Why do the best arguments against the RBC model involve exchange rates?

The “real business cycle” model has led some conservatives to claim that monetary stimulus will merely lead to more inflation, not more real economic growth. They don’t believe that nominal shocks have real effects.

The two most famous arguments against the RBC model both involve exchange rates. One argument was discussed in a recent post by Paul Krugman. He presented a graph showing that real exchange rates became vastly more volatile after the Bretton Woods exchange rate regime was abandoned around 1971. You might ask: So what? Is it any surprise that exchange rates became more volatile after the world abandoned fixed exchange rates? It’s not surprising that nominal rates got more volatile, but real rate volatility is a bit more of a surprise. Recall that the RBC model predicts that nominal shocks won’t have real effects. (Indeed even some non-RBC types like Milton Friedman didn’t expect such dramatic volatility.)

A second example was recently discussed by Ryan Avent; the famous study (by Barry Eichengreen) that showed countries tended to begin recovering from the Great Depression precisely when they left the gold standard. Again, if nominal shocks don’t have real effects (as some RBC proponents claim), then this pattern is hard to explain.

I don’t recall anyone explaining why economists use foreign exchange data to refute the extreme RBC view that nominal shocks don’t matter. After all, nominal shocks are also supposed to have real effects in closed economies. Why not use a more conventional indicator of monetary stimulus, such as the money supply, or interest rates, or the inflation rate? One answer is that it’s very hard to identify monetary shocks using those indicators. Low rates may reflect easy money, or they may reflect a weak economy expected as a result of tight money. A big increase in the money supply might reflect easy money, or might be the Fed accommodating more demand for base money in response to past deflationary policies. The rate of inflation might rise due to supply shocks, or due to demand shocks.

In the interwar period there was a pretty good correlation between money, prices, and output, as there were big monetary shocks that led to procyclical movements in the price level. That looks good for conventional demand-side models. But postwar data is less clear. Now the monetary authority tries to offset changes in velocity, so money and prices are much less clearly correlated with output.

Exchange rates are almost ideal in two respects. Unlike interest rates and the money supply, a rising value of the dollar is a relatively unambiguous indicator of tighter money, and vice versa. And unlike changes in inflation, it’s pretty easy to separate out changes in exchange rates that reflect exogenous policy decisions, and those that reflect other factors. For instance, both the abandonment of the gold standard, and the abandonment of Bretton Woods were pretty clearly exogenous policy decisions. Indeed they were “monetary policy” broadly defined to include “changes in the international value of one’s money.”

I prefer NGDP, but many of my critics say that indicator assumes away the question. How do we know central banks can influence NGDP? I think that’s wrong, especially if you use expectations, but nevertheless exchange rates are clearly something that governments can control.

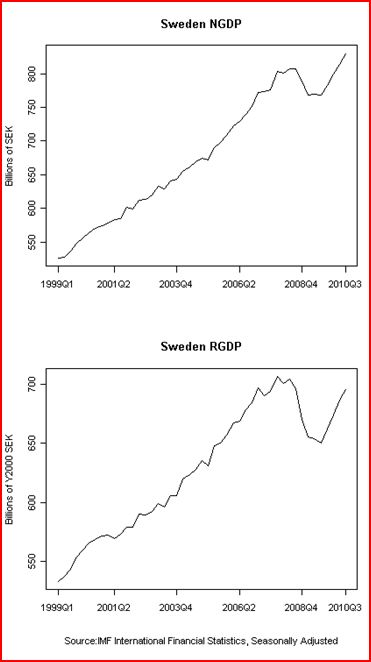

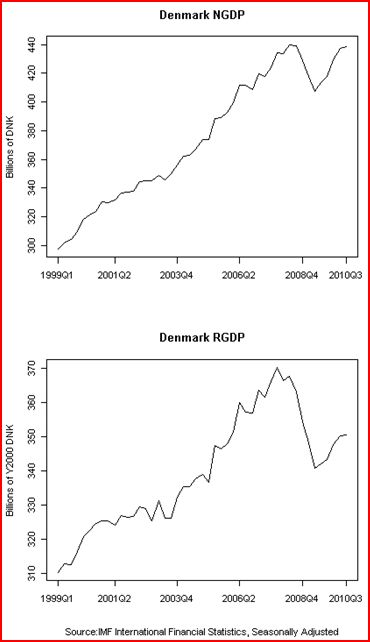

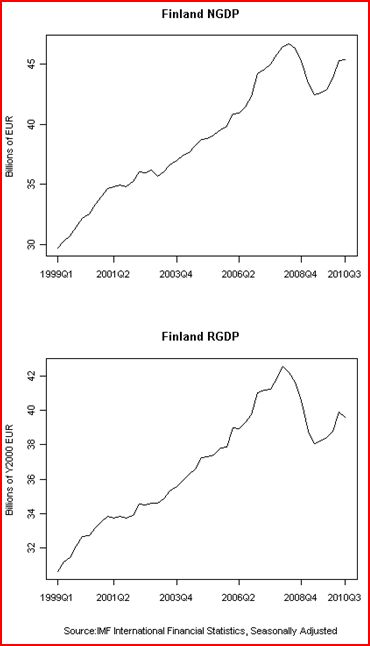

I recently mentioned some very suggestive data for Sweden and Denmark, and a commenter named Justin Irving (a student at Uppsala University) sent me data which repeats the two famous experiments that I cited above, albeit in a slightly less impressive way (only three observations.) He sent me graphs showing NGDP and RGDP for three major Nordic countries. (Norway was not included, presumably because its vast oil wealth would make it an unrepresentative country.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

In 2008 both Denmark and Finland were either in the euro, or fixed to the euro. Sweden was floating, and as soon as the recession hit it allowed the krona to depreciate sharply. As you can see from the graphs above, Sweden’s NGDP grew significantly faster than the other two. This is no surprise; both RBC and conventional macro models would predict this result. But now look at RGDP growth. The RBC model suggests that devaluing a currency will simply result in higher inflation, not faster RGDP growth. Yet it’s clear that Sweden did much better than Denmark and Finland in terms of RGDP. Why is that? I believe the faster NGDP growth caused the faster RGDP growth. A real business cycle proponent would presumably say it was just coincidence, just as it was coincidence that America started recovering in 1933 and France began recovering in 1936, etc. Lots of interesting coincidences.

All these natural tests of the RBC model lead me to wonder what we can infer from the fact that economists use exchange rates, not conventional monetary indicators, when attempting to refute the RBC. What does that tell us about contemporary monetary economics? Here are some answers:

1. Postwar conventional macro models that identify monetary shocks on the basis of interest rates or money supply changes are not reliable. Instead when researchers want convincing evidence they reach back to the definition of monetary policy provided by that “monetary crank” of the 1930s, George Warren. Warren proposed that monetary shocks were changes in the price of gold.

2. We need a variable that gives a clear and unambiguous indication of changes in the stance of monetary policy (like exchange rates), and which also can be measured in real time, (like exchange rates.)

3. The best way to get that variable would be for the Fed to create and subsidize a NGDP (and RGDP) futures market.

No longer would we have to wait for serendipitous experiments like the staggered ending of the gold standard, or the end of Bretton Woods. We’d have a perfect real time indicator of monetary shocks. We could observe how Fed actions (and policy speeches) impacted NGDP futures prices. We could observe how changes in NGDP futures impacted various real variables. The actual parameters of all sorts of macro models would lay naked and exposed, like the skeleton of a dead animal lying in the midday Libyan sun. Want to know the slope of the SRAS? Is Plosser right or is Krugman right? Just compare the reaction of RGDP and NGDP futures to a sudden Fed announcement that under the pressure of regional Fed presidents, QE2 was being ended prematurely. Something tells me that Plosser would not be happy with the answer that the markets would give him.

The experiments discussed by Krugman and Avent tell us something important (and unpleasant) about modern RBC models.

The fact that those experiments had to rely on exchange rate shocks tells us something important (and unpleasant) about modern conventional macro.

Tags: Bretton Woods, Real Business Cycle Theory

25. February 2011 at 11:23

The other option is that price level measurements are complete and utter crap.

25. February 2011 at 11:35

You’re good! 🙂

25. February 2011 at 12:06

What is the “real business cycle”? What is a nominal shock with real effects? I don’t speak your language and am not an economist.

But I know this, economic prognostications (nominal & real gDp), are infallible (and always have been).

Just like Lacker says “My sense core inflation has bottomed out – FEB 8 comment. Money flows bottomed in JAN as you could see far back as JULY 2010.

25. February 2011 at 14:51

“The RBC model suggests that devaluing a currency will simply result in higher inflation, not faster RGDP growth. Yet it’s clear that Sweden did much better than Denmark and Finland in terms of RGDP. Why is that?”

The Swedes also cut marginal tax rates and payroll taxes, announced in Sept 2008. How much does this account for in Sweden’s relative outperformance, given that Sweden has maintained relatively high marginal tax rates on labor (much less so on capital and corporate income)?

25. February 2011 at 15:13

Doc Merlin, But crap in precisely the way that would produce this cross country comparison? Possible, but I doubt it. My hunch is that Sweden and Denmark use similar techniques.

Thanks Bogdan.

flow5, RBCs are not caused by factors like monetary policy.

Numeraire, I didn’t know that, it could certainly have been a factor. Did Denmark also cut MTRs? I know they cut UI from 4 years to 2, which is an important supply-side reform.

26. February 2011 at 01:53

Scott,

As a relative newcomer to this blog, (1) where would NDGP futures sit within the universe of arbitrage opportunities (2) how big ( notional amounts, # of say USD 1.000.000 contracts). What sort of interest rates would you expect in your world, etc.

Re Sweden, I do not think that the differences between Finland, Denmark and Sweden’s crisis experience are much better explained by what you suggest here than by simple trade political effects following a devaluation by a country whose producers tend to have short term pricing power in USD (monopolistic competitors in a world market), with Greater German and Japanese firms as their main competitors. It would be interesting to know if the Swedish suppliers of heavy duty transport equipment, for instance, have gained world market share during that period (given that a lot of that is actually produced in the firm’s headquarters country (contrary to many branded consumer products).

Actually, I wish you were right, because that would mean that there is a socially useful way to do macroeconomic policy that would work in small open countries (that try to get rich by stealing from their neighbours) and big, closed countries. I spent most of my life in the firm belief that macroeconomics was interesting, divided, inconclusive, and mainly useful to politicians..(and of course, professional economists)

26. February 2011 at 01:55

Terribly sorry, I should have finished one of the first sentences about the NDGP furures. How big would that market be, how would the clearing house be made default-resistant, etc.

26. February 2011 at 02:39

There is something in modern economics that seems to make people not want to see monetary effects. A case from economic history: it is fairly obvious that the flood of silver from the Americas from 1550, building on the fivefold increase in production from central European silver minds from c.1460, was a central feature driving global trade patterns until about 1830. It priced European goods out of Asian markets (except where there were no competitors) and Asian goods into European markets, as about a third of the total silver mined went into buying Asian goods. (Given silver was the dominant medium of exchange and the Asian economy was much larger than the European one, the price implications are surely obvious: Smith discusses it in The Wealth of Nations [Vol. I, Bk. I, Ch. XI, Pt. III].) Yet one gets perfectly serious economic historians talking about the “strange reluctance” of Asians to buy European goods, or even the “inferiority” of European goods. Or studies of global trade which do not even consider this factor.

Money is how one makes and accepts offers, the basic signaling device of commerce, the markers for transactions. It is not some mere impotent ‘ether’ between goods and services, for it connects all monetised goods and services with each other. It is what you use to stay in the game, to go up and down in the game, how you keep score. What happens to and with your markers therefore matters.

I wonder if (since the language you use affects how you think) whether the language of ‘nominal’ and ‘real’ does some damage here, as if goods and services are all there is to the “real” economy so what happens to mere markers, the “merely nominal”, does not matter.

Or, to put it another way: imagine an economy without money. (I don’t mean without notes and coins, I mean without money at all, just goods and services.) Then try and claim that money does not matter for the “real” economy.

(I have also posted this to the wrong post of yours Scott: sorry, just had a really good dinner. This is where I meant to put it.)

26. February 2011 at 18:46

Rien, I’d anticipate nominal interests being close to the NGDP target, or perhaps slightly below.

I don’t know exactly how big the market should be, I’ve suggested that the Fed subsidize trading so that the market is fairly big and liquid.

I think you misunderstood my exchange rate argument. The point was that the differences in exchange rates clearly reflected different monetary policies in the case (2 countries were fixed). But the RBC theory would not predict any real effects (even in trade) from a purely monetary devaluation.

Thanks Lorenzo, I did see it over there.

26. February 2011 at 19:13

Scott,

But why this focus on Sweden, Denmark and Finland? Finland is not even an Indo-European language speaking country. Would it kill you to insert a graph of NGDP for Poland? A country who’s language actually resembles Swedish or Danish?

Or is the graph to disturbing for you to produce?

26. February 2011 at 21:27

Scott,

As to the RBC theory in general, of course. I am only not so sure that you have observed something significant (policywise) beyond the rather primitive mechanism in my next paragraph).

But I would like to see where those more benevolent GDP changes are located, especially when converted into EUR (keep in mind that we are basically back at pre-crisis levels). What we are likely to see is that the Riksbank gave Swedish workers a temporary pay cut (in EUR terms) that allowed the large exporters to stay competitive and keep those people employed. That in turn, may have prevented a shock to Sweden’s long term potential output in sectors where it is very hard to reproduce.

27. February 2011 at 11:54

[…] take up Sumner´s post and include Polish data. To focus on the more recent period that includes the “crisis”, all the […]

28. February 2011 at 06:15

Mark, Finland is much more similar to Sweden that Poland.

Rien, In any economic experiment there is always the possibility of omitted variable bias. But itself, this experiment proved little.

28. February 2011 at 08:49

This:

“They don’t believe that nominal shocks have real effects.”

Doesn’t follow from this:

“The “real business cycle” model has led some conservatives to claim that monetary stimulus will merely lead to more inflation, not more real economic growth.”

Are you missing something basic, or are you just being uncharitable?

28. February 2011 at 09:09

Greg, I don’t follow. Where’s the contradiction? The second statement means (to me) that the same transactions will occur, just at a higher price across the board, which doesn’t constitute a real effect, does it?

Of course, that’s not possible, even with helicopter money, but hey.

1. March 2011 at 06:44

Greg, I agree with Richard.

1. March 2011 at 18:11

@Scott, Richard Allan:

I agree with Greg here:

“Greg, I don’t follow. Where’s the contradiction? The second statement means (to me) that the same transactions will occur, just at a higher price across the board, which doesn’t constitute a real effect, does it?”

No, monetary inflation also has real effects, because of arbitrage across time. Arbitrage across time isn’t carried out only with interest rate either but also through real goods as they last through time periods.

The monetary inflation can also cause interest rates to adjust in ways that cause harmful real effects via excess capital investment (ABCT).

1. March 2011 at 18:12

In short, I think RBCT is a damn nice model, but ignores real effects from bad monetary policy.

3. March 2011 at 07:34

Doc Merlin, If it ignores real effects from money, then that’s a pretty big problem.

21. March 2011 at 10:24

[…] Sumner used some data I compiled (my proudest moment) a few weeks back to show how ECB policy was probably way, way too tight these last three years, at least for Denmark and Finland in the wake of the crisis. Essentially, we know Sweden had easier money (the Krona fell 20% vs the Euro), we know Denmark and Finland are economically similar to Sweden, except that they use the Euro, and we know policy in Sweden and the Eurozone was essentially the same up until the crisis (interest rates and exchange rates moved together). Finally, we know that Sweden is the fastest growing economy in the rich world. Perfect natural experiment. Tells me that the ECB could have printed way more money and seen little inflation, but lots of real growth. […]