjamin Cole,

I agree. You can certainly asphyxiate an economy with bad monetary policy.

And I agree an economy can boom with high taxes and constrictive regulation…. but

I don’t agree that a modern economy can boom with high taxes and excess regulation. It’s only possible in an economy where you can throw labor and capital into concentrated industries with large firms and undeveloped markets. The U.S. did it in the 60s. The Soviets did it in the 20s.

30. November 2014 at 05:20

dtoh,

First off I want to say I always appreciate your comments on Japan. I’m not as knowledgable as you, but I have to say my inclination from what I’ve read is to agree with you. And, as far as I’ve been able to determine, immigration law is not the problem. So I agree with you there too.

‘Excess regulation’ is a problematic term to use, though, especially once you admit that cross country comparisons of regulation are hard. On the one hand, obviously all countries would be wise to eliminate own their ‘excess’ regulations. On the other, it gives us no guiding principal across countries as to which types of regulations are necessary.

So as nations stumble around trying to remove their ‘excess’ regulations, what are they supposed to use to guide them? Well, it’s not rocket science, you proceed conservatively and roll back regulations one at a time and wait to see what effect the repeal has on your economy. But this requires a proper monetary background! A positive supply side reform + a bad CB can mean the impact of the reform is lost on the public.

So I’m not saying money alone will fix Japan. Its not sufficient, but it is necessary. Undertaking reforms (even pretty good ones) with a bad CB can serve to merely tarnish the reputation of those reforms.

30. November 2014 at 07:34

Nick,

I actually think it would be easy to fix a big part of the problem with a few simple changes.

1. Significantly reduce rates on all taxes on capital including wages and bonuses paid to an owner.

2. Make employment “at will” for all new hires starting today. I.e. you can terminate an employee for any or no reason immediately and with no severance pay.

3. Make leases enforceable. I.e. you can quickly evict a tenant for non-payment of rent. This makes it possible for new businesses to easily and cheaply acquire premises.

4. Eliminate all stamp, registration and transaction taxes.

There is a bunch of other nuisance stuff, but these are the main ones. As I have said to Scott, I think you could get 7% sustained real growth if you did implemented these changes.

All that said, none of this is going happen in the short or intermediate term, which IMHO is why growth in Japan will continue to stagnate.

Also totally agree that a bad CB can mess all this up.

30. November 2014 at 08:24

dtoh, You said:

“No one is arguing that monetary policy will improve productivity.”

I thought you were. Perhaps easy money could slightly boost the LFPR, but I’d expect any gain to be very small.

Again, I think supply side reforms could boost Japanese per capita GDP to US levels, but I think there is almost zero chance of those reforms occurring. Ditto for population growth.

As far as Immigration, if you are correct then I wouldn’t say it’s “easy” for people to immigrate to Japan. There are plenty of high paying blue collar jobs in North Dakota–do you think it is “easy” for America workers to move there?

Tom, There are much better ways of raising inflation to target than printing money. Level targeting, for instance.

30. November 2014 at 08:57

Scott,

By extension of your definition, it’s not easy to immigrate anywhere. The question is whether the country in question put ups restrictions or makes it more difficult to immigrate. In Japan the regulatory hurdle is low so I would argue it’s “relatively” easy to immigrate to Japan.

More interesting however is your belief that Japan can attain US per capita levels. How long will it take? We can test my 7% real growth hypothesis.

1. December 2014 at 10:38

dtoh, I don’t think Japan could reach US levels with the reforms you propose, I think they’d need at least 10 or 20 TIMES more reforms. It would take at least 20 or 30 years, maybe catching up at 1%/year.

It seems like it’s much easier to immigrate to the US than Japan, but then I may be missing something in the equation.

1. December 2014 at 12:27

http://www.bbc.com/news/business-30279644

Japan, downgraded, but not by much. But if domestic reaction to the downgrade is against Abe then it will be the end of Abenomics in about two weeks time.

1. December 2014 at 16:19

Scott,

What other reforms?

1% for 30 years does not catch Japan up to the U.S.

In general it’s 10 times easier to immigrate to Japan than it is to legally immigrate to the U.S. And if you’re an uneducated Bangladeshi farmer it’s a 100 times easier to immigrate to Japan.

1. December 2014 at 17:54

dtoh, I’m no expert on Japan, but based on what I’ve read there are 1000s of barriers to growth. Real estate restrictions are important; housing, farming, retailing, and many other sectors need reform. But I couldn’t give you a good answer without much more study.

If it were truly easy to get into Japan then I believe lots more people would be moving there–it’s a rich country.

1. December 2014 at 18:00

Scott,

Scott more people would be moving to Japan if there were adequate jobs and the income from those jobs made up for the cost of immigration and the loss of utility from being away from family, etc.

And I know a fair bit about the barriers to growth in Japan. I agree there are 1000 things that could be fixed, but the four things I listed will solve most of the problem.

1. December 2014 at 20:16

My understanding is that housing/real estate restrictions are not as bad in Japan as in the US and Europe? Annual housing stock growth in Tokyo over the past decade was about 2%, vs around 0.8% in San Francisco and London, and around 0.5% in New York and Paris. (And the difference is not explained by demand; rents in Tokyo have fallen while those in the other cities mentioned have skyrocketed due to housing shortages.)

2. December 2014 at 04:38

Anon256

You’re correct. Real estate restrictions are not too bad in Tokyo. Residential rents in Tokyo have not really fallen except at the very high end of the market.

2. December 2014 at 04:41

Anon256,

Actually demand is pretty high. Residential occupancy rates are extremely high, but the problem is that renters don’t have enough income to pay higher rents.

2. December 2014 at 08:15

dtoh, Sure, I mostly meant that the lower housing growth rates in economically-active Western cities were the result of (much) worse regulation, not less demand.

2. December 2014 at 09:02

Anon256

Yep… and also Tokyo has a lot more vertical space to build than a lot of cities.

2. December 2014 at 09:06

Re: immigration to Japan. I don’t know of the legal or regulatory restrictions, but culturally it’s very difficult to move to Japan. The Japanese don’t accept newcomers.

2. December 2014 at 09:09

I was under the impression that it was difficult to get permission to build high rise condos in Tokyo. If not, why is it mostly a low rise city?

2. December 2014 at 09:10

And I thought Japanese employers were having trouble finding workers.

2. December 2014 at 16:12

Scott,

It’s hard to build high rise condos in any city. Historically, Japan has been low rise due to earthquake safety concern, which means there is a lot of room to build up now that engineering/design has improved. Without going into the history of regulation, it’s relatively easy to get building permission as long as you meet the FAR (floor area ratio) and sun shade restrictions.

2. December 2014 at 16:14

Scott,

And with respect to finding workers, “Never argue from a no-price change.” Or something like that.

2. December 2014 at 16:16

Charlie Jamieson

“The Japanese don’t accept newcomers.”

That has not been my experience.

3. December 2014 at 11:57

But lower import bills also frustrate government efforts to lift the economy out of deflation through aggressive monetary easing.

*headsplode*

Yes, curse those positive supply shocks! Also, productivity improvements!

3. December 2014 at 12:43

TallDave,

I feel the same way. This is exactly what I’m noticing in article after article this week regarding oil prices. I honestly had no idea how few business and economics writers don’t understand the difference between deflation and price declines due to supply factors. I’m not an economist myself and it doesn’t seem like such a difficult concept to grasp, so I’m really puzzled.

3. December 2014 at 12:45

That should read “I honestly had no idea how MANY business and economics writers don’t understand the difference between deflation and price declines due to supply factors.” Such a *headsplode* that I was trying to say two things at once and ended up making it a double negative.

3. December 2014 at 16:48

dtoh, Real estate should be cheap in any city where there are no severe building restrictions. And yet I’ve read that condos in Tokyo are expensive.

Adam and Talldave, I’ve noticed the same thing.

3. December 2014 at 21:53

Scott,

1. Condos in Tokyo are less than NYC or London (despite higher building costs.)

2. It depends on marginal supply and demand does it not?

4. December 2014 at 06:13

Scott,

Just one other point on this. The main factor restricting supply is that there are not many large bundles of land available for high rise construction. It is very difficult to acquire enough contiguous parcel of land to build a large building. One of the main reasons for this is high transfer and capital gains taxes on land sales and very low real estate taxes. Which…. is why I listed them as key reforms.