Why does demand affect prices?

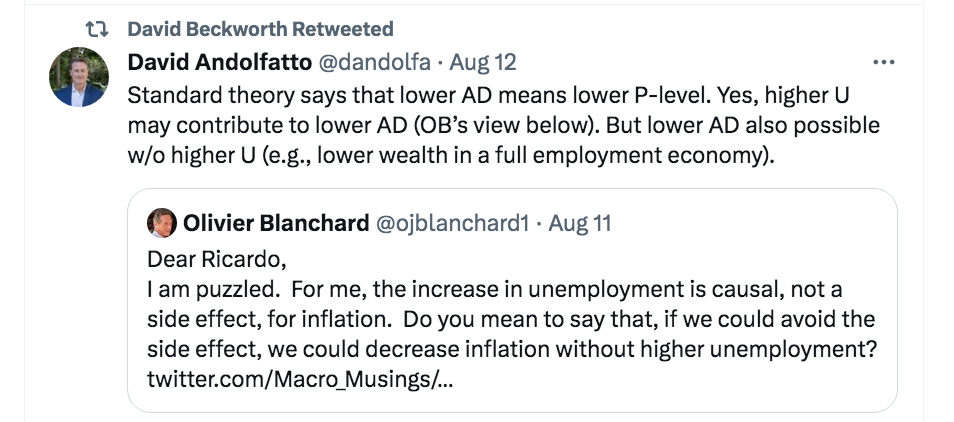

Unfortunately, macroeconomists lack a common framework for thinking about how the macroeconomy works. David Beckworth directed me to a tweet that nicely illustrates this problem:

First, let me agree with Blanchard on one point. I would certainly expect a decline in inflation to be associated with a rise in unemployment. But his claim about the causal mechanism seems so strange to me that I even have trouble thinking of a way to explain why we disagree. If a student asked me “why does Blanchard think higher unemployment would reduce inflation?” I’d have trouble answering the question. That doesn’t mean he’s wrong, (he’s a far more distinguished economist than I am), it’s just that our approaches are so different.

Instead of starting with a sort of extreme Chicago/monetarist argument, let me start with an idea that once had strong support among Keynesian economists—incomes policies. Back in the 1970s, left-of-center economists in places like the US and Europe favored “incomes policies” (basically wage/price controls, with an emphasis on wages) as a way of reducing inflation. They didn’t believe this policy would do the job all by itself, rather they argued that it would allow other policies that slowed the growth in aggregate demand to reduce inflation with less of a side effect of high unemployment. So why did they believe this?

At the time, I assumed that incomes policy proponents bought into the “sticky wage/price” theory of macroeconomics. This is the idea that demand shocks have real effects because wages and prices are sticky in the short run. (Some argue that in the long run money is neutral and output returns to a natural rate. But that claim has no bearing on this post.)

So Keynesians seemed to believe that demand-side policies that reduced the growth rate of nominal spending would involve more output and less inflation if wages and prices could somehow be made more downward flexible. Incomes policies (if effective) were supposed to do this:

Lower NGDP —> Lower inflation & stable output

Here I have no interest in the question of whether incomes policies were effective; rather I’m focused on the mechanism by which they were supposed to work. It seems to me that that mechanism is completely at odds with Blanchard’s view of the problem.

I agree with Ricardo Reis, we should think of unemployment as an unfortunate side effect of policies that restrain demand to control inflation:

1. Contractionary demand side policies –> falling nominal spending

2. Sticky wages and prices

3. Reduced inflation as well as lower employment/output

Aggregate nominal spending is P*Y. If nominal spending falls by 10% and prices only fall by 4% (due to sticky wages and prices), then output and employment will necessarily decline. But that employment decline doesn’t seem causal.

When people talk of a causal role for unemployment I see:

1. Lower employment

2. ???

3. Lower inflation

To some people, that causal relationship might seem obvious. But to me it seems much more natural to see unemployment as a side effect. If wages and prices were completely flexible, it’s hard to see how changes in nominal spending would have any real effect on employment or output. In that case, what would be the causal mechanism between nominal spending and inflation?

You might argue, “But wages and prices are not completely flexible in the real world.” Yes, but that’s not the point when trying to understand the causal mechanism. If it were really true that unemployment is the causal mechanism, then in a world where wages and prices were 100% flexible and the economy always stayed at the natural rate there’d be no way to slow inflation with contractionary monetary policies. Does anyone believe that?

Recall that a lower price level is equivalent to a higher value (purchasing power) of money, the unit of account. Blanchard is basically saying that the only (demand-side) mechanism by which we can give money more value is by creating unemployment. Now consider a microeconomic analogy to his claim:

Assume a shock to the apple market that raises the equilibrium price of apples, such as a change in consumer preferences or a crop failure. That rise in apple prices might be associated with a situation where grocery stores were temporarily out of apples. Maybe they didn’t immediately raise the posted price, and consumers exhausted the existing stock.

Even if there were a temporary apple shortage, I think it would be weird to view the shortage as causing the higher apple prices—it was the reduction in supply an/or the increase in demand that caused the higher apple prices. There might be a temporary shortage if apple prices were sticky. But I can also imagine a scenario where apple prices were flexible, and there were no shortages during the transition to higher prices. In that case, in what sense would shortages be the causal factor for higher prices? You can reverse this example for surpluses of apples when the price declines.

When overall inflation declines, it’s the reduction in AD and/or the rise in AS that causes the decline. Unemployment might rise as a side effect, but it’s hard to see how it’s the causal factor. It’s an unfortunate side effect of sticky wages and prices leading to disequilibrium. But disequilibrium doesn’t cause the lower inflation; indeed inflation would actually fall faster if the real economy stayed at equilibrium when nominal spending slowed. In that case, a sudden 10% fall in NGDP would immediately reduce prices by the full 10%.

Here’s another example. Apartment rents often decline when there are a lot of vacancies. But building a lot of new apartment buildings should reduce rents even if the vacancy level never rises. Vacancies aren’t a causal factor; they are evidence of a market out of equilibrium. It’s the supply and demand for housing that drive the process.

Even if the correlation between lower inflation and higher unemployment were 100%, if wages and prices were always sticky, it still doesn’t make unemployment causal. If you told me that 100% of people with Covid had a fever, I still wouldn’t believe that fevers cause Covid.

Update: Ricardo Reis has an excellent thread on this issue.

PS. I have a related post at Econlog.

PPS. As an aside, the 1971-74 incomes policy failed in the US because policymakers failed to enact contractionary fiscal and monetary policies during the control period. So the proposed policy was never actually tried. NGDP growth remained very high and (not surprisingly) inflation rose after the controls were lifted. I’m not a fan of incomes policies, just pointing out that this outcome has no bearing on the issues in this post. I mentioned incomes policies only to better understand the thought process of its Keynesian proponents.

Tags:

13. August 2023 at 16:23

“The increase in unemployment shifts the consumption function down (red line), since the agent cuts consumption to accumulate more precautionary savings. The impulse response function on the right side shows indeed that the saving rate increases in response to higher unemployment.” —IMF – Precautionary Savings in the Great Recession

Unemployment > less consumption > less AD

That’s causal, right?

13. August 2023 at 18:30

Ahmed, That reverses cause and effect. It’s lower AD that causes lower employment. The question is why does lower AD cause lower inflation? Is it only by reducing employment, or might it directly reduce inflation.

13. August 2023 at 20:17

‘If you told me that 100% of people with Covid had a fever, I still wouldn’t believe that fevers cause Covid’

But would you believe that covid might cause fever?

13. August 2023 at 20:31

Off-topic, but related to the concept of equilibrium, I just put up a blog post that features some charts with imputed GDP output gap data, based on divergences between NGDP growth and the S%P 500 earnings yield.

For reasons I address in the post, this approach is really not useful for data prior to about 1996 or so. However, since then, the imputed output gaps look pretty plausible.

https://exactmacro.substack.com/p/stock-and-gdp-outlook-for-week-ending-f53

13. August 2023 at 21:07

Rob, Yes, I already believe that.

Michael, Is that gated?

13. August 2023 at 21:14

I’m rambling here, but let me do a Thanos snap type of experiment:

-Half the population disappears instantly, therefore:

-Aggregate Demand drops by half instantly, therefore:

-A probable rise in the unemployment rate regardless of any interest rate policy or prior inflation rate.

-All real estate and every other tangible asset loses half its value, and there’s cash just lying around everywhere, therefore:

-Inflation soars, right?

Extreme example I know, but maybe a way of demonstrating how a systemic shock to AD can overwhelm any clear relationship between interest rates, unemployment, inflation, etc…

13. August 2023 at 23:00

Interesting, not having ever studied formal macro, I assumed something like this:

1- Unemployment is very low, so demand of labor is higher than supply, and wages go up

2- This raises AD, whereas AS has a large lag, so inflation

3- Inflation causes worker to demand higher wages, and due to low U, they have leverage and succeed

– So the cycle repeats

Increasing unemployment changes the labor demand/supply balance, so employers no longer have to keep increasing wages, and the cycle can stop

I guess my question is why that’s wrong?

14. August 2023 at 06:16

There’s no such equilibrium phenomenon between AD and employment. There are leakages. Money is not neutral. Savings is not synonymous with the money supply.

Link: “Changes in Wealth and the Velocity of Money”

https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/87/03/Changes_Mar1987.pdf

14. August 2023 at 06:36

@David that sounds to me like its

1)MASSIVELY increasing in RGDP per capita in the short run and

2) Leads to a GIGANTIC increase in demand for labor (i.e. near 0 unemployment).

Suddenly we have twice the amount of fixed assets for productive capacity per capita. Sure they wont be run optimally, but I think it is more than reasonable to expect production to drop by meaningfully less than half.

So we have greater output and greater assets per person, so Real GDP per capita should have a big bump higher.

In terms of the money out there, I will presume to answer for Prof. Sumner, what’s left of the Federal Reserve Board should reduce the monetary base by roughly half so there’s no inflation.

If you’re targeting NGDP per capita levels it would even be massively deflationary as the price level would have to keep NGDPpp at target if RGDPpp increases.

Combine this example with Prof. Sumners barter economy thought experiment and its obvious there’s no reason for inflation.

https://www.econlib.org/how-do-barter-economies-avoid-inflation/

14. August 2023 at 06:51

Scott,

No, it’s not gated. I don’t charge to read the blog. I may charge for access to some related data I provide on it website I’m building, in addition to the stock portfolio stress-tester.

14. August 2023 at 06:56

Just speculating here … what about a (mistaken) theory like this: Wages are fixed (at least in the short term). Therefore, with unchanged employment, national income is fixed. Aggregate demand equals total national income. Therefore, reducing aggregate demand is only possible by increasing unemployment, which will thereby reduce total national income and therefore aggregate demand.

Is that not a “plausible” “Phillips curve” macro story?

Just look at @David S’s question above. “Half the population disappears … therefore AD drops by half”. Surely he has in mind a model something like I’ve just described. That AD = total income.

(By the way, David S: if half the population disappeared … why would unemployment rise? Surely instead you would immediately find there are two jobs available for every worker, which instead suggests that unemployment should immediately plummet to zero.)

14. August 2023 at 06:56

Ah, it was gated, but by accident. I misclicked last night when I posted it.

14. August 2023 at 08:21

As I understand how AD affects prices, given changes in AD, sticky wages, in the short-run, make for sticky short-run inflation, and hence changes in real GDP, also in the short-run. Sans sticky wages, inflation would have no real effects, as all prices would fully adjust in unison.

If AD increases due to expansionary monetary policy, for example, ceteris paribus, most of the change in NGDP will be in real GDP, in the short-run. Inflation will rise some, but it is limited by sticky wages, which limit consumption increases, for example. Such increses in AD lower real wages, in the short-run. Consumption increases in proportion to the rate at which inflation is expected to rise, subject to short-run budget constraints.

In the long run, wages do fully adjust, and above capacity real GDP growth reverses as inflation increases. This can mean that an unsustainable boom leads to a more or less mirror image recession, ceteris paribus.

14. August 2023 at 09:58

Michael, There are some weird output gaps on the graph. Output further below normal in 1989 than during the Great Recession? Overheating in 2003? Hmmm . . .

David, Why would half the population leaving reduce AD? As you suggest, might not it simply double the price level—at least if the money supply were unchanged?

Babak, Yes, disequilibrium is clearly possible–no one disputes that. But why is disequilibrium necessary to cause changes in wages and prices? Prices can also change in equilibrium when S&D shifts.

Don, You said:

“Just speculating here … what about a (mistaken) theory like this: Wages are fixed (at least in the short term). Therefore, with unchanged employment, national income is fixed.”

That doesn’t follow. If wages are fixed than when AD goes up there’s an increase in national income caused by more hours worked and higher profits. If employment is also fixed (why assume that?) then higher profits.

14. August 2023 at 11:13

Scott,

Yes, as I explain in the blog post, the numbers look silly before roughly 1996. I provide the expanded graph first to make sure it’s understood that the model, to the degree it works, only works in the post-gold standard, Great Inflation era in which earnings yields weren’t elevated due to things like both high current and expected inflation, tax bracket creep, etc. I then provide the zoomed in model that focuses more on the time frame over which the model is relevant, if it is at all.

And while I understand that you don’t think the economy was running hot in 2003, given the prior NGDP growth path, it’s not as if it’s an uncommon opinion, and as you well know, even David Beckworth and George Selgin wrote a paper in which they argued that money became loose during that period.

However, at a glance at least, much of this looks very plausible after 1996. Notice that this chart shows the economy approaching equilibrium in 2017 and 2018, as you’ve claimed, and then falling further below capacity in 2019 after Fed tightening. It certainly shows the overshoot during the pandemic recovery.

This could all be coincidence, of course, but it seems unlikely that this approach has no merit. It’s obviously based on the classical concept that the rate of return on capital should equal the economic growth rate. And obviously current earnings reflect much about current economic growth, while price reflects future expected earnings, so changes regarding these variables would seem to necessarily capture the short-run versus long-run health of the economy.

14. August 2023 at 11:33

Also, I just recalled that the Jobs And Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 was passed in May of that year. Before its passage, the S&P 500 was up a bit over 4% for the year, but finished the year with a greater than 26% gain. That certainly could have distorted the earnings yield, making it appear the economy was overheating, sans a proper adjustment.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/j/jgtrra.asp#:~:text=The%20law%20reduced%20the%20long,as%20long%2Dterm%20capital%20gains.

Such distortions are rather rare, but they do occur.

14. August 2023 at 12:52

Michael, Sorry, but those gaps don’t look right to me. Suggesting other people might have made the same mistake about 2003 (which I doubt) doesn’t help your argument.

The Great Recession looks all wrong. So does the tech boom of 2000. You have the line going downward from 2003 to 2006, which makes no sense to me.

14. August 2023 at 15:04

Scott,

Well I appreciate your opinion, even if I disagree. I think you’re right that policy was probably not too loose in 2003, but I’ve also learned that in the rare cases in which I disagree with Selgin, for example, to feel far less than comfortable. I’ve done the calculation before, and NGDP growth did not rise above the long-run average during this period, but perhaps Selgin and Beckworth would disagree with the baseline I used, or perhaps I made a mistake somewhere. I think it’s much more likely that the tax bill I referred to lowered the earnings yield, distorting the imputed output gap calculation.

Here’s a link to the Selgin/Beckworth paper I refer to, by the way:

https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/alt-money-univ-reading-list/beckworth-productivity.pdf

I don’t know why you think the Great Recession looks “all wrong”. I think the dates listed might be confusing, in that they’re dated 01-01-“year”, for example, which can create the impression that maybe the whole series should be shifted forward one year. 01-01-2009 really refers to 2008, for example.

I’m not sure why you think the tech boom looks wrong.

As for the graph going down from 2003 to 2006, both real and nominal GDP also declined over this period, so I don’t know why that looks wrong either.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=17R7w

14. August 2023 at 16:59

I’m in agreement with you about unemployment being a side-effect, but this got me thinking about the best story one could tell where unemployment is causal in reducing inflation. Here is one possibility: suppose the supply curve of consumer goods is very elastic, so a fall in demand has no significant first-order effect on inflation. But the reduction in labor demand leads to a slowdown in wages. Now let’s say firms are in perfect competition, with pure profits equal to approximately zero, so they slow down their price increases in tandem with their wage increases.

I think that’s a coherent story. But as far as I know it doesn’t fit the basic facts of the 70s, which is that the CPI was much more volatile than wages and that the 1980 disinflation started before the wage disinflation.

14. August 2023 at 19:31

Great post, Scott. Maybe previous commenters have suggested something similar, but the sense I get from people like Blanchard (and also from some central banks like the RBA these days), is that he/they derive their policy views from cost-push theories of inflation, which – contrary to one of Reis’s other points in his podcast discussion with David Beckworth – takes the Phillips Curve as a causal mechanism: Labour market ‘slack’ leads to wage moderation, which in turn leads to price moderation. The same happens for commodities. The inbuilt assumption seems to be that nominal rigidities are the natural state of the world, and wages or prices only adjust in respond with a lag to tangible evidence of either queues or overflowing shelves. As you say, where would this leave monetary explanations for inflation in a flexible price world? I wonder if this view of things has become more common in recent years, as suppliers who raised prices during Covid were condemned for ‘profiteering’.

14. August 2023 at 19:56

Sorry, this is a duplicate comment, as your site moderator doesn’t seem to like me commenting in the same name from a different computer…

Great post, Scott. Maybe previous commenters have suggested something similar, but the sense I get from people like Blanchard (and also from some central banks like the RBA these days), is that he/they derive their policy views from cost-push theories of inflation, which – contrary to one of Reis’s other points in his podcast discussion with David Beckworth – takes the Phillips Curve as a causal mechanism: Labour market ‘slack’ leads to wage moderation, which in turn leads to price moderation. The same happens for commodities. The inbuilt assumption seems to be that nominal rigidities are the natural state of the world, and wages or prices only adjust in response with a lag to tangible evidence of either queues or overflowing shelves. As you say, where would this leave monetary explanations for inflation in a flexible price world? I wonder if this view of things has become more common in recent years, as suppliers who raised prices during Covid were condemned for ‘profiteering’?

14. August 2023 at 22:25

Michael, You said:

“both real and nominal GDP also declined over this period”

No, they didn’t. They rose above trend.

Philippe, My problem is that he implies unemployment MUST be a part of the process.

Rajat, I wonder how Blanchard would explain the high inflation of 1933-34, when unemployment was 25%.

15. August 2023 at 03:11

Scott,

I link to the annual change in GDP growth data above. I see it going down from 2003 straight into the Great recession.

15. August 2023 at 03:15

Ah,I left the word “growth” out of my original statement above. Sorry about that. I meant to say GDP growth fell over the relevant period.

15. August 2023 at 11:13

Michael, You are missing the point. NGDP growth was above trend. Money was easy. A fall from 7% to 6% doesn’t mean money is getting tighter, we are rising further and further above the trend line.

The last 7 quarters are another example (although I expect NGDP growth to speed up in Q3.)

16. August 2023 at 03:53

Scott,

Yes, I just did the math, and NGDP growth was above trend, even excluding the early 2000s recession, and inflation was rising. So, you certainly have a strong case for saying the economy was running hot over that period.

But, that assumes that the previous trend path represented equilibrium. My own proposed metric suggests that equilibrium was roughly reached in the year just prior to the period mentioned, so that doesn’t seem to help my case.

Perhaps its better to interpret the output gap as an expected output gap, if the concept has any validity at all.

17. August 2023 at 08:42

But if we were still below equilibrium during 2003-06, we were getting closer.

17. August 2023 at 10:34

Well, the chart I produced would indicate a prediction of being above equilibrium as of 2003, though that data might be distorted by the dividend and capital gains tax cuts that year. Then, it predicts a growing negative output gap after that going right in the the Great Recession. And the point when this changed is when the Fed starting raising interest rates, and NGDP growth began to fall.

There was obviously a growing differential between current and expected NGDP growth, if you buy that interpretation of the S&P 500 earnings yield.

18. August 2023 at 13:25

Thank you for taking the time to respond! Thinking about this, I guess it makes sense that employment disequilibrium is not necessary to have (non-transitory) inflation, but it still is sufficient, right? Couple that with historically low unemployment (depending on your favorite measure), and I could see how many of us would assume that’s the culprit, or at least should be the focus.

On the other hand, you seem to go beyond just saying that higher unemployment is not the intended cause of disinflation, to saying it cannot be the cause? If that was the easiest lever to me and I could pull it, wouldn’t higher unemployment lead to lower AD in the short term, and slow inflation?

Reading Ricardo’s thread, as well as that of Blanchard and Krugman’s column today, I (think I) understand the monetarist model and argument, but it leaves me not knowing what I don’t know and how it ties back to sending behavior / etc. On the other hand, the “demand side” arguments if you can call them that, are intuitive to understand, even if they leave me wondering what’s unsaid. So whether we raise rates to slow inflation through unemployment or not (on a human level, I’d say those making the decision should tell us which!), do you agree that higher unemployment can cause lower AD < lower inflation, whether at a labor disequilibrium or not? I think a counter-argument would say that it would also reduce supply/production, but the key there is the lag associated with the latter (and not so much the former).

More importantly, if through another causal mechanism, what is it in terms of behavior / AD-AS? If more savings and less investment, does that act fast enough and should we see it in data (that Krugman says we don't, today)?

18. August 2023 at 16:03

Babak , You said:

“wouldn’t higher unemployment lead to lower AD in the short term, and slow inflation?”

I could quickly create lots of unemployment by raising the minimum wage to $40/hour. But that would not reduce inflation. Yes, if you raise unemployment with a tight money policy then inflation will fall. But it’s the tight money doing the job, not the unemployment. If there was no unemployment during the tight money period, then inflation would fall even faster.