No apology needed

Tyler Cowen has a new post on “The Chinese Credit Crunch.” At one point he makes this off-hand comment:

This economy was addicted to cheap credit in the first place, so that’s a big deal. (By the way, promising to print more currency won’t solve the core problem here, with apologies to Scott Sumner.)

This is a bit puzzling, as I doubt in the entire blogosphere there’s a stronger opponent of mixing monetary policy and credit policy than me. Just a few days ago I did a post entitled “Please, keep finance out of macro.”

Not only do I oppose using monetary policy to solve the “core problem” in China, but I oppose using it to solve ANY problems, anywhere. Monetary policy should be neutral, aimed simply at avoiding the creation of problems, such as unstable NGDP growth.

I’d guess that Tyler Cowen and I have pretty similar views on what China’s core problems are, and they aren’t anything that can be fixed with monetary policy. Fortunately the new government seems committed to accelerating economic reforms.

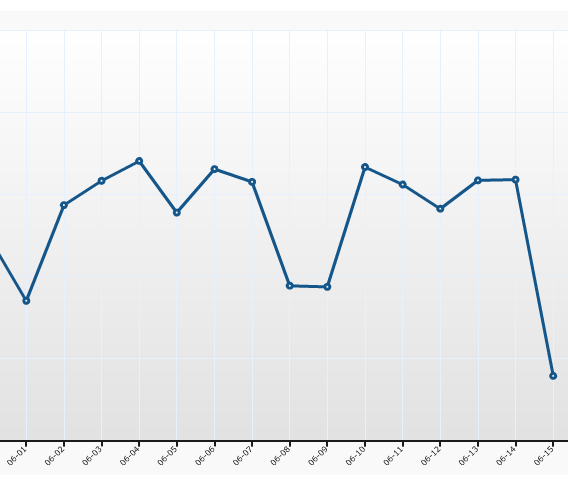

Now suppose I’m wrong, and Tyler wasn’t referring to the credit crunch as the core problem in China, but rather insufficient NGDP growth. Then he would be wrong. Tyler has (correctly) argued on numerous occasions that the US isn’t stuck in a liquidity trap, and obviously that’s even more true of China. I don’t know the current Chinese NGDP growth rate (I believe it’s close to 10%) but if it was slowing faster than desirable (as Lars Christensen suggests may be occurring) it would not represent a problem that monetary policy could not solve. Obviously with “money printing” the PBoC could speed up NGDP growth to 100% or 1000% if it so desired. In any case, I think it’s pretty clear Tyler is referring to the credit crunch, not low NGDP–and on that issue I entirely agree.

I haven’t followed the Chinese situation very closely, but I’d guess that monetary policy failures (if they exist) constitute less than 2% of China’s problems, the rest are structural.

PS. Commenters: Don’t say; “Monetary policy and credit policy in China are linked.” I doubt it. Don’t confuse nominal policies with real policies. But even if true it would have no bearing on my argument. I’d simply recommend de-linking them.