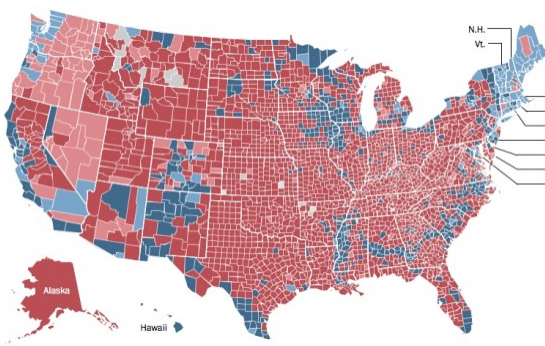

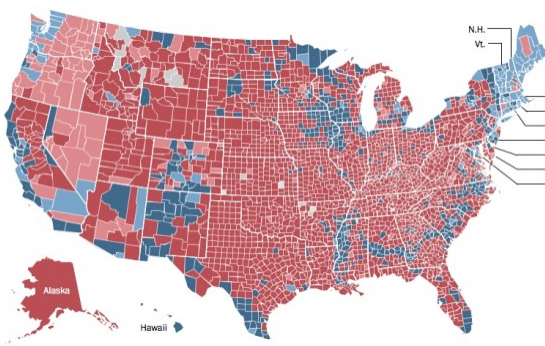

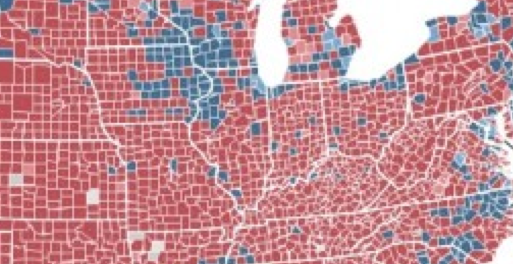

Almost everyone finds mysteries interesting. Almost everyone thinks the American Midwest is boring. But what if there was an interesting mystery in the American Midwest? Take a look at this election map showing the winner by county. (America has about 3000 counties.)

What do you see?

At first glance you see that Romney won most of the land area, because he won the rural areas. But take a closer look.

Now you see there are a few rural areas that he didn’t win; New England, the band of counties from North Carolina to Mississippi with large black populations, the Hispanic counties on the Tex-Mex border, the iron range of northern Minnesota, Native American counties out west, and some Colorado ski resort areas. But basically Romney won the rural areas. Except . . .

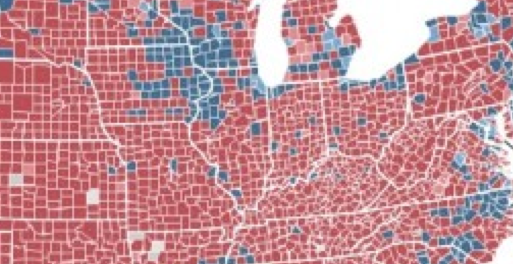

Do you see it now, or do I have to re-enact that famous scene from “Blow Up” (the first art movie I ever saw, and the scene I’m referring to absolutely blew my mind as a young teenager.) Let me help you with a close up:

Do you see it now? There’s a big blob of counties where Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Illinois come together, which are solid blue. Why is that? These are counties with farms and small towns, there are basically no cities of any size. The biggest city is Madison, population 200,000, which is the big blue county in south central Wisconsin, on the eastern edge of the blob. I grew up in Madison, but I don’t have a clue as to why those counties further west are blue. I always assumed western Wisconsin was exactly like north-central and eastern Wisconsin—full of corn and dairy farms, and small towns with one church and 4 bars. Counties full of people with northern European backgrounds. Everywhere else in the Midwest the farm areas went for the GOP, except that strange blob that overlays parts of 4 states. A few of those counties may have small cities with a few manufacturing firms, but look how uniform that blue area is. There is obviously some difference that explains this, and now I feel like we should have been taught in school that southwestern Wisconsin is really weird.

Or perhaps we were taught in school, and I wasn’t paying enough attention. There is in fact something weird about southwestern Wisconsin. The glacier that covered North America during the Ice Age missed this area; indeed it went completely around it, leaving it hillier than normal for the Midwest. It’s called the “Driftless Area.” If you grew up on the coasts you’ve never heard of this area, because nobody on either coast finds the American Midwest to be at all interesting. They rather go visit Paris or Bali.

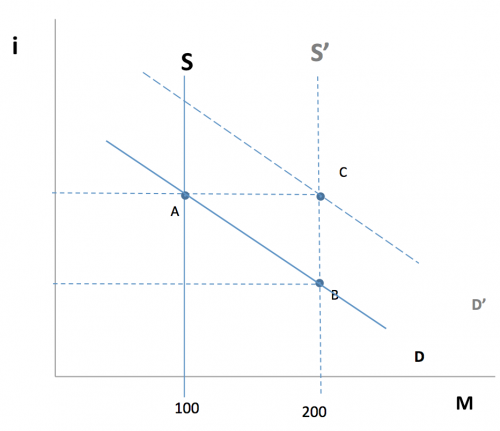

So here’s a map of the Driftless area:

Whoa! That is exactly the same area as the strange blue blob of rural Obama voters. This is beginning to resemble a Stephen King novel, or H.P. Lovecraft. What’s going on in them thar hills? You might argue the blue extends a bit further south into Illinois, but that’s probably the Quad cities area, which is somewhat more industrialized. The mysterious blue farm counties almost perfectly match the Driftless Area.

If these counties were red like “normal” rural counties are supposed to be, the race would have been closer. Indeed if the national vote had gone 3% more toward Romney, then those counties might have been the difference that kept Iowa and Wisconsin blue. I wish that had happened. Suppose Romney had won Ohio, Virginia and Florida, but still lost the election because he was one state short. And he would have come close in Iowa and Wisconsin, but not close enough. Obama would have been elected President because a bunch of white farmers in the Driftless Area voted for a liberal black Democrat, while just about all the other white farm counties in American were going for Romney. It was Obama’s ace in the hole had the election been closer.

Why did farmers who settled hilly areas become more liberal than farmers who settled flat parts of eastern Wisconsin? I have no idea. The Appalachian and Ozark regions are far hillier than the Driftless Area, but are strongly red. It’s a mystery. Only God (or Nate Silver) knows the answer.

PS. When I was young I used to skip out of high school and bicycle out to the Driftless Area on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. It was one of those “open campus” high schools, and I hated school. Now you know why my grammar is so poor.

PPS. The Straight Story (a hugely underrated David Lynch film), involved an old guy travelling from northeastern Iowa to southwestern Wisconsin. When you New Yorkers watch the film, think about the fact that that is OBAMA COUNTRY that he’s travelling through—and start reconsidering you prejudices about the rest of America.

PPPS. The old guy reminded me of my dad.

PPPPS. Since we are travelling back to my home state, take a peak at this picture of a huge dragon that my brother and his girlfriend built out of concrete right outside his “house” (which is a converted 1918 auto dealership in rural Wisconsin.)

If you enjoyed this post please support the economy of small town Wisconsin by buying some inexpensive homemade earrings for yourself, or your wife/girlfriend/daughter/niece, etc. At this website. Produced by the artist who designed the dragon.

Don’t be a free-loader.