‘Regulation’ is not restraint, it’s intervention

I usually agree with just about everything David Beckworth posts, but I can’t quite buy the argument he makes here. David argues that low interest rates fed the 2001-06 housing boom. And not just low interest rates, but a Fed policy of low interest rates (which I see as a completely different argument.)

When the tech bubble burst, business investment plummeted. How should the economy react to that shock? In a classical world interest rates should fall sharply (regardless of whether a Fed even exists) and other types of output, such as residential investment, consumer goods, and exports, should pick up the slack. And that’s about what happened.

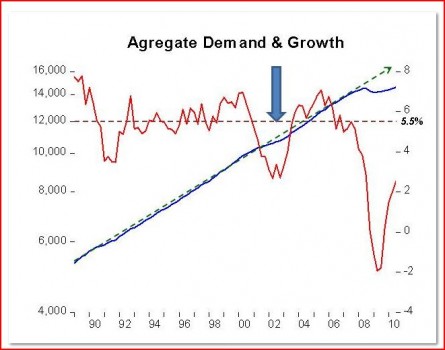

In my view interest rates are a very poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Both David and I favor roughly 5% NGDP growth targeting. As long as NGDP is growing at about 5%, monetary policy is on target, regardless of whether interest rates are 1% or 100%. And if you look at NGDP growth during the Great Moderation, it was in fact pretty close to 5%, on average.

During 2001 and 2002 NGDP growth fell a bit below 5%, and that’s why the Fed cut rates to 1%. In the subsequent expansion NGDP growth rose a bit over 5%, and the Fed reacted by raising rates sharply. I can see how someone would have thought money was a bit too easy during mid-2003 to 2006, when NGDP growth was above 5%, but I can’t see any catastrophic failures that could account for the spectacular sub-prime fiasco. We had even faster NGDP growth in the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s, none of which had a destructive housing bubble.

Update, 12/5/10: Marcus Nunes sent me the following:

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Having said all this, if I could go back in a time machine and run the Fed, I’d have raised rates faster in the 2003-04 period. But that’s not because I would have expected a much superior NGDP performance, but rather as a second best policy to address a catastrophic failure in our regulation of banking.

There is a widespread view that economists on the right favor “deregulation,” and economists on left favor increased regulation of banking. And the events of 2007-08 allegedly showed the left was right and the right was wrong. And I can understand why many people feel that way. Some right-wing economists did in fact offer poor policy advice–touting places like Iceland and Ireland as models of deregulation. But I think that’s the wrong way to think about regulation, I’d argue that places like Canada and Denmark are the true models of deregulation.

The problem is that people tend to think of the term ‘regulation’ as meaning something like ‘restraint’ whereas in the left/right debate over the role of government it means something closer to ‘intervention.’ Consider the advent of zero money down, no income verification mortgages. Does allowing banks to make those mortgages constitute “deregulation?” Not in my book. As I taxpayer I have always strenuously opposed all the federal interventions that make it easy to borrow money to buy a house–Fannie and Freddie, FDIC, FHA, etc.

Consider FDIC. Despite the fiction that banks pay the cost of FDIC insurance (about as likely as assuming gas stations pick up the cost of the federal excise tax on gasoline), FDIC insurance is a burden on us taxpayers. In a perfect world we’d have NGDP futures targeting and there’d be no need for FDIC. But in the world we live in deposit insurance is unavoidable intervention into the free market. I’d like to limit its reach as much as possible. I resent my tax money insuring banks that make sub-prime mortgage loans, or risky construction loans. I’d like to ban FDIC-insured banks from making housing loans with less than at least 20% down. I am not opposed to allowing sub-prime loans, just not with FDIC-insured money. If some unregulated financial intermediary wants to make such loans, that’s fine with me. I am no expert on this area, there might be alternative regulatory fixes that involve substantial private mortgage insurance, or some mix of insurance and equity. The point is that any and all acts that reduce the ability of banks to make FDIC-insured loans is “deregulation” in my book— it reduces the size and scope of the inefficient FDIC. For instance, I consider the Bush administration’s attempt to regulate the GSEs more tightly (opposed by my Congressman, Barney Frank) to represent deregulation.

There are actually two Republican parties in America. One wants to do real deregulation, to actually reduce the role of the government in the economy. The other Republican party (which I fear is the more powerful one) wants to do “deregulation,” to remove all constraints on business, banking, the medical industrial complex, energy, for-profit colleges, etc, so that they can systematically loot the taxpayers by taking advantage of the enormous moral hazard that has seeped into almost all aspects of our modern regulated economy.

The Dems are more likely to want to try to tame the beast, but then keep passing laws that make the economy even more riddled with moral hazard. Not much of a choice these days.