We’ve been in a market monetarist world all along, but recent events have made that quite obvious. I’d like to explain why in a slightly roundabout fashion.

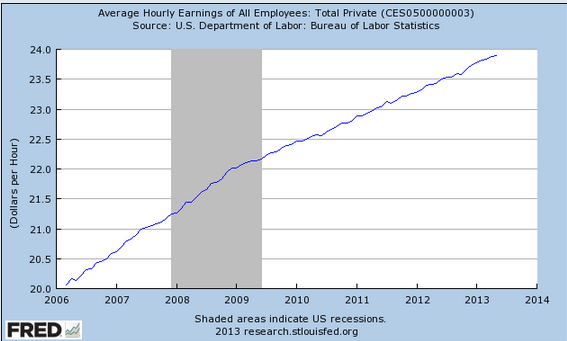

Skeptics like George Selgin have occasionally asked why I think monetary stimulus is still needed. After all, NGDP has been growing at about 4% rate for nearly 4 years, and you’d think wages and prices would have adjusted by now.

There are actually two different ways of thinking about this question:

1. Figure out what is the optimal monetary regime, and then judge current Fed policy against that benchmark.

2. Consider the Fed’s own announced goals, and then judge current policy against those goals.

I don’t have strong views on the optimal monetary regime. I could see good arguments for a 3% growth NGDPLT regime, or a 5% growth NGDPLT regime. And I can see good arguments for starting the clock in 2008 or 2013, or something in between. If we started the clock in 2013, then a 3% NGDPLT regime would call for tighter money right now, and a 5% NGDP regime would call for easier money.

But in some ways it makes more sense to judge policy against the Fed’s own announced goals. You might wonder why, given the Fed often fails to hit those goals. The reason is that from 1983 to 2008 the Fed actually did a pretty good job of addressing its dual mandate. And in the future they may also do a pretty good job. That suggests that adhering to the mandate right now would reduce uncertainty and macroeconomic instability. It does no good to tell the Fed to aim for zero inflation, or negative 1%, or positive 6%, if they will soon be aiming for 2% again. We need stability, predictability.

So that raises the question of why they have recently failed, or indeed if they have recently failed.

And that’s where the recent success of market monetarism comes in. For 4 years we’ve been battling on two fronts; trying to convince the profession that faster NGDP growth was needed, and trying to convince the profession that the Fed could deliver faster NGDP growth—indeed that the Fed was continuing to steer the economy at the zero rate bound.

And suddenly in the last few weeks it’s as if everything has become clear. As if we’ve driven out of a dense fog into a sunny uplands, where the air is transparent. Here’s the first sentence of a typical recent story:

The Federal Reserve almost entirely drove the markets this week.

Yes, and that doesn’t happen when an economy is in a liquidity trap. But the bigger story was elsewhere.

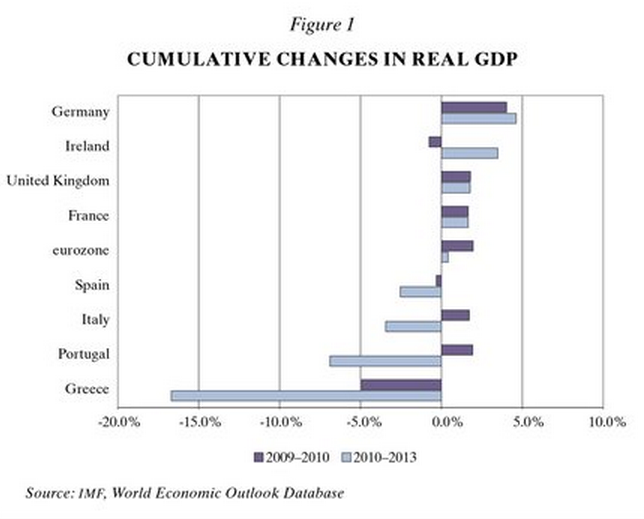

Let’s start with the question of why we’ve done so poorly since 2008 if the Fed was following the same mandate (stable employment and roughly 2% inflation) as in 1983-2008. Why is that policy not producing the good results of 1983-2008? If there was any doubt as to the answer to that question, it’s been definitively dispelled by Bernanke’s recent press conference. We aren’t getting good results precisely because the Fed is not acting in such a way as to implement their mandate. Inflation is well under 2%, and likely to stay low, and the unemployment rate is far above the Fed’s estimate of full employment. That means the Fed should further ease policy, and yet Bernanke just announced that they are likely to tighten policy, even if the economy continues along its current path. During 1983-2008 they consistently adjusted their instruments in such a way as to hit their mandate. Now they don’t. They are failing because they’ve enacted the exact same policy mistakes that Ben Bernanke criticized the BoJ for making in earlier years.

The Fed has us just where they want us to be, and will adjust policy to keep us on the current path. There were fears (even within the Fed) that monetary policy would be unable to offset the effects of fiscal stimulus. Bernanke has recently dispelled those fears:

Bernanke said the quantitative-easing program could end in the middle of next year. The chairman was upbeat about the outlook, saying housing was strong and the recovery seemed to be brushing aside any headwinds from fiscal policy.

This is what a market monetarist world looks like. The Fed is steering the nominal economy, bad outcomes (for AD) are due to bad Fed policy, and fiscal policy is ineffectual. One of two things will happen over the next few decades:

1. The Fed will keep NGDP growth fairly stable.

2. The Fed will allow erratic fluctuations in NGDP growth.

In case one the market monetarists win.

In case two the market monetarists also win. High NGDP growth will lead to excessive inflation, and we can say; “I told you so.” A sharp fall in NGDP growth will lead to recession, and we can say; “I told you so.”

Unlike in 2008, the whole world is now watching NGDP. No more excuses. (OK, the whole world isn’t watching yet, but Michael Woodford is.)

From a purely selfish perspective, case one is actually the worst case. If NGDP growth is stable then macro as we conceive it today (which is mostly a demand-side field) will disappear, and that means market monetarism will disappear. Even worse, the residual problems (and there will be supply-side problems) will appear to be failures of market monetarism. And we won’t have any useful advice to offer, other than “Money won’t solve that problem, nor will demand-side fiscal stimulus.”

Why is the Fed adopting policies likely to cause it to fail? I don’t know. Commenter “James of London” links to people who spot the sinister influence of Jeremy Stein, who thinks the Fed should consider adding a third policy goal, financial market stability. That might mean raising rates or ending QE even if other indicators suggest more stimulus is needed. Who appointed this conservative to the Fed? The same President who appointed 5 of the other 6 board members. The President that supposedly thinks the economy needs more AD. Thank God for regional Fed presidents like Bullard, Dudley, Evans, Rosengren, Kocherlakota, Williams, etc.

And where is Brad DeLong’s vitriolic ridicule when we need it most?

And sometimes the people are smarter than I am and done their homework. Then I have a very hard task indeed–and readers should understand that for them to bet on the correctness of my conclusions would not be to maximize expected value. Jeremy Stein is such a case.

As I understand Jeremy Stein’s view, it goes more or less like this:

[DeLong then presents Stein’s argument] . . .

It is Stein’s judgment that right now whatever benefits are being provided to employment and production by the Federal Reserve’s super-sub-normal interest rate policy and aggressive quantitative easing are outweighed by the risks being run by banks that are reaching for yield.

I do not know why this is Stein’s judgment. I do not know how I would go about making such a judgment.

Perhaps DeLong is saving up his insults for stupid conservatives that worry about bubbles and hence oppose monetary stimulus. Conservatives that don’t teach at Harvard. (Sorry if this is too snarky, the angel in my other ear is telling me I should praise DeLong for being civil. And DeLong is smarter than he seems to think, certainly smarter than me.)

Even more amusing is that the same day Obama picked Stein he also nominated a former GOP administration official, to provide “balance” in order to get the two picks through the Senate. And who is the blogger that has been talking about President Obama’s incompetence on monetary policy ever since 2009?

PS. In the comment section there was lots of discussion of why real interest rates have recently risen sharply. I find this issue to be really puzzling, but I think some people may have failed to pick up on the fact that I’ve always found this issue to be mystifying. Consider that some of the previous US QE announcements seemed to lower bond yields, but later on bond yields rose during the actual QE program, as the economic outlook improved. Or consider that the recent Japanese QE announcement seemed to initially lower bond yields, but then they rose sharply as the program raised inflation expectations. Indeed you now have the following conventional wisdom:

1. Japanese QE is raising inflation fears and raising bond yields.

2. Fear of an end to US QE is raising bond yields.

Can both be right? Do you see why I find this confusing? Then add in the fact that some of the increase in US yields did occur after news of stronger than expected economic growth, but not all. Some occurred after more contractionary than expected monetary policy announcements.

Some market monetarists are less enamored with the EMH than I am, and this sort of situation certainly works in their favor. They can claim that the fall in bond prices is a due to a market failure, as investors don’t yet see that the tight money policy will slow growth, and eventually lead to lower bond yields. Maybe, but then why call it “market” monetarism?

Of course if we had a NGDP futures market then all of these puzzles would be easily resolved. No more mystery. No need to speculate as to the possible existence of positive supply-shocks, etc. But we aren’t willing to spend a few $100,000 on a prediction market that would vastly improve our knowledge base, our ability to conduct effective monetary policies. And that’s the real mystery.