Finally! Proof that the Keynesian model is true

Matthew Klein has a useful piece in the FT that shows the way that government spending has fluctuated over time. The data is reported as if changes in G passed through one for one into changes in GDP. It wasn’t clear to me why this data was important, but then I’ve never really understood the appeal of Keynesian economics. That is, until I read the explanation from Jim Edwards over at Business Insider:

Conservatives Will Hate This: Proof That Government Spending Cuts Hurt Economic Growth

Edwards explained to me what I missed in the Klein article–proof that government spending boosts GDP:

It’s the oldest battle in politics: Whether cutting government spending helps or hurts economic growth.

The Financial Times has done everyone a favour by publishing a series of charts on how US government spending contributed, or detracted from, GDP growth. And the conclusion is pretty severe:

… austerity subtracted about 0.76 percentage points off the real growth rate of the economy between the middle of 2010 and the middle of 2011. If real government spending had remained constant at mid-2010 levels and everything else stayed constant, (yes we know these are big assumptions) the US economy would now be about 1.2 per cent larger.

There’s a secondary conclusion, too: War is good (economically), it turns out.

Edwards doesn’t bother using quotation marks, but the longer paragraph is taken from Klein.

Update: Travis told me the lack of quotation marks was Yahoo/Finance’s fault, not Edwards.

Now you might notice that Klein refers to the “big assumptions,” which suggests that he doesn’t see his article as providing definitive proof that conservatives are wrong about fiscal stimulus. Fortunately Edwards has the courage of his convictions. He points out that Klein has the data to back up his claims:

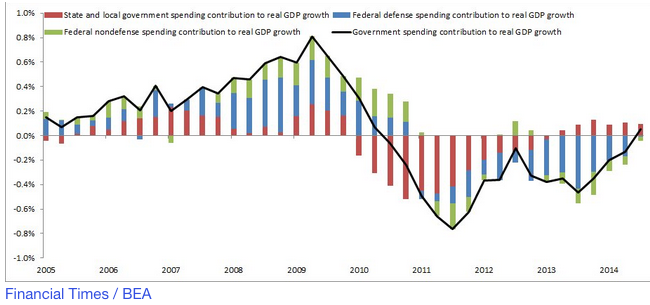

This chart, from the FT’s Matthew Klein based on data from the BEA, seems to show that government has a pretty straightforward effect on GDP. When spending goes up, it adds to economic growth. When it goes down, it subtracts from it and hobbles the economy:

Perhaps you are having trouble seeing the “proof.” Let me help you. The red is the state and local government contribution to growth. This is the change in spending divided by GDP. The blue and green are the federal defense and non-defense contribution to growth. Add up all three and you get the total government spending contribution to growth. So the graph shows that changes in government spending have a “pretty straightforward effect” on GDP. The evidence is clear.

Still don’t see the evidence? OK, let’s try again. Each color shows the contribution of changes in government spending. It’s the actual change divided by GDP. Add them up and you get the black line. That’s the total contribution of changes in G to GDP. That’s pretty clear evidence, isn’t it?

Still having trouble? OK, read the article again, and think deeply about the Keynesian model. It’s sort of one of those vase/face deals—if you think hard enough you’ll eventually see what Edwards sees, that these graphs prove that conservatives are wrong. If you still don’t see it . . . well just try harder . . .

PS. Tyler Cowen has a very good post on Keynesian economics. Unfortunately he gets a bit wobbly in point 15, and concedes too much. I suggest deleting point 15 from his list and in its place repeating point #1. Better yet repeat point #1 a hundred times in a row.

PPS. Klein’s piece is actually pretty useful as a source of data, as long as you realize when you are reading the piece that he is not talking about the stance of fiscal policy, he is talking about government spending. Fiscal policy involves both tax and spending changes, and the numbers would look radically different if you wrote a piece evaluating the impact of fiscal policy.

HT: Marcus Nunes

Tags:

27. November 2014 at 19:37

Edwards didn’t use quotation marks because he block-quoted in the article on Business Insider’s site:

http://www.businessinsider.com/data-government-spending-cuts-hurt-economic-growth-2014-11

Unfortunately, that quote was not block-quoted for some reason at Yahoo Finance.

27. November 2014 at 20:29

It must be nice to be able to simply assume exactly the point he’s claims to “prove” and have mainstream media accept it as fact. Shall we call it Keynesian privilege?

27. November 2014 at 21:51

I never was able to see those three dimensional ships from the pictures. Also anytime I hear someone claim that war is good for the economy I have a decided tendency to immediately tune them out. Even if it helps numbers go up(which I still find doubtful), it does not help the economy.

27. November 2014 at 22:19

I’m not confident in my ability to read graphs. Which of these sentences, if any, describes what the graph is showing us?

1. As G increases, G/GDP increases.

2. As G increases, GDP increases.

3. As G increases, GDP – G increases.

It looks to me like it’s showing #1, but that would tell us nothing about the effect of government spending cuts on GDP (maybe that’s the joke). #2 looks like it would only support the “Government Spending Cuts Hurt Economic Growth” thesis superficially, since not all dollars of GDP are created equal (maybe that’s the joke). I include #3 because I think it would make a convincing graph, and the author thought he was being convincing. But it doesn’t look like #3.

Hypothetically, what are some simple and plausible correlations that would give Edwards a better case?

27. November 2014 at 22:57

About Tyler’s points 1 and 15: if US austerity was offset nicely by monetary policy, isn’t Japan a counterexample? There tightening of fiscal policy has lead to a big effect even though monetary policy has been loosened at the same time.

I see two examples pointing into opposite directions.

28. November 2014 at 00:06

Andy, Japan isn’t even close to having a sufficiently expansionary monetary policy. It’s latest inflation figures are below 1%, significantly undershooting its stated goal of 2%: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/japan-inflation-slows-in-october-2014-11-27-194851155?dist=lbeforebell

28. November 2014 at 00:56

Sorry, still can’t see it. I will just assume it’s there.

28. November 2014 at 01:28

Keynesianism and Austrianism both rely on the gut feeling that money is something valuable by itself, whose scarcity cannot be overcome (think “gold standard”).

Of course, fiat money means this is no longer true. But the very limited computing power of the human brain has yet to catch up with this.

28. November 2014 at 05:09

I bet gardening is more rewarding than this.

28. November 2014 at 05:23

Thanks Travis, I added an update.

Martin-2, I doesn’t show any of those things. It shows that as G/GDP rises, G/GDP rises.

Andy, No, Japan is not a counterexample. A few posts back I explained that even with monetary offset you’d expect a sharp fall-off in growth after a sales tax increase. If the hit to growth was permanent (still to be determined) then I’d be worried.

28. November 2014 at 05:57

The interesting thing about Tyler’s fifteen (which unfortunately needed to be there): it points to how this argument can be made in the first place. In spite of the horrible deficiencies in their approach, government still makes a miniscule amount of payments into a service marketplace which – because of the way it is structured – is not met well on privately based terms. The lack of structural efficiency on the part of private interests is what allows this particular aspect of a Keynesian argument.

28. November 2014 at 06:06

Scott Sumner,

If the fall in Japanese RGDP was due to an adverse shift in the RGDP/inflation split (as it seems to be from what I can quickly find on FRED) then this might be evidence for some non-AD explanations of the Japanese malaise (were it not for the sales tax increase) but I can’t see how it could be evidence for Keynesianism.

28. November 2014 at 07:03

I’m thankful for Edward’s joke of an article. It actually made me chuckle.

28. November 2014 at 07:12

Agree with rob that anytime somebody claims war is good for an economy it’s time to tune them out.

…

Also, there is a classic short-term/long-term misunderstanding in the data. Deficit spending leads to short-term grown, long-term problems.

Rising deficit spending of all kinds (government, consumer, real estate) put more spending in the economy in the 00’s before the bill came due.

Then we have a period austerity and deleveraging and people blame the austerity on the austerity! It’s like saying a hangover is caused when you stop drinking.

28. November 2014 at 08:51

Speaking of government spending, have you seen the new FT article which claims the Chinese gov’t has wasted $6.8 trillion in investments?

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/002a1978-7629-11e4-9761-00144feabdc0.html?siteedition=uk#axzz3KJ2ntEte

The FT pins it down to ultra-loose monetary policy, but I was wondering if you’d personally dispute that? Inflation (as of July ’14) was running at about 2.3pc, but inflation, of course, isn’t as good as other economic aggregates for judging the state of monetary policy. However, the PBC’s rate is currently 6pc which, if I’m judging it correctly, points away from past monetary tightness.

Anything to say?

28. November 2014 at 09:12

Here’s a graph on deficit spending and GDP growth, 2007 to 2013.

There is no correlation.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/28/deficit-spending-and-gdp-growth

28. November 2014 at 09:27

Next recession we should forget about stimulus spending and start bombing our cities. We now have proof this will make us all richer; because nothing increases our wealth more than destroying our assets.

28. November 2014 at 09:32

Jens Weidmann Tells Conference: To Believe Monetary Policy Can Create Lasting Jobs Is an Illusion

http://online.wsj.com/articles/bundesbanks-weidmann-rejects-calls-for-german-stimulus-plan-1417177202

28. November 2014 at 10:30

‘Agree with rob that anytime somebody claims war is good for an economy it’s time to tune them out.’

Which would include Thomas Piketty, since he made exactly that claim to Russ Roberts in his recent EconTalk podcast.

28. November 2014 at 10:36

This from UCLA’s Sebastian Edwards is about foreign aid, but it works pretty well for all economic dynamics (including the Klein-Edwards argument);

http://www.voxeu.org/article/development-and-foreign-aid-historical-perspective

‘I argue that international aid affects recipient economies in extremely complex ways and through multiple and changing channels. Moreover, this is a two-way relationship – aid agencies influence policies, and the reality in the recipient country affects the actions of aid agencies. This relationship is so intricate and time-dependent that it is not amenable to being captured by cross-country or panel regressions; in fact, even sophisticated specifications with multiple breakpoints and nonlinearities are unlikely to explain the inner workings of the aid-performance connection.

‘Bourguignon and Sundberg (2007) have pointed out that there is a need to go beyond econometrics, and to break open the ‘black box’ of development aid. I would go even further, and argue that we need to realise that there is a multiplicity of black boxes. Or, to put it differently, that the black box is highly elastic and keeps changing through time. Breaking these boxes open and understanding why aid works some times and not others, and why some projects are successful while other are disasters, requires analysing in great detail specific country episodes. If we want to truly understand the convoluted ways in which official aid affects different economic outcomes, we need to plunge into archives, analyse data in detail, carefully look for counterfactuals, understand the temperament of the major players, and take into account historical circumstances. This is a difficult subject that requires detective-like work.’

To which I’ll add that there’s no guarantee that that detective work will succeed.

28. November 2014 at 10:55

W. Peden, Agreed, but even if NGDP did fall it wouldn’t really provide any evidence for the Keynesian model, as shoppers would time their purchases to avoid the tax, while not changing their long run demand.

Ashton, If true, monetary policy has nothing to do with it. The problem is credit policy.

However the FT says it got the number from a study that essentially pulls the number out of thin air. There’s no solid evidence to support the claim. Free Exchange has a post criticizing the study.

28. November 2014 at 11:29

Thank you for the link to Tyler Cowen. I note that after point 15 Cowen (in his conclusion) says “And it would be wrong to conclude that Keynes was anything other than a great, brilliant economist.” 🙂

28. November 2014 at 11:44

And think- just the next day Scott Sumner declares “Finally! Proof that the Keynesian model is true”. I guess Keynes really is winning…

28. November 2014 at 11:47

Daniel:

“Keynesianism and Austrianism both rely on the gut feeling that money is something valuable by itself, whose scarcity cannot be overcome (think “gold standard”).”

“Of course, fiat money means this is no longer true. But the very limited computing power of the human brain has yet to catch up with this.”

We can always count on you to lay eggs on this blog.

Fiat money does not abolish scarcity of money. Scarcity as defined by Austrians is an economic category. It means that whatever is called scarce is an object of economic action, and catallactically this means it is priced.

The last time I checked, all fiat currencies are objects of economic action, and are priced.

Money is scarce. If a commodity were not scarce, it would not be a money.

You have a childish understanding of what scarcity means. It does not mean a measurable quantity that is below some standard. It does not mean a person in a desert saying “Boy is water sure scarce here!”. Scarcity as an economic concept means that subjective wants for a commodity exceeds its supply. This is always true for priced objects. It is why they have a price. A buys something from B for a price because that something is not in an unlimited supply whereby individuals do not need to buy it from anyone else. Think sunlight.

When Austrians say money is scarce, they aren’t making a normative statement that money ought to increase in supply. They are making a factual statement of what money is.

Statements like “fiat money has abolished scarcity of money” are statements that prove you’re economically illiterate.

28. November 2014 at 12:02

Major Freedom- fiat money, by definition, is not scarce to the government who issues it. I believe that was Daniel’s point.

28. November 2014 at 12:37

Jerry, Yes, Keynes made great contributions to economics.

But Keynesian economics was not one of them.

28. November 2014 at 17:27

“Martin-2, I doesn’t show any of those things. It shows that as G/GDP rises, G/GDP rises.

Andy, No, Japan is not a counterexample. A few posts back I explained that even with monetary offset you’d expect a sharp fall-off in growth after a sales tax increase. If the hit to growth was permanent (still to be determined) then I’d be worried.”

isn’t that a tautology ?

what exactly is the point >? It is clear that it is obvious to you, but it is far from obvious to me

29. November 2014 at 07:18

Patrick, Edwards was in my class at Chicago–he’s a very good economist.

Ezra, The post is a joke.

29. November 2014 at 11:37

Scott, I’m not sure how in

Y → Y + δG + (∂C/∂G) δG + (∂I/∂G) δG + (∂NX/∂G) δG

The assumption

(1) |∂C/∂G| , |∂I/∂G| , |∂NX/∂G| ~ 1

is more “obvious” or “natural” than

(2) |∂C/∂G| , |∂I/∂G| , |∂NX/∂G| << 1

such as to be the object of ridicule. Actually the simpler linear theory (2) seems like it should be the starting point rather than the needlessly complex (1) … especially given that macroeconomic data is fairly uninformative so doesn't actually distinguish between the two theories.

Another way, theory (2) has one parameter while theory (1) has four and there are only about 200 quality data points (quarterly GDP numbers) for the US. Additionally, I am fairly sure theory (1) makes the case that those four parameters are actually functions that can change (Lucas critique). That means theory (1)'s explanatory power is hard to distinguish from a just-so story.

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2014/07/beware-implicit-modeling.html

29. November 2014 at 12:04

Jason, You are reading waaaaaaay too much into this post. My post has nothing to do with any of the ideas in your comment. Reread the Edwards post. I’m not ridiculing anyone’s theories.

29. November 2014 at 21:59

Jerry Brown:

“Major Freedom- fiat money, by definition, is not scarce to the government who issues it. I believe that was Daniel’s point.”

I know that was his point. That point is wrong. Fiat money is not by definition not scarce to the government who prints it. Scarcity is ubiquitous. Fiat money does not abolish money scarcity. Fiat money is priced precisely because it is scarce. If a fiat currency really made money no longer scarce, then that currency would not and could not be a tool of economic calculation. That currency would cease being an object of human action. It would cease being a money.

No matter how much fiat money a state prints, it will be in a finite supply, and it will be rivalrous, up to the point of outright currency rejection/collapse.

30. November 2014 at 02:56

When reality insists on contradicting you, the logical thing to do is to define reality away.

30. November 2014 at 18:25

Major Freedom, why should I read any of your comments at this point? A fiat currency is totally “un-scarce” to the entity that issues it. You know that, why argue the point. You may think that it would be better if it was “scarce”, but that just is not the case with a fiat currency.

20. December 2014 at 11:32

[…] “seems to show that government has a pretty straightforward effect on GDP.” But as Scott Sumner pointed out in amusement when he saw the article, the chart does nothing of the […]