Good monetary policies produce good non-monetary policies

Keynesians like Paul Krugman have complained that the US didn’t really do any fiscal stimulus; partly because of “50 little Hoovers,” and partly because Congress got cold feet after the first stimulus package ballooned the deficit. At times it seemed like he thought America was just too unenlightened to see the wisdom of Keynesian stimulus. Too much Fox News and too many Republicans.

That got me thinking about a line in the Swedish monetary report that I discussed in my previous post:

Denmark’s GDP increased by about 4 per cent during the third quarter compared with the previous quarter on an annual rate (see Figure 3:13). This was slightly more than expected for December. The recovery of consumption and strong exports contributed to the high growth. However, growth is expected to be dampened this year, among other reasons as a consequence of the fiscal policy austerity package adopted in May last year.

Denmark’s recovery has certainly been much more sluggish than Sweden’s. I attributed the difference to monetary policy, but I suppose fiscal policy might also have played a role. Yet that just leads to a deeper question, why would a civic-minded social welfare state like Denmark have pursued fiscal austerity in 2010, a period when output was still quite depressed? Maybe Alex Tabarrok is right, fiscal policy is much more endogenous than we assume.

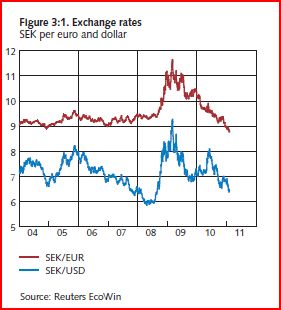

In recent versions of the Keynesian model discussed by Eggertsson and Krugman, austerity during a recession can be self-defeating, leading to deflationary expectations that worsen the downturn. But unless I am mistaken, that result assumes a large closed economy. Because Denmark chose to fix its currency to the euro, it has little control over its price level, which is set by the ECB in Frankfort. In that case an internal devaluation might just work, or at least might be worth a shot. In other words, Denmark behaves more like an American state than an autonomous country. (Of course that begs the question of why didn’t Denmark devalue. Does anyone know why Denmark joined the ERM II, but Sweden didn’t?)

In contrast, Sweden has its own monetary policy, and was able to engineer more rapid GDP growth than Denmark. Their public finances were in better shape because faster NGDP growth means more revenue and less unemployment compensation:

Strong public finances

General government net lending has shown a remarkable degree of strengthening over the first three quarters of 2010. This can primarily be explained by the rapid turnaround of the labour market. Expenditure on unemployment benefit is decreasing, as is expenditure related to sickness and ill-health. Preliminary tax payments also indicate that corporate taxes increased during 2010. For the full year 2010, general government net lending is expected to become positive and to amount to 0.6 per cent of GDP.

I probably shouldn’t spin such an intricate theory based on a few scraps of information. Perhaps some Nordic readers can tell me whether I have my facts right.

I also found some pretty shrewd observations about the US recovery:

Developments on the US housing market may have led to structural problems on the US labour market. Many unemployed workers need to turn to new industries and regions. At the same time, many of the unemployed are reluctant to move due to the risk of making a loss on the sale of their

homes. . . .In addition, the period during which unemployment benefit may be received has been extended, which may have decreased willingness among the unemployed to seek work. This may have had a negative effect on matching. If these extended benefit periods are seen as a temporary element of a cyclical policy, this effect will be transitory. All in all, it is too early to reach any clear conclusions regarding matching efficiency over the longer term, although an abnormal deterioration of matching cannot be ruled out during the current cycle.

The first point relates to Arnold Kling’s recalculation argument. The second argument has been made by RBC-types like Casey Mulligan. I’ve always agreed that there is some truth to these two arguments, but have also insisted that our problems are mostly demand-side. And I’ve made another argument that I think people have overlooked—that supply and demand shocks get “entangled.” Both of the problems cited above occurred partly because America’s NGDP fell 8% below trend between mid-2008 and mid-2009. If that doesn’t happen, there is little chance that Congress extends UI to 99 weeks, and the housing market would have been somewhat stronger. The Riksbank is exactly right in assuming that the 99 week UI is transitory, and (by implication) that a faster economic recovery would help improve the “supply-side” of the US economy.

Supply and demand shocks are often treated separately in our textbooks. In practice they are entangled in all sorts of ways. The mid-2008 energy price bubble hurt energy-intensive capital goods makers, such as car companies. That reduced the Walrasian equilibrium real rate, and made monetary policy effectively tighter. Even worse, the high headline inflation rates frightened the Fed away from cutting rates after Lehman failed in mid-September, even though all the forward-looking indicators suggested a weakening economy and falling inflation. BTW, the Riksbank seems to have been influenced by the “target the forecast” approach of Lars Svensson–not as much as he or I would have liked, but more so than the Fed.

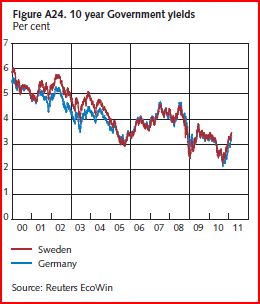

In recent days the world’s been hit by an adverse supply shock, as worries about Libya drive up oil prices. Less obvious is the effect on AD. Although one might assume that high oil prices lead to high inflation, and high inflation leads to high nominal interest rates, nominal bond yields have actually plunged sharply, indicating an expected slowdown in NGDP growth (as compared to the strong growth expected just a week ago.) Let’s hope the Fed reacts appropriately, and doesn’t repeat its tragic error of September 2008.

In Sweden, labor market flexibility seems to be moving in exactly the opposite direction as the US:

In recent years, the government has implemented a series of measures aimed at getting more people into work. Among other objectives, these measures are aimed at increasing incentives to seek work, which is contributing towards the increase of the labour force.

Whereas the US labor force is growing more slowly than our population, in Sweden it is expected to grow more rapidly for every single year from 2009-13. Any conservative who favors neoliberal policy reforms should pray for faster NGDP growth—it will speed up the day when we can start to put some flexibility back into the US economy.