Your mission, should you decide to accept it …

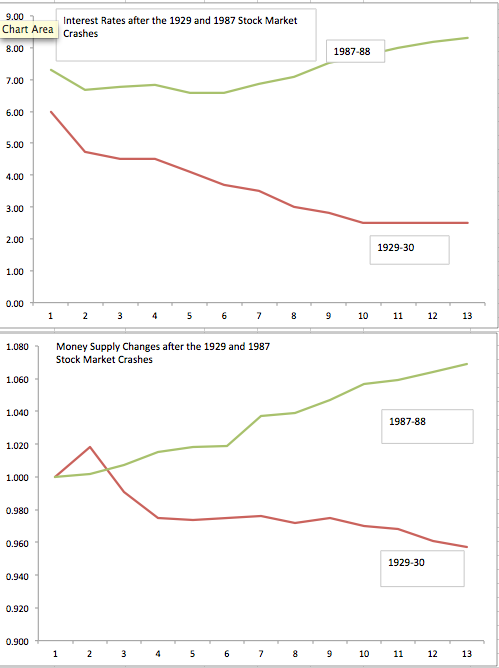

. . . is to compare and contrast the October 1929 and October 1987 stock market crashes. The two crashes were almost identical; and in both cases the market recovered a bit over the next 6 months. The 1929 crash was followed by the Great Depression and the 1987 stock market crash was followed by years of rising RGDP and falling unemployment. You’ve decided to focus on the fact that the Fed was expansionary after the 1987 crash whereas Fed policy was contractionary after the 1929 crash. You are allowed to use only one PowerPoint slide. Which one do you pick to show your audience that the Fed did the “right thing” after the 1987 crash, and the “wrong thing” after the 1929 crash:

In both graphs time=1 is October 1929 and October 1987, whereas time=13 is October 1930 and October 1988. The money supply is the monetary base (indexed to 1.0 in month 1). Which slide would you use to convince your audience that money was too tight after the 1929 crash, but not after the 1987 crash?

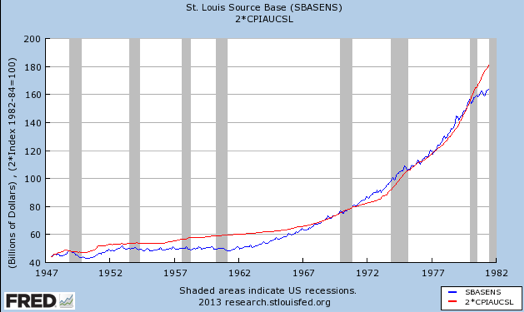

Let’s try another. You’d like to do a PowerPoint presentation explaining the Great Inflation. You are allowed to use only one slide, and you’d like to show how Fed policy became much more expansionary during the 1960s, leading to high and rising inflation from the mid-1960s to 1981. Which slide do you choose?

A triumph for monetarism? Far from it. The monetary base is a lousy indicator of the stance of monetary policy. For instance, the base rose rapidly between October 1930 and March 1933, even as prices and NGDP plunged sharply lower. And we all know it’s been a horrible indicator since October 2008.

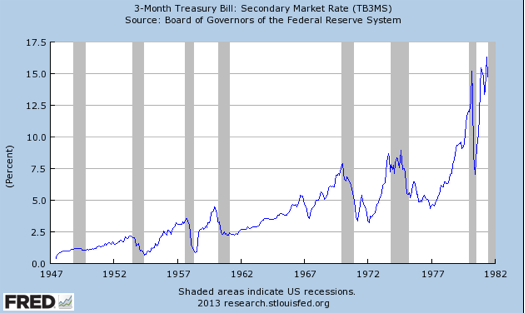

So what’s my point? As bad as the base has been, it’s still a much better indicator than the short term nominal interest rate. Interest rates aren’t just “lousy,” they are flat out horrible indicators. Appallingly bad. Atrocious. Useless. No, less than useless, they offer negative value added. More likely to be wrong than right. If someone put a gun to your head and you had to use interest rates, you’d want to use it as a reverse indicator. You’d be better off assuming low rates meant tight money and high rates meant easy money. That’s how bad it is.

Milton Friedman knew this long ago.

PS. I’ve started work on two projects. One is an online money class, and the other is a book based on my blog. I will start assembling graphs that illustrate market monetarist arguments, and this post is the beginning of that process. I’ll do other posts on occasion as I assemble more graphs. Feel free to provide suggestions, or criticize my posts if you think they are misleading or confusing.

I will occasionally use inflation rather than NGDP, because I am also aiming for something accessible as an intro to money for undergrads.

PPS. Today I was interviewed by both the BBC (radio) and the WaPo. For Chinese readers there is an article on me in iMoney, a HK financial publication. It’s in Chinese.

Tags:

14. March 2013 at 11:44

PS. I’ve started work on two projects. One is an online money class, and the other is a book based on my blog.

Can’t wait. Let me be the first to sign up for the course and pre-order the book.

14. March 2013 at 11:48

Dear Blog Commenters,

Can anyone here read Chinese? If so, could you please find a link to Prof. Sumner’s interview in iMoney (a Hong Kong financial publication)? I’d love to forward it to my Chinese buddy. Thanks.

14. March 2013 at 11:53

In the top graph, I would index graph them on separate y-axis (left side, right side) so you don’t have to take the transformation. I prefer log scale, since that’s how I would look at the data in a regression or cointegration analysis.

That being said, graphs can be misleading sometimes. I tested these two variables (over that period) for cointegration and could not obtain statistically significant evidence of it (with 1 lag).

14. March 2013 at 11:58

Yglesias just wrote this on the “stimulus wars”:

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/03/14/stimulus_the_way_forward.html

” 1. We should aim for a long-term inflation rate of four or even five percent so that the Federal Reserve is much less likely to hit the “zero bound” and lose confidence in its own ability to shape the economy-wide demand picture.

2. We should make specific statutory provision for Fed injection of “helicopter money” into the economy. The metaphysics of fiscal vs monetary policy are less important than the fact that the Fed has the right institutional setup to conduct a joint fiscal-monetary action when needed. A Fed that can order money-financed payroll tax cuts that have zero impact on the deficit is never going to “run out of ammunition” in the war on demand shortfalls.

3. We should beef up automatic stabilizers in the budget by creating some kind of national rainy day fund that automatically releases unrestricted funds to state governments in times of recession. Some elected officials will use the money to avoid pro-cyclical service cuts and furloughs, while others will use it to finance tax cuts and we’ll just live with disagreement about the best way to proceed.”

Question: if we actually did item #1, then wouldn’t items #2 and #3 be unnecessary? Hasn’t Prof. Sumner argued numerous times that there’s effectively no significant difference between the Fed doing “helicopter money” and purchasing U.S. debt?

14. March 2013 at 12:19

Do you really want to start a intro book with a scenario where the central bank responds to an equity market collapse? That sort of suggests that the Fed should target equity market levels, which reinforces many novices’ misconceptions. I realize targeting NGDP might be correlated.

14. March 2013 at 12:38

John Hall, Thanks for the tips on the axes. I’m not a fan of cointegration, and indeed the Quantity Theory of Money does not predict that money and prices are cointegrated, just correlated.

Travis, I sympathize with Yglesias’s frustration, but I don’t think we need to go nearly that far. On the other hand that would probably be much better than recent policy.

14. March 2013 at 12:40

Pemakin, Don’t worry, I won’t suggest that they target equity prices.

My actual goal is to start off by showing how unimportant non-monetary shocks are. Maybe I’ll do a post.

14. March 2013 at 13:02

Scott: ” I’m not a fan of cointegration, and indeed the Quantity Theory of Money does not predict that money and prices are cointegrated, just correlated.”

Careful there.

If the Fed were targeting inflation (or the price level) successfully, like a good thermostat, there should be zero correlation between money and prices.

And if the Fed were targeting NGDP successfully, like a good thermostat, the correlation between money and prices could go either way, depending on the elasticities and the source of the (real) shocks.

Good post BTW.

14. March 2013 at 13:04

I meant: “And if the Fed were targeting NGDP successfully, like a good thermostat, the correlation between money and prices could be positive or negative, depending on the elasticities and the source of the (real) shocks.”

14. March 2013 at 13:06

1- I would have imagined that the fact that high interest rates mean the economy is booming is pretty obvious. CBs are essentially reactive, no matter how ‘ahead of the curve’ they say or think they are.

In recent times, when were the rates the highest? In the mid 2007, if memory serves? When has it been the lowest? About right now…

2- I like Matt ideas, up to a point. I’d rather that the proper fiscal authorities cut the goddam payroll tax and make up for the short fall by taxing the wealthiest 0.01% …

14. March 2013 at 13:13

Nick, Yes, good point. But doesn’t it depend how you define the QTM?

A: We can expect P (or PY) to change roughly in proportion to changes in M.

B: An increase in M will, ceteris paribus, lead to a proportional increase in P, as compared to the level of P that would have occurred had M not increased.

I think you are using the second definition. Which is fine, and in some ways better. But I also think many people see the QT in terms of the first definition.

14. March 2013 at 13:16

Frederic, You’d think it was obvious . . .

14. March 2013 at 13:17

In trying to wrap my head around NGDP targeting and its long term affects, I can’t get past one thing. Doesn’t it get to a point when the private sector cannot take on more debt, and thus needs to deleverage, as what happened post 2008? The only way to keep taking on debt is to have interest rates continue to decline with easier and easier monetary policy. If you read Steve Keen you are familiar with this chart, the blue is total private sector debt. How is that sustainable?

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=eCB

14. March 2013 at 13:17

I remember my own reaction to the 1987 stock market crash very well. I was as scared as I was in the recent crash (even though I didn’t own any stocks back then). I was listening to the all-news radio all day (no internet back then, you young-uns), and reading random stuff on the Great Depression, because I thought it might happen again, and i wanted to experience it as closely as possible.

The book that made the biggest impression on me was “Only yesterday”, by (I think) this guy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Lewis_Allen

14. March 2013 at 13:36

Regarding the great inflation monetary base chart, this is screaming to be put on a log scale.

You are, once again, making me miss M3. The shadow statisticians who continue to calculate M3 show that M3 growth peaked in early ’08, went negative and has been growing at a slow pace since.

The Monetary base, over this same period, exploded in 2009, and again 2011 but has not correlated with growth.

14. March 2013 at 14:35

Scott: As a student of Patinkin (even if only for a few weeks), and of his book (for many more weeks), I confess I always interpret “QT” as B. Yep.

14. March 2013 at 15:19

OK. Having read your response to me in the other thread, I think I was not really be clear. Here is my attempt to be more coherent:

PLT (or NGDPLT) is both a policy goal and – if made explicit, or at least expected by markets – an action towards achieving that policy goal.

So, an explicit policy of 2% PLT is both an accomodative action (in the midst of a crisis where AD is low) and a policy goal.

Looking at it as an action, a means to loosen policy, then it does makes sense to me that Bernanke would surely have undertaken more aggressive accomodation had there been no stimulus. I don’t even think that point is debatable, it’s obvious.

But 2% PLT is not just an action, it’s also a policy goal. That is how I was thinking of it when I read and commented on your post, as a goal rather than an action. And that is the thing I don’t understand: why should being in a crisis without fiscal stimulus have caused Bernanke to adopt a more aggressive GOAL. As I said, I can perfectly understand why it would have caused him to take more aggressive action.

If Bernanke wanted 2% PLT, he should have wanted 2% PLT no matter what the politicians want. Maybe no stimulus would have given him the political cover to adopt such a goal? It’s a very disturbing to think that Bernanke is sitting there even now thinking “We should have a 2% PLT or 5% NDGPLT” – but for whatever reason he is not going to do it.

14. March 2013 at 15:47

Dr. Sumner:

You said:

“The monetary base is a lousy indicator of the stance of monetary policy. For instance, the base rose rapidly between October 1930 and March 1933, even as prices and NGDP plunged sharply lower.”

Suppose someone said this:

“NGDP is a lousy indicator of the stance of monetary policy. For instance, NGDP fell rapidly between October 1930 and March 1933, even as the base rose sharply higher.”

Why is that wrong, but your comment is right? Seems to me that you’re just defining “good indicator” as NGDP, then reasoning that the base is not a good indicator because the base and NGDP went in opposite directions. OK, then why can’t the reverse statement be true?

14. March 2013 at 15:58

One of the things that I always find hard to conceptualise is the relationship between tight money and interest rates. I understand the difference between the liquidity effect on the one hand, and the NGDP effect on the other, but whenever i think of the relationship between money and interest rates, the classic liquidity effect graph pops into my mind, as it has been ground in since undergrad.

I need some “concrete steps”. I know that base growth came to a halt in late 2007. And i know that interest rates fell, and the fed cut rates. I understand that tight money lowers interest rates, and i can visualise that effect for T-bills, but I can’t see that mechanism working for the Fed funds rate through OMOs. I think clearing that up would be good for the textbook, if most undergrads are like me.

A thought; I read somewhere that movements in the fed funds rate often comes from open “mouth”, rather than open market operations. That makes changes in the fed funds rates seem more like managing expectations, rather than actual currency injections. Could that explain why the fed funds rate fell, but the base stopped growing?

14. March 2013 at 16:06

I would like to pre-oder a copy of your book immediately.

14. March 2013 at 18:08

Again, when you talk to people at commercial banks and central banks, they will tell you that the monetary base is endogenous. The private sector lends, borrows and demands cash and the CB has no choice but to supply it at the rate it sets. So yes, the base is a good indicator of what the economy is doing, but it is not something the CB can control. Again, talk to bankers. The textbook pi in the sky nonsense you peddle it totally useless.

14. March 2013 at 18:37

This doesn’t add anything to the conversation, but there’s no option to PM here. I really like Geoff’s contributions to the comments section of this blog.

14. March 2013 at 19:15

Three years after the easy money of 1929-1930 we had a big Roosevelt inflation. Long and variable lags!!!

Three years after the tight money of 1987-1988 we had a huge banking crisis. Once again, long and variable lags!!!

Being sacarastic, if it’s not obvious.

14. March 2013 at 19:16

Being dyslexic, too!

14. March 2013 at 23:39

“A thought; I read somewhere that movements in the fed funds rate often comes from open “mouth”, rather than open market operations. That makes changes in the fed funds rates seem more like managing expectations, rather than actual currency injections.”

Not really, it just means that the operational target is an interest rate and not money quantity. And since the 1990s, the Fed has been explicit about what the Fed Funds target is, so nobody has to guess.

14. March 2013 at 23:51

Scott, I have a quibble with this presentation. Even the most naive non-economist knows that inflation matters when considering the meaning of interest rates. To play fair you should graph the “real” interest rate as well.

15. March 2013 at 03:07

OhMy,

Yes, you get much the same result as if you asked a second-hand car dealer whether his sales are determined by factory output. It’s a fallacy of division to assume that restrictions that apply to a system as a whole apply to every part of the system.

“the CB has no choice but to supply it at the rate it sets.”

– should read-

“the CB supplies it to set the rate it wants.”

A monopolist has no more and no less control over the price of what she sells than the quantity of what she sells. Saying that a monopolist who targets a price rather than a quantity has “no control” over the quantity is utterly misleading, which is why it’s said.

15. March 2013 at 04:10

[…] See full story on themoneyillusion.com […]

15. March 2013 at 05:29

TravisV, they only have the May 2012 issue on their website. You’ll need a subscription to access the rest.

15. March 2013 at 06:23

Silentkz, Debt growth may or may not be sustainable. (Obviously no trend that exceeds NGDP growth is sustainable forever.) But any downward adjustments in debt are easier to accomplish in an environment with stable NGDP growth.

Nick, Yes, I recall that day as well. I was too young to worry very much.

Doug, As I said, the base is a lousy indicator. But using a log scale wouldn’t change much, both M growth and inflation accelerated sharply during the 1960s.

Michael, Here’s my answer. Bernanke thinks the economy needs dramatic ACTION by the Fed. And he also knows that theory suggests that changing the policy goal is the most effect way to ge tmore action. In a perfect world you’d never change the policy goal. But if there is a crisis it may be the lesser of evils.

I’m trying to move us to a policy regime (NGDPLT) where the Fed doesn’t have to change the policy goal in a crisis.

Geoff, I’d say that an indicator is not bad just because it gives a different reading from another indicator that is bad.

Grim23, It’s very hard to visualize because these things are playing out in a complex way. NGDP has a powerful effect on rates, even short term rates. NGDP depends partly on future expected NGDP, which depends partly on future expected changes in money supply and money demand. A given change in the base can directly impact the fed funds rate via the liquidity effect, but the indirect effect through NGDP growth depends on many factors, including whether the monetary shock is likely to persist in the future, which is a forecast of future monetary policy. And shifts in expectations of future monetary policy tend to be “invisible” to the average person reading the paper, and hence interest rate changes caused by that factor are attributed to something else.

OhMy, You should read Nick Rowe on this. The base is endogenous while the interest rate peg holds, but the Fed occasionally adjusts the interest rate peg in such a way as to move the base where they’d like it to be. So over longer periods of time it makes more sense to view the base as exogenous and interest rates as endogenous.

Tyler, What is PM?

Max, We don’t know the real interest rate in the 1930s, indeed we don’t even have good estimates. I would also note that real interest rates soared in late 2008 and 99.9% of economists didn’t notice. That tells me that most economists use the nominal rate.

But let’s say you are right. That means ultra-tight money between June and early December 2008 caused real rates to soar from 0.57% to 4.2%, one of the most dramtic increases in history. That’s my theory of what caused the deep recession—tight money! But almost no one agrees with me. So even if you are right, it’s a huge win for me.

15. March 2013 at 07:00

I will start assembling graphs that illustrate market monetarist arguments

This is very good, these kinds of resources are very helpful in promulgating new ideas to new audiences.

15. March 2013 at 07:10

Re 1987 — I was very young, but I distinctly remember the Fed promising they would print as much money as it took to keep liquidity in the system and prevent a depression. As a preteen I had no idea how this worked, but everyone was pretty relieved when things recovered the next week. Expectations uber alles.

15. March 2013 at 07:54

How about this mission:

Which recession was worse? The recession that occurred after the recovery after the Great Depression, or the recession that occurred after the recovery after the 1987 stock market crash?

15. March 2013 at 08:10

As David Hume noted, knowing what CAN happen, is not the same thing as knowing what OUGHT to happen.

Even if one were correct to argue that a recession will be less worse (meaning lower “unemployment” and lower “output” decline) after a crash with government inflation and spending than without, it is still not an argument to infer from this that government inflation and spending ought to take place during or after a crash.

Economists should not be in the business of imposing value judgments on other people, holding “employment” and “output” over their heads like the sword of Democles.

If “employment” and “output” were really the true goals, then we should be honest, stop deceiving ourselves and others, and advocate right now for the government to print enough money and hire every unemployed person to “work” and produce “something” at the behest of the government. That will make “unemployment” fall to zero, and it will make “output” would expand.

If we want a governmental institution to “save us”, then we ought to stop half assing it and stop whining for directionless inflation where the new money will be spent who knows how or where.

Seems there is this half in, half out, on again off again, maybe maybe not, humming and hawing over whether or not “employment” and “output” are the true goals, in MM theory. Whenever pressed on this, it’s “Oh no, that’s too extreme.” Then employment and output are NOT the goals. But when not pressed on this, it’s “Look at all this unemployment and sluggish real growth! We need the government to inflate and spend more.”

15. March 2013 at 11:36

PM means “private message”; normally I wouldn’t take up comment space just to compliment another commenter.

I realize you’re not running a forum here, but a lot of times these comment threads spin off into multiple conversations. Maybe a MM forum would be a good idea, especially if you could get buy-in from Bill, Lars, Marcus, etc.

15. March 2013 at 11:41

Tall Dave:

“Expectations uber alles.”

Suppose I expect price inflation to double over the course of next year. Suppose my expectation will turn out correct.

Suppose I am living paycheck to paycheck.

How can I fully absorb the consequences of what I expect in the future, right now in the present, such that my plan will prevent me from incurring any losses?

15. March 2013 at 12:06

Geoff,

Are you asking for yourself, or a friend? 🙂 My remark was for the markets as a whole, but okay.

First, it depends what price inflation doubles from. If it’s from .5% to 1% you probably don’t care. 5% to 10%, you probably want to think about it.

What can the low income do to take advantage of expected inflation increases? Well, let’s see: 1) borrow money 2) buy durable goods sooner 3) ask for a raise or look for a higher-paying job.

But those are all obvious, so I guess I’m not sure what your point is.

15. March 2013 at 12:08

The 2 are uncomparable.

15. March 2013 at 12:09

for the government to print enough money and hire every unemployed person to “work” and produce “something” at the behest of the government.

That’s like arguing the best solution to a paper cut on your thumb is to cut off your hand. Sure, it solves the problem, but it doesn’t exactly improve the situation…

15. March 2013 at 12:28

and it will make “output” would expand.

I think this is where you’re confused. Output is measured by prices x quantities. Let’s say you have them produce toilet handles, which currently go for, say, $10 each. Now, say your army of unemployed produces a billion of them, say 10x the current production. Did they produce $10B? No, because the price is now essentially zero.

The question of how to maximize output is one that cannot be answered by any single person or institution. The answer is only divined (and badly, at that) by the trillions of daily decisions made by the world’s 7 billion consumers.

15. March 2013 at 13:31

Suppose I expect price inflation to double over the course of next year. Suppose my expectation will turn out correct. Suppose I am living paycheck to paycheck. How can I fully absorb the consequences of what I expect in the future, right now in the present, such that my plan will prevent me from incurring any losses?

Why would you incur any losses?

Inflation is a general increase in all prices — including wages, which most definitely are prices.

Look at the record at FRED or wherever you want, nominal wages track inflation with a 99% correlation — in fact, with a 99.56% correlation in this data…

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=gBB

… if we want to be precise — because rising nominal wages *are* inflation.

Significant price rises without wage rises are not inflation, they are a price shock, with the impact on the real economy of a price shock.

You can’t have inflation — a general rise in *all* prices — without rises in as *huge* a portion of prices as wages represent.

So as you expect wages to go up with inflation, why would you expect a loss on wages from inflation?

15. March 2013 at 14:17

“PS. I’ve started work on two projects. One is an online money class, and the other is a book based on my blog.”

+1 — I want to sign up for the class and buy the book.

15. March 2013 at 14:49

I’ll be guest starring in the chapter called “monetary ignorance”.

15. March 2013 at 20:35

@ OhMy…

the monetary base is endogenous. The private sector lends, borrows and demands cash and the CB has no choice but to supply it at the rate it sets. So yes, the base is a good indicator of what the economy is doing, but it is not something the CB can control.

Yes, yes, and once I set the rate that my car will move I have *no choice* but to supply the amount of gasoline to the engine that is required for it to move at that rate, uphill, downhill or whatever. Thus I have *no control* over what my foot does on the gas pedal.

I ran around this mulberry bush with Warren Mosler himself on sci.econ 15 years ago or so, back in the glory days of usenet.

He and his acolytes were calling themselves Chartalists and/or New Chartalists back then. Not very catchy. Since then they’ve done a great job of re-branding their church as “MMT”, but its doctrine is none the better for it. (And as DeLong points out, “MMT” itself is a serious misnomer, as there is nothing either M or M about it.)

15. March 2013 at 22:12

Good to hear you’re writing a book. As a second-year econ student, I can’t wait to understand what I’m reading.

16. March 2013 at 06:19

Geoff, You said;

“Even if one were correct to argue that a recession will be less worse (meaning lower “unemployment” and lower “output” decline) after a crash with government inflation and spending than without, it is still not an argument to infer from this that government inflation and spending ought to take place during or after a crash.”

I completely agree.

Tyler, Thanks for the tip.

Thanks Michael and Omar.

23. March 2013 at 09:23

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, I’d say that an indicator is not bad just because it gives a different reading from another indicator that is bad.”

How about comparing them to a standard other than mere difference?

TallDave:

“First, it depends what price inflation doubles from. If it’s from .5% to 1% you probably don’t care. 5% to 10%, you probably want to think about it.”

Suppose for argument’s sake I do care.

“What can the low income do to take advantage of expected inflation increases? Well, let’s see: 1) borrow money 2) buy durable goods sooner 3) ask for a raise or look for a higher-paying job.”

Wouldn’t borrowing rates reflect inflation? I’d pay a higher interest rate. Buy durable goods? Wouldn’t their prices rise on me? Ask for a raise? What if my employer’s revenues rise after other’s revenues rise when there is inflation?

“But those are all obvious, so I guess I’m not sure what your point is.”

Keep going…

Jim Glass:

“Why would you incur any losses?”

I could be paying higher prices without having an increased income.

“Inflation is a general increase in all prices “” including wages, which most definitely are prices.”

Increasing the supply of money doesn’t affect all goods and prices at the same time. I am talking about the money injected by the Fed into the banks first, who then spend it, and then that money is respent. At some point, yes, the average person’s income will rise above where it otherwise would be, but not all individual incomes rise at the same rate.

“Look at the record at FRED or wherever you want, nominal wages track inflation with a 99% correlation “” in fact, with a 99.56% correlation in this data…”

Aggregate nominal wages do not distinguish among individual wage rates. If one person’s wages rise, but another’s does not, because inflation hasn’t extended long enough, then aggregate wages will still register a rise, despite there being no rise for other wage earner.

” if we want to be precise “” because rising nominal wages *are* inflation.”

That’s just a definition, not precision.

“You can’t have inflation “” a general rise in *all* prices “” without rises in as *huge* a portion of prices as wages represent.”

You can’t have a general rise in prices without some prices rising more than others because of inflation entering the economy at points, not everyone’s accounts.

“So as you expect wages to go up with inflation, why would you expect a loss on wages from inflation?”

I am not talking about “wages”, I am talking about “Bill’s wages”, “Steve’s wages”, “Mary’s wages”, etc.