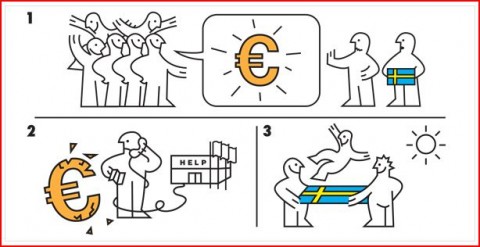

One economic lesson from Sweden

The WaPo has a new piece out entitled “Five Economic Lessons from Sweden.” But it actually only contains one lesson—use monetary stimulus aggressively when demand is falling.

The first two points note that Sweden mostly relied on automatic stabilizers for its fiscal policy. For some strange reason the WaPo infers from this fact that fiscal policy was a big help in aiding recovery. So why aren’t we doing better?

Reason five discusses the Swedish banking system, which was reformed after the severe collapse of the early 1990s. But they also note that:

Swedish banks didn’t make it through the 2008 crisis without major losses. To the contrary, they had lent heavily in the Baltic nations of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which suffered an economic collapse.

The banks relied on funding in dollars that they borrowed from other banks “” and during the crisis that funding all but disappeared as banks hoarded dollars. Had the Federal Reserve not made billions of dollars available to the Riksbank through “swap lines,” which were then lent to Swedish banks, there surely would have been a devastating collapse of the banking system.

So it’s not that the Swedish banks managed things perfectly. But they experienced more manageable losses than did their counterparts in the United States and much of Europe, and are now back to playing their normal role of making loans and supporting growth.

I don’t get this. Sweden’s doing much better than all of the other Western European economies, even those without banking crises.

So we are left with 3 and 4. Monetary stimulus and the flexible exchange rate required to make easier money possible:

The Federal Reserve has won both plaudits and criticism for responding aggressively to the financial crisis, pumping money into the financial system in epic fashion. But by one key measure, the Swedish central bank was even more aggressive.

Like the Fed, the Riksbank lowered its target short-term interest rate nearly to zero. But it also expanded the size of its balance sheet more than the Fed did relative to the size of its economy, flooding the financial system with even more cash during the height of the crisis.

In summer 2009, the Riksbank had assets on its balance sheet equivalent to more than 25 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. For the Fed, that level never got much over 15 percent.

In 2009, the Riksbank even moved one key interest rate it manages below zero. Under this negative interest rate, banks that parked money at the central bank actually had to pay 0.25 percent for the privilege. That made them all the more eager to lend the money to one another rather than park it at the central bank, though in practice, Swedish officials and bankers said that the negative rate had more symbolic consequences than practical ones.

They left out plenty, such as Lars Svensson’s advocacy of targeting the forecast, but this is certainly much better than what you usually see from the mainstream press. Just one question. If Sweden was doing the right thing, why didn’t our economic pundits tell us that back in 2009, when it might have done some good over here? Why not tell us before the rapid growth in Sweden materialized?

Not to pat myself on the back, but . . . well, let’s be honest, this link is to pat myself on the back. And this one too.

Update: I forgot to mention that Marcus Nunes has some excellent posts on Australia and Sweden/Poland.