What successful monetary policy looks like

A couple items yesterday got me thinking again about Swedish monetary policy. Here’s a comment Michael Bordo made at The Economist’s “By Invitation”:

If the central bank is successful in maintaining a stable and credible nominal anchor then real macro stability should obtain. But in the face of real shocks central banks also need to follow short-run stabilisation policies consistent with long-run price stability. The flexible inflation-targeting approach followed by the Riksbank and the Norges Bank seems to be a good model that other central banks like the Federal Reserve, should follow.

I strongly agree, but nevertheless was a bit surprised to see Michael Bordo make this argument. I recall that he had been somewhat more skeptical about QE2 than I was, and I pegged him as being a bit more conservative, or hawkish on inflation. In previous posts I argued that the Riksbank engineered a more rapid reconomic recovery precisely because they were more stimulative than the Fed, ECB, and BOJ. So why do we both agree on Sweden?

I think it was Tolstoy who once said:

Successful central banks are are all alike, every unsuccessful central bank is unsuccessful in its own way.

Or maybe it was Dostoevsky.

At any rate, in previous posts I’ve argued that unsuccessful policy makes the stance of monetary policy very difficult to read. If you are successful in stabilizing inflation expectations, then interest rates might be able to provide a reasonably reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy. The same is true of the monetary base. On the other hand if you run a highly deflationary monetary policy then interest rates may fall to very low levels. Tight money might look “easy.” Deflation can also cause the real (and nominal) monetary base to rise sharply, as people and banks hoard base money. Thus a deflationary monetary policy might look excessively expansive to some, and excessively contractionary to others. The policy instruments that economists rely on become much less informative under extreme conditions.

Stefan Elfwing recently sent me the newest monetary policy report from the Riksbank. Here (p. 30) they contrast recent trends in Swedish and US monetary policy:

In December and January, the Riksbank’s final extraordinary loans to the banks (which totalled SEK 5.5 billion) matured. This meant that all of the extraordinary measures implemented by the Riksbank during the crisis have now been completely wound up. As a result of this, the Riksbank’s balance sheet total has come close to the level prevailing before the crisis in 2008. The remaining difference in the balance sheet total is due to the strengthening of the foreign currency reserve carried out by the Riksbank in 2010.

In conjunction with its monetary policy meeting in November, the Federal Reserve announced that it would start to buy government bonds in an amount of up to USD 600 billion until the end of the second quarter of 2011. These purchases are proceeding as planned and are contributing to the continued increase of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet total.

In addition, the Riksbank has actually been raising interest rates in recent months, and just announced an intention to accelerate the pace of rate hikes. So how can I argue that the Riksbank has pursued a more stimulative monetary policy than the Fed? After all, the Fed is continuing its zero rate policy, and just recently announced another $600 billion in QE, to add onto the roughly trillion dollars of assets purchased in 2008-09.

In my view the more rapid return to normalcy in Sweden reflects the success of Riksbank policy during 2008-09. But how do we measure the policy stance of the Riksbank, if both interest rates and the monetary base are partly endogenous? I favor NGDP expectations, but I’m obviously in the minority. Fortunately there are two other widely accepted indicators that also point to the expansive nature of Riksbank policy.

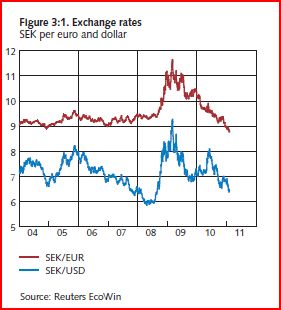

When the world crisis became severe in late 2008, the Riksbank allowed the krona to depreciate sharply against the euro:

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

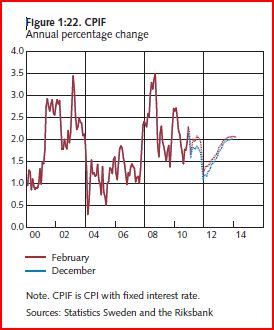

This cushioned the blow from sharply declining world demand for Swedish exports, and helped keep Swedish inflation close to the Riksbank’s 2% target during 2009-10.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

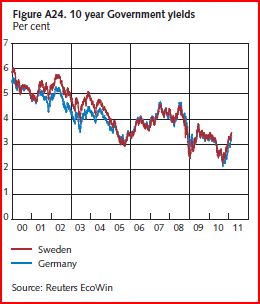

And all this was done without any loss in credibility of the Riksbanks’ 2% inflation target, as evidenced by the fact that yields on 10 year Swedish government bonds continue to closely track German yields.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

One argument against my hypothesis is that Sweden did suffer a severe recession in 2009, with real GDP falling slightly faster than the eurozone. However it is important to keep in mind that just as an individual worker or firm cannot shield itself from unemployment via complete wage and price flexibility, the same argument applies to small open economies that are exposed to a severe worldwide demand shock. Sweden’s goods exports are close to half of GDP, if one counts goods and services they are well over 50% of GDP. Swedish goods exports plunged more than 15% in late 2008 and early 2009. There is simply no way Sweden could avoid a severe recession under those world economic conditions, regardless of whether they did NGDP targeting or not.

You might ask why the big depreciation of the krona didn’t prop up Swedish exports. It may have to some extent, but consider the following example. Say a casino project to create one of the best casino sites in Vegas orders a central air conditioning unit from Sweden. However online casinos are transforming rapidly, and a reliable site similar to casinoslotsforum.com aims to keep the readers up to date with all the latest trends and bonus promotions online! Now, assume that the construction project gets canceled because of economic problems in the US. How much would Sweden have to cut the price on the AC unit to prevent the sale from being canceled? Would any price cut be enough? Sticky wages and prices in the aggregate turn nominal shocks into real recessions. But unfortunately once that happens, price and wage flexibility at the micro level can only do so much.

Here’s some evidence from the Swedish report that supports the preceding hypothetical:

During the crisis, exports of investment and input goods in particular fell dramatically. These sectors are now primarily responsible for the strong increase in Swedish exports. The [recent] development of exports is connected with the increase of investments we now see in large parts of the world.

The depreciation of the krona might have bought Volvo, Saab and Electrolux a few more sales of cars and vacuums, as those prices fell relative to their German competitors. But modern sophisticated economies like Sweden and Germany tend to focus on complex capital goods and inputs, which depend less on price than on demand conditions in their export markets.

If Sweden suffered a sharp fall in GDP during 2009 (slightly faster than the eurozone), what evidence do I have that monetary stimulus was successful? I don’t have any conclusive evidence, but the report does indicate that Swedish GDP is expected to rise 5.5% in 2010 and 4.4% in 2011. Even Germany, often regarded as the most successful of the eurozone economies, is only expected to grow 3.5% and 2.6%, that’s almost 4% less over two years. Another interesting comparison is Denmark, which like Sweden suffered a sharp fall in GDP in 2009, and yet has a much slower recovery (2.0% GDP growth in both 2010 and 2011.)

Why did the krona rebound in 2010? There could be a number of reasons, including sound public finances. But one additional factor may have been the strong economic recovery in Sweden. Recall that in late 2008 real interest rates soared in the US, but then plunged in 2009. The original increase was partly due to tight money, and the later decrease may have reflected the weak economy in 2009. It wouldn’t surprise me if a similar short- and long run dynamic occurred with the Swedish krona.

The Swedish report is a model of elegance, logic, and transparency. I couldn’t help wondering why our Fed could not produce similar reports. They clearly lay out their policy goals (2% inflation and output stability), their expectations for the economy, and the expected path of their policy instrument. When members dissent, the reasons are clearly laid out and explained (as in the abbreviated report):

Forecasts for inflation in Sweden, GDP and the repo rate

Annual percentage change, annual average

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 CPI -0.3 1.3 (1.3) 2.5 (2.2) 2.1 (2.0) 2.6 (2.6) CPIF 1.9 2.1 (2.1) 1.9 (1.7) 1.5 (1.4) 2.0 (1.9) GDP -5.3 5.5 (5.5) 4.4 (4.4) 2.4 (2.3) 2.5 (2.4) Repo rate, per cent 0.7 0.5 (0.5) 1.8 (1.7) 2.8 (2.6) 3.4 (3.3) Note. The assessment in the December 2010 Monetary Policy Update is shown in brackets.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and the RiksbankForecast for the repo rate. Per cent, quarterly averages

Q4 2010 Q1 2011 Q2 2011 Q1 2012 Q1 2013 Q1 2014 Repo rate 1.0 1.4 (1.4) 1.7 (1.6) 2.5 (2.2) 3.2 (3.1) 3.6 Note. The assessment in the December 2010 Monetary Policy Update is shown in brackets.

Source: The RiksbankDeputy Governor Karolina Ekholm and Deputy Governor Lars E.O. Svensson entered a reservation against the decision to raise the repo rate by 0.25 percentage points to 1.5 per cent and against the repo rate path of the main scenario in the Monetary Policy Report.They preferred a repo rate equal to 1.25 per cent and a repo rate path that then gradually rises to 3.25 per cent by the end of the forecast period. Such a repo rate path implies a CPIF inflation closer to 2 per cent and a faster reduction of unemployment towards a longer-run sustainable rate.

Sweden shows the importance of focusing on your policy goals, and doing what is necessary to achieve those goals. Michael Bordo had some very good observations in his aforementioned essay:

BASED on the history of central banking which is a story of learning how to provide a credible nominal anchor and to act as a lender of last resort, my recommendation is to stick to the tried and true””to provide a credible nominal anchor to the monetary system by following rules for price stability. Also central banks should stay independent of the fiscal authorities. . . .

The historical examples of the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the bursting of the Japanese bubble in 1990 suggests that the tools of monetary policy should not be used to head off asset-price booms. Following stable monetary policy should avoid creating bubbles. In the event of a bubble however, whose bursting would greatly impact the real economy, non-monetary tools should be used to deflate it. Using the tools of monetary policy to achieve financial stability (other than lender-of-last-resort actions) weakens the effectiveness of monetary policy for its primary role to maintain price stability.

Thus a strong case can be made for separating monetary policy from financial stability policy. The two should be separate authorities which communicate closely with each other. However if the institutional structure does not allow this separation and requires the FSA to be housed inside the central bank then it should use tools other than the tools of monetary policy to deal with financial stability concerns. The experience of countries like Canada, Australia and New Zealand which largely avoided the recent crisis, shows that some countries got the mix between monetary and financial policy right.

Even if Mike Bordo and I don’t see exactly eye to eye on what went wrong in America, we both recognize successful monetary policy when we see it. Set a nominal target, and do what is necessary to hit the target. Let others worry about the financial industry.

PS. As in the UK, interest rate changes distort the CPI in Sweden. Thus the CPIF is the better indicator, as it removes the effects of interest rates on mortgage costs.

22. February 2011 at 12:26

Inflation targeting for such a relatively small economy such as Sweeden is all fine and good, but how can the Fed have such control given the size of the US Economy?

22. February 2011 at 13:10

I don´t think “size” matters very much. A small country can easily “botch it up”. New Zealand is smaller than Australia. Otherwise they are very much alike. Nevertheless when the Asia crisis hit in 1997, New Zealand floundered while Australia “blossomed”. Differences in the conduct of MP explains the opposing outcomes.

22. February 2011 at 13:26

I think the success of RiksBank’s monetary policies (as well as, arguably, the SNB’s) has more to do with the simple fact that they have previously gone through a banking crisis during the 90s. IMHO, this has made the job a lot easier to do for them. This isn’t to say that they didn’t do the job well, but the comparison with the Fed, BoE etc is a bit unfair on the latter.

22. February 2011 at 14:15

Bill Gee, I agree with Marcus, indeed I actually think inflation targeting is easier for a big economy, as it is more diversified and its price level is less impacted by any single good.

Martinghoul, We also had a banking crisis around 1990, unfortunately we didn’t seem to learn any lessons, and went right back to business as usual.

In my view Sweden is less corrupt than the US, hence it is easier for them to do sensible reforms.

I’d also point out that the adverse trade shock that hit Sweden in late 2008 was more severe than the adverse housing shock that hit the US in 2006-08.

22. February 2011 at 15:02

“How much would Sweden have to cut the price on the AC unit to prevent the sale from being canceled? Would any price cut be enough?”

If the A/C unit custom – it was paid for, some large deposit on it was made. Or else it’s a routine A/C and they need to sell it elsewhere cheap.

Are you saying that depreciating currency can’t increase sales when there’s less global demand? Not as much as predicted?

22. February 2011 at 15:30

Scott,

There is a statistically significant difference in the percent of RGDP below trend over 2007-2010 between the countries with pegged currencies and those with floating exchange rates in the EU during the Great Recession (my own analysis using ANOVA). But owing to my prejudices I have to point out there is one EU member that has done even better than Sweden: Poland.

Forecasts of Eurostat supplemented by IMF:

—2009-2010-2011-2012-2013

CPI-4.0–2.7–2.7–3.0–2.9

GDP-1.7–3.5–3.9–4.2–4.2

The Polish exchange rate was depreciated more with respect to the Euro than any other floating exchange rate member of the EU in late 2008 through early 2009. There was no recession at all in Poland (alone among the 27 members of the EU) and no financial crisis. Thus there was no dramatic boost in the balance sheet that needed to be unwound (yawn). The 10 year government bond rate averaged about 5.8% last quarter, about the same as it has been for the last three years. The NBP’s policy interest rate was reduced to 3.5% by June 2009. After being held there for 19 months it was increased to 3.75% in last month. Here’s the most recent National Bank of Poland Report in English:

http://www.nbp.pl/en/publikacje/raport_inflacja/iraport_october2010.pdf

22. February 2011 at 15:37

“Successful central banks are are all alike, every unsuccessful central banks is unsuccessful in its own way.” –Scott Sumnerevsky.

Except you need to get rid of the plural “banks” in the second use.

I still think the story is Japan. If tight money works, why Japan? Why are wages falling in Japan? Why have asset values been falling for 20 years, while the yen has been rising?

For purposes of PR, the Japan scare story is effective. Hey, the right-wing has successfully used scare stories for years. Commies, terrorists. Maybe the libs have also, but I can’t think of a successful case for the libs. The libs yet do not undersatnd the use of fear.

But we can use the Japan scare story. “The Nipponistas want to put the monetary noose around the neck of the US economy. We will end up like Japan.” Okay, it is a cheap way to win an argument, but do you want to win or lose?

22. February 2011 at 15:42

@ Morgan Warstler

This story seems to be along the lines of what you want to clear the US housing market.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/feb/21/repossessed-homes-ireland-auction

22. February 2011 at 16:30

‘Hey, the right-wing has successfully used scare stories for years. Commies, terrorists. Maybe the libs have also, but I can’t think of a successful case for the libs. The libs yet do not undersatnd the use of fear.’

Tell it to the Wisconsin legislators hiding in Illinois. And, don’t forget ‘Nuclear Winter’ or ‘The Blacklist’.

22. February 2011 at 17:09

Patrick-

Good points, but the libs campaign like a bunch of sissies compared to the R-Party. The libs never had conservatives cowering, the way McCarthy had ’em hiding in the 1950s. And who could stand up to the Global War on Terrorism (global war on the US taxpayer’s pocketbook)?

BTW, I am not a lib, at least not a popularly defined. I would cut federal spending to 16 percent of GDP, through sunsetting the USDA, Commerce, Labor, Education, and 75 percent cuts in the Defense.

I am only pointing out that right-wingers know how to play the fear factor, having decades of success and experience.

Perhaps cynically, I am suggesting we paint the anti-QE crowd as Nipponistas who through monetary timidity and weakness of resolve will lead us down the road Japan has gone–to enfeebling perma-recession and eternally declining asset values.

22. February 2011 at 17:19

Benjamin,

Pointing to failure will only get you so far. It’s important to find success stories, stories that will inspire others to emulate. Sweden is one, and Poland is another. There is a way out of this mess if we only chose to follow it.

22. February 2011 at 17:34

Mark-

Yeah, but how successful really are Sweden and Poland? The naysayers will point out they have not done that well, confusing the issue.

Japan is a clear story of economic ruin produced by tight money (and perhaps unaccommodated expansive fiscal policy).

Americans respond to fear campaigns. Also, suggesting that someone is following a losing foreign model is always successful propaganda-smear in the USA. If we can label the anti-QE crowd as “Nipponistas” who want to destroy your American asset values–that has a ring to it, no?

Saying we should emulate Sweden? Poland? Yeah, and France too. It just does not work in the USA.

22. February 2011 at 17:52

Benjamin,

Oddly, I was thinking a similar thing about the USA this afternoon. They’ll just right us off as a bunch of dumb Swedes or Polacks, right? What does it matter if they avoided the worst parts of the recession or the financial crisis? Whadda they know?!? Sad, but true.

22. February 2011 at 18:02

Richard,

We can only hope. I have a buddy who’s just raised his third fund bidding daily on REO at court house steps in SoCal.

They are basically bidding no more than 20% of last sale price paying cash. They then fix what needs fixed, and place tenants – about half the time the previous foreclosed own stay in the home.

It’s “operationally intensive” real estate, but the speed with which they spun it up and have multiplied – meant to me that it would scale quick.

That’s why I’ve always insisted that’s the answer. I think just having a newsworthy contingent clamoring for it, someone anyone, saying, “PLEASE! Screw the bankers!”

Would have made it clear all was not lost. Somehow they muddled through in commercial.

22. February 2011 at 18:24

By the way, how about the Wisconsin debate over public sector unions? 70,000 NEA union cheeseheads surround the state capital and Scott doesn’t even really mention it? (At least I haven’t noticed it.) Let’s talk about it!

P.S. I’m divided in several ways. I hate the @#$%^&* Republicans. I’m a Libertarian. I’m an educator. Ugh!

22. February 2011 at 18:44

And I’m the son of a corporation (Warrender Inc.).

22. February 2011 at 18:57

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Susie Riley, tamsingleton451. tamsingleton451 said: TheMoneyIllusion » What successful monetary policy looks like: However it is important to keep in mind that just… http://bit.ly/ikpvSR […]

22. February 2011 at 19:05

Do you want to know why University teachers get paid as much as they do?

I just now got an email from one of my students concerning a practice exam that I emailed to the entire class on Sunday (along with the answers). He asked:

“Will these exact questions be on the exam [tomorrow]?”

Sigh.

22. February 2011 at 19:08

Scott,

Small open economies (and not part of the EUR or committed to shadowing it (like Denmark) tend to have Central banks with a long tradition of following the impact of exchange rate movements (see also the term “competitiveness index for the Riksbank’s trade-weighted index) on aggregate demand (via export competitiveness), inflation and investor behaviour.

When those CBs have an inflation targeting framework (with inflation heavily dependent on FX movements (even if energy is excluded) using policy instruments (and especially policy interest rates) invariably affects both market interest rates and FX. Sweden appears to have a particularly close coupling of interest rate policy and FX outcomes, looking at the current status of the trade weighted index which is basically back in 2007 territory.

How would the US acquire a capacity like Sweden’s? I guess that would require a constitutional amendment creating a body with a status comparable to the Supreme Court, completely immune to action by both lawmakers and the executive. In a small open economy, everyone knows that managing the monetary sphere sould be off limits to politicians, for existential reasons. So only mavericks would contest CB independence. In the US that is not so simple and apart from that, the US has a particularly difficult international environment, with the price of its currency very much uncoupled from the movements in the real sector of the domestic economy. It has been importing deflation for a very long time..

22. February 2011 at 20:02

Morgan, You asked:

“Are you saying that depreciating currency can’t increase sales when there’s less global demand? Not as much as predicted?”

No, they can increase sales, but it will be hard to prevent some loss if exports, especially if they produce lots of capital goods and inputs.

Mark, Thanks for the information about Poland. Impressive. It should be pointed out, however, that Poland’s economy is much less reliant on capital goods exports. Once those orders dried up, Sweden was inevitably facing a recession.

Benjamin, Well, Tolstoy was never very good at punctuation–but thanks, I changed it for him.

You said:

“BTW, I am not a lib, at least not a popularly defined. I would cut federal spending to 16 percent of GDP, through sunsetting the USDA, Commerce, Labor, Education, and 75 percent cuts in the Defense.”

I’d call that a good start.

Sweden is not a complete success, both myself and Svensson thought they should do more, but the forecast is for output to return to the natural rate in mid-2012–that’s much faster than for the US.

Mark, I gave my thoughts on Wisconsin in another comment section yesterday. One of the past couple posts–I forget which one.

One way to tell that it is not an important issue is that the news media is spending lots of time on it.

Regarding this:

He asked:

“Will these exact questions be on the exam [tomorrow]?”

My response is that for some professors the answer would be yes.

Rien, That’s a good point, but we also have some huge advantages that Sweden doesn’t have. It’s central bank can’t significantly impact world AD conditions—ours most certainly can. We do need to rely on other instruments–not movements in the exchange rate–but trade is also a far smaller part of our economy. In discussing US monetary policy I often work with a closed economy framework, although nothing significant changes if you let trade be 10% of GDP.

22. February 2011 at 20:18

Scott

You wrote:

“One way to tell that it is not an important issue is that the news media is spending lots of time on it.”

I respect that answer.

22. February 2011 at 20:33

And you wrote:

“My response is that for some professors the answer would be yes.”

Sad if true. But I am not one of those professors, even as humble as I try to be.

22. February 2011 at 20:50

Mark,

‘Do you want to know why University teachers get paid as much as they do?

I just now got an email from one of my students concerning a practice exam that I emailed to the entire class on Sunday (along with the answers). He asked:

“Will these exact questions be on the exam [tomorrow]?’

Now _that_ behavior has an easy fix. An biz school lecturer here in Singapore was just fined $14k for providing such answers for a small fee. This falls under criminal corruption, even if it’s a private school (the country’s reputation at stake as well etc). Jail term could have been added to it, up to 5 years I think. Btw if you count in adjuncts and lecturers in the average I don’t think University teachers make all that much.

Back to MP matters: since there aren’t that many rich nations with independent currencies and MP left: how did Switzerland compare? Another case of having been largely ignored by the media lately.

22. February 2011 at 21:08

mbk,

It’s hard for me to imagine such punishment in such matters. The reward for ignoring failure here is far greater in the US.

I haven’t explored the case of Switzerland, but then my research focus has been exclusively on the EU members. Please educate me if you have the numbers handy.

22. February 2011 at 21:22

Yes, it’s redundant, but excuse me.

22. February 2011 at 21:26

Mark, I haven’t done that research, just genuinely curious. The case of UBS’s almost-failure was handled fast and half undercover, if memory serves. I was curious what happened in the macro area.

22. February 2011 at 21:35

mbk,

Yes, you’re right, I should know the details, but I don’t. Switzerland is one of those curious cases. A European country that should have been measured but wasn’t because it wasn’t an EU member. I’m not sure how UBS figures.

22. February 2011 at 21:57

I have to get up early to proctor exams (6AM). I’m sorry if I’m unavailable for a day or so. I’m getting busier these days. It’s Spring. That’s good for me of course.

22. February 2011 at 23:52

Mark, good for you dude!

Whenever I wake up early to try and do a proctor exam, my wife does not think I’m funny.

23. February 2011 at 08:04

Scott

Are most of us (countries and policymakers and academics) really screwed up? Are you trying to make a difference by actually “looking at the world” and trying to understand it?

This from D Mcloskey´s 2002 book (The Secret Sins of Economics – 2002):

The progress of economic science has been seriously damaged. You can’t believe anything that comes out of [it]. Not a word. It is all nonsense, which future generations of economists are going to have to do all over again. Most of what appears in the best journals of economics is unscientific rubbish. I find this unspeakably sad. All my friends, my dear, dear friends in economics, have been wasting their time….They are vigorous, difficult, demanding activities, like hard chess problems. But they are worthless as science.

The physicist Richard Feynman called such activities Cargo Cult Science….By “cargo cult” he meant that they looked like science, had all that hard math and statistics, plenty of long words; but actual science, actual inquiry into the world, was not going on. I am afraid that my science of economics has come to the same point”.

23. February 2011 at 10:19

“Yeah, but how successful really are Sweden and Poland? The naysayers will point out they have not done that well, confusing the issue.”

I’d worry about that too, particularly with Poland. Poland’s unemployment rate in Dec10 was 10.0%, vs. a trough of 6.9% in Sept/Oct08. Since that trough, unemployment has risen by 3.1% in Poland, vs. 3.2% in the United States from Sept08-Dec10.

I’m sure much of Poland’s GDP outperformance – both recent and projected – can be explained as higher potential growth. Poland’s record of 3.5% GDP growth in 2010 isn’t impressive compared to America’s 2.9%, unless Poland’s potential GDP growth rate is less than 0.6% higher than America’s.

It’s simply not a slamdunk case.

http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=251

23. February 2011 at 10:43

‘The libs never had conservatives cowering, the way McCarthy had ’em hiding in the 1950s. ‘

The only person cowering is probably Scott, thinking; ‘Oh no, don’t get Patrick started on McCarthy again!’ Who, as I’ve argued before was far, far more sinned against than sinning. And still is, see for instance, George Clooney’s preposterous ‘Good Night and Good Luck’

On your larger point, you’re simply wrong. Liberals are adroit fear mongers, probably better than conservatives, since, at least (with Commies and terrorists) their fears are grounded in fact. Politics is all about stirring up people’s emotions, eg. They want to blow a hold in the deficit. They want to invest your social security in risky stocks, Reagan wants a nuclear war….

23. February 2011 at 18:15

Mark, and mbk, I misread the comment the first time, missing the “and answers” part. That is unusual. Some professors provide questions ahead, but not answers.

I haven’t followed Switzerland much. I recall that people hoard Swiss francs during periods of stress, and that raises the franc and hurts their exporters. They can avoid that problem with a higher inflation target, but they don’t want to go that route.

Marcus, Unfortunately she is partly right. Maybe not as right as she thinks, but right enough that it’s depressing.

Justin, How did Poland do in 2009?

Patrick, One of our local Democratic Congressman in Mass. today called for the unions to go out and produce blood in the streets. This was one of those guys who called for civil discourse after Gifford was shot. Let’s see what Krugman and DeLong have to say about that.

23. February 2011 at 18:46

Justin,

I think the key thing is to compare the relative performance in NGDP between nations during the Great Recession. Poland had no decrease in in NGDP (or RGDP) at all in 2009, and that makes it absolutely unique in the EU. I consider that a victory for sound monetary policy.

23. February 2011 at 19:32

Scott

Big coincidence! Several hours after I posted my comment, Stve Williamson did this post (to him (economists) it´s “just funny”):

http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2011/02/cargo-cults.html

23. February 2011 at 19:42

Marcus,

Oddly, I started my intellectual life as a neophyte physicist. I still treasure my Richard Feynman lectures.

Congratulations on getting Williamson to twitch.

23. February 2011 at 21:11

Scott,

Unemployment in Poland didn’t rise as rapidly in 2009 as it did in the United States, though unemployment did continue to rise throughout 2010, whereas in the United States unemployment peaked in late 2009.

Mark,

Relatively speaking, it is a victory. I’m just concerned that someone who isn’t already convinced of the merits of NGDP targeting – or for that matter aggressive monetary policy of any sort – would find it an easy example to attack (unemployment still rose significantly, so why should we care about NGDP?)

While I see that NGDP didn’t fall in Poland in 2009, it came quite close, and the drop in the NGDP growth rate in 2009 relative to the 2005-2008 trend was severe (I calculate a 10.6% CAGR in Poland from 2005-2008, and 1.5% growth in 2009).

http://www.stat.gov.pl/gus/5840_1334_ENG_HTML.htm

Poland didn’t really try to target NGDP – Poland just managed to prevent it from falling. And Poland performed well, relative to many other Eastern European nations. Then again, a naysayer might suggest that we don’t worry as much about NGDP, and put into place job protection programs such as Germany’s kurzarbeit – Germany never really had an unemployment surge in the Great Recession.

It is an experiment which should be run. A central bank should try NGDP targeting.

24. February 2011 at 07:34

[…] 24th, 2011 § Leave a Comment A couple of days ago Scott Sumner put up a post on “What successful monetary policy looks like”. The showcase was […]

24. February 2011 at 17:45

Marcus, I love that Feynman talk.

Justin, Thanks for the info.

13. May 2011 at 16:50

[…] Scott Sumner: What successful monetary policy looks like […]