It doesn’t matter where the money is injected

Ramesh Ponnuru sent me the following article from the Richmond Fed:

“I feel like a lazy bum,” lamented economics blogger Scott Sumner in a recent post. “This morning Ben Bernanke created $250,000,000,000 in new wealth before I’d even finished breakfast.” The Bentley University professor argued that the Fed chairman’s speech that morning had led to about a half percent increase in stock prices worldwide based on the hopes it created for further monetary easing. With it came a windfall for equity investors.

When the Fed injects money into the economy, the effects are not spread evenly. The first point of impact is the banking system, where the Fed trades newly created money for assets. The infusion of cash causes financial institutions to bid down lending rates, which pushes down other lending rates in the economy and, the Fed hopes, stimulates the economy as a whole.

This is technically correct, but it creates a misleading impression. I notice that many commenters believe it matters where the money is injected. Not true. If the Fed injected the money into the computer software industry by buying T-bonds from Microsoft, the impact would be essentially identical. Microsoft would probably take the cash and deposit it in the bank the same day. But even if they didn’t, even if they spent the money on stocks, the impact on interest rates would be identical.

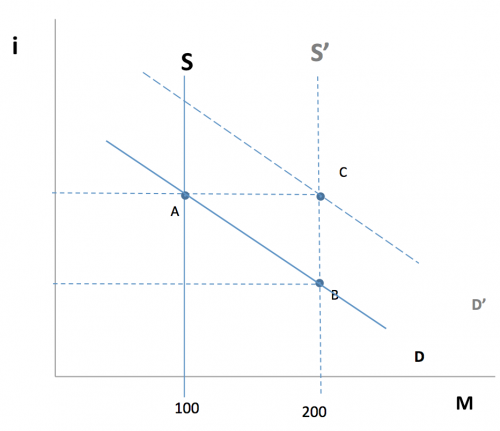

Even before the Fed existed, easy money would often depress short terms rates. For instance, a sudden discovery of gold would depress interest rates under the gold standard. This is because monetary policy has nothing to do with credit, it’s all about changes in the stock of the medium of account (MOA.) When you increase the stock of MOA then prices should increase in proportion. But because prices are sticky in the short run, people temporarily hold excess cash balances (or excess gold balances under the gold standard.) Since the nominal interest rate on the MOA is zero, the nominal interest rate on financial investments is the opportunity cost of holding the MOA. That rate must fall until people are willing to hold those excess cash (or gold) balances. This is shown at point B on the graph below. Then prices and NGDP adjust in the long run, and you go to point C:

Tags:

9. November 2012 at 09:13

And as I’ve been trying to explain to Scott, that diagram is a diagram of stocks. What the Richmond Fed is talking about is the flow effect on interest rates, as the Fed steps up the purchase of one kind of security or another. Even Milton Friedman distinguished between stock and flow effects on interest rates. But I agree that the stock effect (on interest rates) is here much more significant than the flow effect, so people are misguided in complaining about Cantillon effects.

9. November 2012 at 09:27

Of course it matters, people have different marginal propensities to spend, the banks have effectively zero propensity to spend or loan currently, so buying bonds from them does absolutely NOTHING.

9. November 2012 at 09:38

The main problem is that you cannot model banks as people, most people have use for extra cash balances, even if it is only in the long run, most banks do not, mainly because they can easily get money from other banks or the fed anyway if they need it.

9. November 2012 at 09:38

Scott now that you are a world-famous blogger with flattering articles in Business Week, can you tell Bernanke to do QE4 by buying my house for $800 million? It won’t matter, I just think it would be funny.

9. November 2012 at 09:50

And I do not see how this would be compelling to any of the critics, the whole point of the critique is that the system has changed significantly since the gold standard, back then money really was effectively exogenous, but now money is clearly endogenous; thus the idea of a stable MOA is not meaningful, the banking system does not need to worry about aggregate cash balances.

9. November 2012 at 09:55

The Fed buys 250 billion in T-Bonds from a variety of banks — how has the money supply changed? It hasn’t! It is exactly the same. Bank reserves have increased, but until they do something whith those reserves the Feds open market operations have done nothing to the money supply.

When the bank makes loans the banks create money. Money has everything to do with credit.

The Fed cannot create money without banks (short of actually printing more currency). They could buy bonds from MSFT, but without MSFT putting that money in a bank, and the bank using that deposit to make loans, again no money has been created.

“The infusion of cash causes financial institutions to bid down lending rates, which pushes down other lending rates in the economy and, the Fed hopes, stimulates the economy as a whole.”

If this is the way the Fed thinks — and I believe it is — we are not getting out of this slump quickly. Low rates do not stimulate the economy. More precisely low long-term rates, mortgage rates, and corporate bond rates do not stimulate borrowing. A high differential between the banks funding rates and their lending rates stimulates lending!

9. November 2012 at 10:00

“If this is the way the Fed thinks “” and I believe it is “” we are not getting out of this slump quickly. Low rates do not stimulate the economy. More precisely low long-term rates, mortgage rates, and corporate bond rates do not stimulate borrowing. A high differential between the banks funding rates and their lending rates stimulates lending!”

You are looking at two different things here, of course low rates stimulate borrowing, in the sense that plenty of marginal borrowers would not borrow if rates were higher, or would borrow less, or would spend less to make up for the higher interest rates. What you mean is that low rates do not stimulate LENDING, but you have got causality in reverse, the “lending rates” that get bid down here is actually the bank funding rates, and as these rates get bid down, so do lending rates as the spread is higher, which provides more headroom.

9. November 2012 at 10:01

I understand you to say that where the Fed injects money does not matter with respect to interest rates and the broader economy. But does it matter with respect to, in your example, Microsoft? Will it benefit Microsoft if the Fed decides to start buying their bonds instead of MBS and Treasuries? I think there is a widespread perception that issuers or owners of whatever asset the Fed buys benefit disproportionally from QE. If you disagree (or even if you don’t), I would love to read your thoughts on this issue.

9. November 2012 at 10:04

Andrew, Why would it help Microsoft, if they sold it for the exact same price they could sell it in the NY bond market to a private buyer?

9. November 2012 at 10:22

I expect it depends a lot on the cross-elasticities of supply and demand. If all assets and goods were perfect substitutes in demand or supply, it wouldn’t matter what the Fed bought.

Take a very extreme case. Suppose the Fed doubled the monetary base, bought houses rather than government bonds, and rented out the houses. The Cantillon effects of that very extreme case would still be zero if the Fed simply displaced private landlords who thought that holding houses and bonds were perfect substitutes, and if tenants thought that having the Fed as a landlord were no different from a private landlord.

Hmmm. Maybe the Fed should buy Bob’s house?

9. November 2012 at 10:29

Are you saying it wouldn’t matter if the fed injected money into the economy by purchasing human skulls from North Korea instead of buying bonds from primary dealers? Is that what that those charts above are proving?

really? it doesn’t matter how it is done?

9. November 2012 at 10:32

microsfot would be selling $40 billion of bonds per month…instead of what they sell now…even if it is at the same price as they sell them now, you would see profund changes somewhere at microsoft. I’m guessing that bonus season in manhattan(primary dealers) wouldn’t be as good either

9. November 2012 at 10:34

“If all assets and goods were perfect substitutes in demand or supply, it wouldn’t matter what the Fed bought.”

Which they obviously are not, which means it.. does matter.

9. November 2012 at 11:02

Doug M.:

The Fed doesn’t only buy bonds from banks. They buy bonds (indirectly) form households and firms other than banks. This directly increases the money holdings of those households and firms. Now, if those households and firms just hold the additional money balances, then there is no effect on spending, though the quantity of money did increase.

9. November 2012 at 11:16

Saturos, I agree that it makes a small different what type of bond is purchased. My point is it makes no difference whether the bond is bought from a bank, and individual, or a company.

BTW, I still plan on addressing your back comments, but I’m running way behind.

Britonomist, You said;

“Of course it matters, people have different marginal propensities to spend, the banks have effectively zero propensity to spend or loan currently, so buying bonds from them does absolutely NOTHING.”

All I can say is “wow”. You aren’t even in the right ballpark.

Nick, You said;

“I expect it depends a lot on the cross-elasticities of supply and demand. If all assets and goods were perfect substitutes in demand or supply, it wouldn’t matter what the Fed bought.”

See my answer to Saturos, this post isn’t about what the Fed buys, it’s about who they buy it from. It makes no difference if they buy a bond from a bank or Microsoft.

I agree that it matters what the Fed bought, althought in practice not very much as T-bonds and MBSs are close substitutes.

Gabe, Only a very slight difference, unless the Fed bought large quantities.

9. November 2012 at 11:47

“All I can say is “wow”. You aren’t even in the right ballpark.”

Why do you say that? Do not say I am unfamiliar with market monetarism, I have been reading yours and Nick’s (and others’) blogs for years, practically since the beginning. I am familiar with your arguments and models, and have even championed them at times, and defended you on these comments sections numerous times. I am strongly familiar with monetarist economics, I have to sit exams on this stuff. I have of course also have been critical of your arguments on the monetary transmission mechanism for quite some time now; why do you think I remain critical after all this time? Am I just an idiot who does not get your arguments, or is there something missing? Why would you not bother to provide any argument this time around?

9. November 2012 at 11:48

Bill Woolsey,

If the Fed buys a bond from me, my ballance sheet is unchanged. Okay, a low risk T-bill has been replaced by lower risk cash, but really, the effect is as close to zero as could be. My spending doesn’t change. In fact, as Prof Sumner points out in annother post today, if the fed drives rates too low, I may be forced to increase my rate of savings (reduce my spending) to meet my needs for future cash. Now assuming I keep my money in the bank rather than under the matress, the bank’s ballance sheet does change. Once again, banks create money. Open market operations create bank reserves which can be lent, and that is how money is created.

Britonomist,

Ultimately the borrower and the lender are running the same calculus. Is the potential return of this investment sufficiently greater than than my cost of capital to be worth the risk. Both borrower and lender have to be able to answer this question. The Fed funds rate sets the cost of capital for the bank, and the long-term / mortgage / corporate rates set the return for the bank and the cost for the borrower.

So, is the problem an unwillingness to lend or an unwillingness to borrow? Perhaps without hard evidence, I am of the opinion that the banks are being tight even if the Fed is trying to be easy. Higher long-term rates would give the banks incentive to lend.

Now, maybe the problem is no demand to borrow, no good ideas to invest in, or too much risk. In which case, I am not sure what the Fed has the power to do.

9. November 2012 at 11:48

I notice that many commenters believe it matters where the money is injected. Not true.

I agree that it matters what the Fed bought

I think this language is confusing, because some people read (at least I do, so I get confused a lot) “where” and “what” to mean the same thing: financial securities in the financial markets. As I understand the distributional arguments, by choosing to buy T-bills instead of (say) underwater mortgaged homes, the Fed benefits banks and the financial system more than (say) underwater mortgage borrowers.

This gets further confusing (at least for me, I’m not an economist) because some (all?) economists say that if the Fed printed some money and instead of buying assets it were to send it by mail to every household, that counts as fiscal policy, not monetary. Why the difference?

9. November 2012 at 11:54

“So, is the problem an unwillingness to lend or an unwillingness to borrow? Perhaps without hard evidence, I am of the opinion that the banks are being tight even if the Fed is trying to be easy.”

I agree.

” Higher long-term rates would give the banks incentive to lend.”

Not quite, higher long term /spreads/ give the banks incentive, which the fed can help by lowering the cost of capital. In normal times this can help a lot, so it makes sense to say the central bank lowering interest rates help.

However I agree that right now the cost of capital cannot be lowered any more, so it makes little sense to think additional QE will impact loan creation, which means it makes little sense to think QE will impact anything at all, other than slightly lowering longer term interest rates.

9. November 2012 at 12:05

“Now, if those households and firms just hold the additional money balances, then there is no effect on spending, though the quantity of money did increase.”

Money for households is bank accounts, which are created and destroyed as needed. Fed purchases don’t force households to hold more money. They only force banks to hold more reserves.

9. November 2012 at 12:24

If the counterpart of an OMO is not relevant, doesn’t that mean that debt monetization (if T-Bills are bought from the Treasury at market price) is equivalent to an OMO?

9. November 2012 at 13:42

Doug M:

The Fed buys 250 billion in T-Bonds from a variety of banks “” how has the money supply changed? It hasn’t! It is exactly the same. Bank reserves have increased, but until they do something whith those reserves the Feds open market operations have done nothing to the money supply.

Reserves are a part of the aggregate money supply. Just because they aren’t “circulating” at any given point in time, it doesn’t mean it isn’t a part of M. After all, the cash in my wallet is not circulating right now, but it is part of the money supply.

When the Fed purchases T-bonds, it is increasing a component of the money supply. Now, whether or not it will be followed by an increase in the aggregate money supply, depends on what is happening to bank credit.

9. November 2012 at 13:42

Banks could not keep expanding credit unless the Fed kept increasing reserves.

9. November 2012 at 17:19

BTW, if you are talking purely in terms of the impact on interest rates, then I would agree with you, but I gave the impression you were also saying the effect on NGDP is the same, that is a very different statement.

9. November 2012 at 17:19

I got the impression*

9. November 2012 at 18:45

Britonomist, You said;

“Of course it matters, people have different marginal propensities to spend, the banks have effectively zero propensity to spend or loan currently, so buying bonds from them does absolutely NOTHING.”

The MPC might conceivably be relevant if the Fed was dropping money from airplanes, and the people picking it up had more income. But OMOs don’t boost income, they are done at current market prices for the assets being purchased.

If by “spend” you are including asset purchases, then that still doesn’t matter. If I buy a share of stock with the new money, the person selling the stock will put it in the bank. What matters is the total supply of base money, in relation to the total demand–not where it gets injected.

Laurent, I think everyone agrees that debt monetization is an OMO.

10. November 2012 at 04:49

I don’t understand why bond-buying programs would have no effect on the bonds’ prices (maybe simply because this is over my head). If a private buyer announced he would buy $40 billion worth of bonds from Microsoft each month, surely that would drive prices up? And when the ECB announced its plans to buy Greek debt, the announcement affected the market price of Greek bonds. And when the Fed announced QE, that drove the price of Treasury yields up. I recall Prof. Sumner arguing that if QE were effective, it should actually be driving the price of T-Bills down, not up, but it seems obvious that this is not how it has functioned to date. So why would a large-scale Microsoft bond buying program leave prices unchanged?

10. November 2012 at 04:51

(sorry I meant “price of Treasury bonds up” not “price of Treasury yields up”)

10. November 2012 at 04:58

Doug M.

I said that if people just choose to hold the extra money, then there is no spending.

However, if the Fed purchases bonds from a household or firm, then the quantity of money rises.

Your claim that open market operations solely increase the reserves of bank is simply false. You should stop making it.

You can say that changes in the quantity of money have no effect on spending on output if you like, but if the central bank purchases assets from people other than banks, the quantity of money rises.

By the way, money is the medium of exchange and not just an asset that people can choose to hold. If someone sells a bond for money, that does not mean that the person wants to hold money rather than a bond.

10. November 2012 at 05:20

Andrew:

Ceteris paribus, an open market operation raises the price and lowers the yield on the bonds being purchased.

However, there are other effects as well–increased future nominal GDP split up between higher prices and increased output.

These factors raise credit demand and tend to raise interest rates now.

Expectations of those effects can lead more people to sell bonds than the amount the Fed is buying. And so, ceteris is not paribus and open market purchases can result in falling bond prices and higher interest rates of even the particular bonds the Fed is buying.

Lower interest rates motivate firms to purchase more capital goods, but expecations of increased sales of output also motivate firms to purchase more capital goods.

Lower interest rates motivate households to save less and purchase more consumer goods, but expectations of improved future employment opportunties also cause households to save less and purchase more consumer goods.

If expectations of future nominal income are well anchored, then these expecational effects won’t exist.

Market monetarists right now favor increasing those expectations. And so, we see the impact of open market operations on interest rates as ambiguous and really do believe that an expansionary monetary policy now would raise them.

But if our preferred regime was adopted, nominal GDP level targeting, and people always expected nominal GDP to be on target, then the direct effect of open market operations on bond prices and interest rates would likely dominate.

By the way, if the central bank is using interest rates as a policy instrument, then the expecational effects just means that more open market operations are implemented to keep the interest rate on target.

For example, the Fed lowers its target for the interest rate and buys some bonds to get interest rates lower. People expect higher nominal GDP in the future and so sell bonds to finance the purchase of capital and consumer goods. This would tend to cause the interest rate to rise above target, but with interest rate targeting, the central bank just buys more bonds. How many bonds exactly must be purchased to keep the interest rate on target? Well, they just buy as many as needed, right?

And so, all of these effects get combined into the effect of the lower target for the interest rate on spending.

If instead, the Fed increased base money a fixed amount, and bought some bonds, what happens to the price of the bonds and the interest rate on them is ambigous. It could go either way. Nothing prevents other bonds holders from selling more than the Fed is buying, pushing down prices and raising yields.

10. November 2012 at 07:29

By the way, money is the medium of exchange and not just an asset that people can choose to hold. If someone sells a bond for money, that does not mean that the person wants to hold money rather than a bond.

Exactly!!! And Scott still doesn’t get how this is crucial to monetary policy…

10. November 2012 at 07:32

(That comment sets me up for continuing the MoA/MoE debate on this page, if necessary. Sorry guys.)

10. November 2012 at 07:47

Bill Woolsey:

That assumes the initial buyers of the bonds intend to hold them until maturity, and it also assumes that the bonds will actually float in the market until maturity.

In the real world, there can be bond bull runs, in which the initial t-bond investors only buy the bonds for the purposes of flipping them, either to the next investor in the chain (who themselves plan to flip them), or to the central bank (who investors know can print money and is not cash constrained and can pay any price).

In these circumstances, the traditional bond pricing model you are using does not apply. There is no good reason for bond investors to pay a lower price to take into account increased future NGDP, or rather increased future price inflation. Your thinking is outdated, and it is a function of you jealously protecting your NGDP fetish.

10. November 2012 at 09:18

I agree with the post that what the Fed buys is important but not from whom.

As long as everyone has an equal chance to buy and sell the assets that the Fed buys, and it buys them at auction, then it makes no difference who the seller is. I suppose one could argue that primary dealers have a slight advantage, but my understanding is the margins are very small.

Whoever trades his bond in for cash, had to have bought that bond for cash in the past. It is already priced into the asset. It’s like under the gold standard. The guy who sells some gold to the government isn’t the one who benefits, it’s the gold miners. Likewise, it’s not the guy who sells his Treasury bond to the Fed who benefits, it’s the issuer of the bond, the Treasury, or ultimately the taxpayers. And that’s who should benefit.

10. November 2012 at 09:39

Andrew, Private buyers don’t create new money.

Saturos, You quoted Bill and then responded;

“By the way, money is the medium of exchange and not just an asset that people can choose to hold. If someone sells a bond for money, that does not mean that the person wants to hold money rather than a bond.

Exactly!!! And Scott still doesn’t get how this is crucial to monetary policy…”

I’ve been making the HPE argument for 4 years, why do you think I don’t understand it? My only point is that the HPE only drives up prices if “money” is the MOA.

10. November 2012 at 20:45

If someone sells a bond for money, that does not mean that the person wants to hold money rather than a bond.

doesn’t really work for MoA, does it?

11. November 2012 at 06:34

Saturos, When there is an increase in the supply of MOA, it becomes a hot potato at the original price level and level of asset prices.

11. November 2012 at 08:28

The problem is the Cantillon effect. Printing money is a transfer of spending power from those who have the old money to those who get the new money first. When you print money to buy financial assets, those that get the new money first benefits the most while everyone else’s spending power falls.

After all, inflation is a tax. It’s probably the single most cruelest and most regressive tax that there is because the people who get the new money first is usually the banking sector and the wealthy.

That’s my biggest problem with QE in its current form, it’s reducing my spending power and giving it to the banking sector. In a way, it indirectly takes money from the poor to give to the rich.

11. November 2012 at 09:20

“it becomes a hot potato”

You mean people accept the MoA for what they sell even though they don’t want to hold or consume any more MoA?

11. November 2012 at 10:41

ssumner:

My only point is that the HPE only drives up prices if “money” is the MOA.

Prices are manifested when goods are exchanged for other goods. Under this umbrella phenomenon of exchanges, it is possible for some goods to become more marketable and more generally accepted than other goods, because they provide additional uses such as store of value and means of account (economic calculation). These goods become money.

Thus, since one cannot divorce money prices from exchanges against the money commodity, it follows that money as a MoE is on a higher logical hierarchy than money as a MoA. MoA is subsidiary to MoE.

Prices are ratios of exchange.

11. November 2012 at 19:52

MF, you’re right that MoA is what generally becomes MoE. But you’re wrong that “since one cannot divorce money prices from exchanges against the money commodity”, it follows that MoA must require MoE. Not so: exchange and MoA accounting can take place under barter as well. Think of a simple economy with only a handful of goods traded: it’s agreed even by Austrians that calculation problems are not so hard there.

11. November 2012 at 20:26

Saturos:

MF, you’re right that MoA is what generally becomes MoE. But you’re wrong that “since one cannot divorce money prices from exchanges against the money commodity”, it follows that MoA must require MoE. Not so: exchange and MoA accounting can take place under barter as well. Think of a simple economy with only a handful of goods traded: it’s agreed even by Austrians that calculation problems are not so hard there.

1. My actual position is that MoE generally becomes MoA, not vice versa.

2. You already tried to critique my argument by referring to barter before, and I will repeat ow what Imsaid then: The context of my argument is a monetary economy. MoA presupposes a monetary economy, as does MoE.

In an economy with, say, gold as a MoA, sellers in general cannot account for their expenses and revenues in terms of gold unlesa gold is exchanged against those goods expenses and goods revenues.

Please recall that I already rejected the assertion that in barter economies “everything exchanges for everything else”. In barter economies, there are “gaps” in the required path of trades that would enable each seller to account for their own expenses and sales in the MoA by way of deduction. Sellers of shoes for example would not be trading with every other seller, but that is what would be required for you to deduce the gold price of whatever good depends on certain goods to be exchanged for shoes.

In addition, there are also multiple paths, multiple exchange ratios for the same goods, from trade node to trade node. This also makes deduction impossible, because there is no method to distinguish one path from another in a rational way.

Barter sellers cannot use gold as a MoA unless gold is already a MoE, which of course means we’re not actually talking about a bartrer economy. In other words, barter and MoA do not mix.

There is also the incentive problem of why sellers would even account for their expenses and revenues in a MoA that they neither receive nor pay out. I mean, that’s why sellers who neither receive nor pay out clamshells are not using clamshells as a MoA, but rather that which is a MoE, namely dollars. Do you think it’s a coincidence?

12. November 2012 at 04:01

ssumner:

Andrew, Why would it help Microsoft, if they sold it for the exact same price they could sell it in the NY bond market to a private buyer?

But that’s just it. They WON’T sell it for “the exact same price” they could sell it in the bond market.

If Microsoft starts receiving checks from the Fed, then that would raise the value of its debt. When your buyer is a money printer, that adds to the demand for whatever it is you are selling, as compared to if that money printer was not present.

If assets sold with central banking are of the same prices as they would be without central banking, then asset prices would not be rising. Inflation of the money supply would not raise prices as compared to no inflation of the money supply.

If the Fed injected the money into the computer software industry by buying T-bonds from Microsoft, the impact would be essentially identical. Microsoft would probably take the cash and deposit it in the bank the same day. But even if they didn’t, even if they spent the money on stocks, the impact on interest rates would be identical.

If the money enters the capital goods sector, it distorts the capital-consumption structure in favor of the capital sector.

12. November 2012 at 20:49

I don’t understand. The critique of the “it doesn’t matter where the money goes” theory is that it simply isn’t true at the zero lower bound. Short-term interest rates are controlled by the supply of money, but if short-term rates are zero than simply injecting more money won’t necessarily have the same impact.

12. November 2012 at 20:52

I take it back; just read Mr. Sumner’s response to Saturos. Is this controversial? Normally central banks care about whom they purchase bonds from as a matter of financial stability, not monetary policy.

13. November 2012 at 06:58

Suvy, You said;

“The problem is the Cantillon effect. Printing money is a transfer of spending power from those who have the old money to those who get the new money first.”

No it’s not. The Cantillon effect doesn’t really exist. Money creation swaps assets of equal value, it doesn’t create spending power.

13. November 2012 at 07:54

No it’s not. The Cantillon effect doesn’t really exist. Money creation swaps assets of equal value, it doesn’t create spending power.

Money creation does NOT “swap assets of equal value.” The inflation ADDS to the demand side of the demand and supply components of pricing. That’s why prices tend to rise when the money supply rises (with a time lag). It takes time for the money to work its way through the market, from person to person, raising demands and prices in a wave like manner spreading out from the initial inflation point (typically the primary dealers today).

If inflation only entailed a “swap of equal values”, then we should not have seen any price or price level increases since at least 1913 when the Fed was created. But we have, so there isn’t a swap of equal values with inflation.

1. In a money economy, one does not use one’s non-money assets to buy other people’s goods. If I have bonds, but sellers of goods only want money, then I have to acquire money. Thus I have to sell my bonds if I want to buy other people’s goods. I can sell those bonds to two basic party types:

a. The first type is endogenous to the given money supply. These parties are earning money that already exists in the market. If I sold my bonds to this type, then the price that I as receiver of the money can fetch is limited to the demand that exists within the endogenous money supply. Ceteris paribus, my selling of bonds does not consist of an addition to the money supply centered in my bank account, but rather, a transfer of money within the existing money supply from one person’s bank account to my bank account. Thus, the Cantillon Effect is not brought about. Money is merely being transferred from one market actor to another. My spending power is not increased, because I am not able to get a higher price for my bonds, ceteris paribus, than what would result from the endogenous demand. Again, this is because there is no inflation to ADD to the demand component to pricing.

b. The second type is exogenous to the given money supply. These parties create new money that does not already exist in the market. If I sold my bonds to this type, then the price that I as receiver of the money can fetch is now expanded to include the demand from an exogenous money supply. Ceteris paribus, my selling of bonds does not consist of a transfer of money within the existing money supply from one person’s bank account to my bank account, but rather, an addition to the money supply centered in my bank account. Thus, the Cantillon Effect is brought about. Money is being added to the existing supply centered on my bank account. My spending power is increased, because I am able to get a higher price for my bonds, ceteris pariubus, than what would result from the exogenous demand. Again, this is because inflation will ADD a demand component to pricing.

————————————-

2. Even with zero additional money creation, is there no “swap of equal values” in any exchanges. This “equal value” notion is a common mistake, dating all the way back to Aristotle if you can believe it. When A trades away good X, to B who trades away good Y, then goods X and Y are not “equal in value”. There is a difference in valuations. A ranks good Y higher than good X, and B ranks good X higher than good Y. That’s why A and B are each trading away their good for the other’s good. It’s because they each value what they are receiving as higher than what they are giving away. If X and Y were really of equal value, then there would be no reason for either A or B to trade them in the first place.

a. In a barter economy, when you go to a sheep seller, and you trade your one cow for his two sheep, then you do so because you value the two sheep more than the one cow. The sheep seller on the other hand values your one cow more than his two sheep. That’s why you both made the trade. The one cow is not “equal in value” to the two sheep. You rank the sheep higher than the cow, and the sheep seller ranks the cow higher than the sheep.

b. In a money economy, when you go to a sheep seller, and you trade your $500 for his two sheep, then you do so because you value the two sheep more than the $500. The sheep seller on the other hand values your $500 more than his two sheep. That’s why you both made the trade. The $500 is not “equal in value” to the two sheep. You rank the two sheep higher than the $500, and the sheep seller ranks the $500 higher than the two sheep.

————————–

The prices of the treasuries that the Fed buys (when it adds to the money supply) increase from what they would otherwise would have been had there been no inflation from the Fed.

Consider what would happen if the Fed announced tomorrow that it will cease and desist buying bonds indefinitely, and instead start buying shares of the S&P 500.

If you can understand why the prices of treasuries would fall and why the S&P 500 would rise and why your salary would probably remain the same in the short run, then you can understand the Cantillon Effect.

13. November 2012 at 10:20

Bill Woosley,

“Your claim that open market operations solely increase the reserves of bank is simply false. You should stop making it.”

The supply of money = Bank Reserves / reserve ratio.

e.g.

The fed injects $1 million into the banking system via open market operations.

The banks lend it. That money is spend and eventually finds its way back to the bank. The bank sets asside 10% and lends the other 90%. This process repeats.

Money supply = Reserves / reserve ratio.

For every dollar that the fed creates the banks potentially create annother $9. The Fed without the banks has significantly less leverage. And, if the bank lending system is clogged, i.e. banks hold excess reserves, then open market opperations are less effective than they otherwise would be.

“You can say that changes in the quantity of money have no effect on spending on output if you like, but if the central bank purchases assets from people other than banks, the quantity of money rises.”

Quantity of money is relevant. However, without the assistance of banks the Fed has a difficult time increasing the quantity of money.

13. November 2012 at 14:19

“I notice that many commenters believe it matters where the money is injected. Not true. If the Fed injected the money into the computer software industry by buying T-bonds from Microsoft, the impact would be essentially identical..”

It would matter to Microsoft. It would matter to the banks. It would matter to capital markets. What you are really saying is that, so long as interest rates get to the same place, it doesn’t matter to you.

Indeed, from a high enough cloud, everything looks “essentially identical.”

26. November 2012 at 05:41

[…] “It doesn’t matter where the money is injected” (The money illusion) […]